What Makes Materials Authentic? PART 1

Using a Broader Definition to Understand the Value of Children’s Stories

We all recognize the value of integrating authentic materials into the classroom. They can and should form the backbone of our curriculum for teaching Chinese language, making the language real by bridging the gap between the sheltered environment of the classroom and language as it's used "in the wild."

One of the most enjoyable parts of teaching for me is searching out these materials and figuring out how to use them effectively in the classroom. To give a few examples, this past week, Chinese III students started reading a recent news article entitled "An iPhone 6 That Was Purchased in the Morning Was Stolen in the Afternoon" (上午买的 iPhone6下午就被偷了, Shàngwǔ mǎi de iPhone6 xiàwǔ jiù bèi tōule). This article, about a store owner whose iPhone 6 was stolen by two men posing as customers, introduces students to the passive voice particle 被 bèi).

Last month, Chinese II students used iPads to search for and discuss clothes they like on Taobao.com, and Chinese I students learned the names of class subjects by studying a photograph of a class schedule that I spotted taped to a classroom door at our partner school. All of these materials fit our usual understanding of "authentic," which we roughly define as materials "created by and for native speakers."

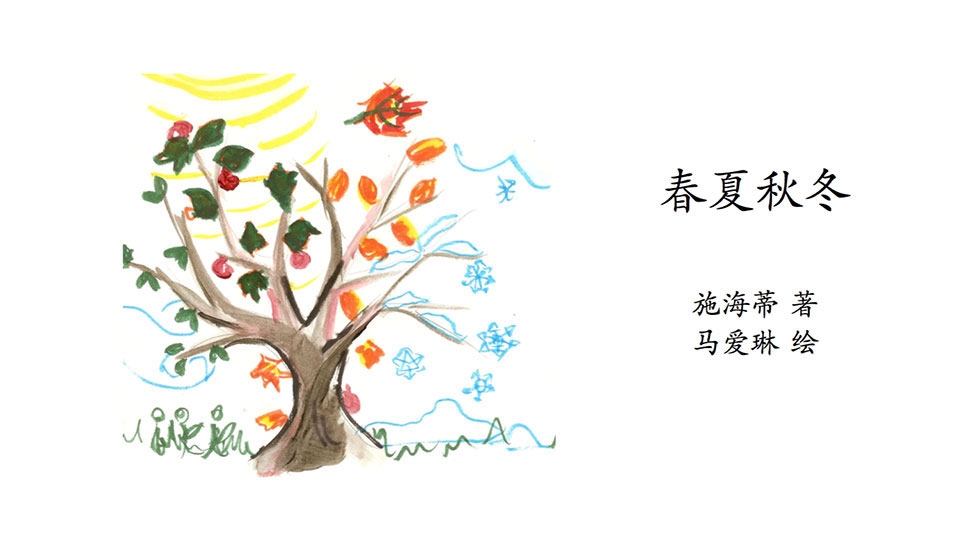

In addition to working with these types of authentic materials, I have also begun writing children's stories and using them with my students. My inspiration for this project comes from three leaders in our field, Cynthia Ning, Helena Curtain, and Myriam Met, who have presented on some aspect of storytelling at the National Chinese Language Conference in recent years.

These children's stories don't meet the traditional definition of authentic. They are not written by or for native speakers. Nonetheless, the stories feel authentic to me, and student feedback and my own observations have led me to believe that these stories promote learning for my students in many ways. Thinking about this made me question our collective understanding of the term "authentic" and wonder whether we might extend the meaning of this word as it relates to world language teaching.

I began reading Chinese stories to my now-fourteen-year-old son when he was an infant, and I read to him almost every night for about thirteen years. We also listened to many hours of stories on tape together, attended Chinese language story hours at a library in Seattle, and made up stories for each other.

Over the years of parenting a bilingual child, I slowly absorbed the rhythm and cadence of Chinese children's stories and came to love the feel of the language as it’s used in this context. After attending the sessions on storytelling at the NCLC, I started thinking about the fact that unless students start learning Chinese in an immersion setting as a young child or hear Chinese in the home, they miss out on this warm and cozy side of the language.

Children's stories provide a window into an area of Chinese that other authentic materials do not. The materials we typically provide to our middle and high school students are intended to help them learn how to accomplish practical linguistic tasks, such as ordering in a restaurant or asking directions.

To teach these types of skills to beginning students, we ask them to extract bits of information from packaging, signage, advertisements, or business cards, for example, or ask them to listen for the key words in a media broadcast. These are worthy activities and we should indeed make them a focus of our teaching. What these types of authentic materials may not impart, however, is the rhythm, phrasing, and musicality of Chinese. Children’s stories are one of the primary means by which this cultural and linguistic heritage is passed down from generation to generation.

In cultures around the world, adults and children bond over stories. When we read stories to our students in class, we give them an opportunity to share in this tradition. In some small way, they are able to experience the Chinese language as they would have had they grown up in Chinese-speaking homes. I would also wager that reading stories might help our students form positive associations with Chinese, especially if they were read to in their native language when they were young and have fond memories of that experience.

From the perspective of language proficiency, I also hope that reading stories will improve my student's reading and writing skills. Children's stories, with their repetition, engaging content, and pictures, provide ample support to help students infer the meaning of new language items. Furthermore, students can use the vocabulary, sentence structures, and cohesive devices in children's story in any form of writing.

Come back next month to check out how Heidi Steele creates her own stories to promote authentic learning experience for her students.