What Makes Materials Authentic? PART 2

Writing and Using Children’s Stories in the Classroom

In Part I of this article, Heidi Steele proposed an expansion of the definition of "authentic" when teaching Chinese language, and explained why. Below, in Part II of her article, Heidi provides examples from her own curriculum on how she has accomplished this.

In using children's stories to teach Chinese language, we can use stories that are written by native speakers for Chinese children, and sometimes I do. But often it's hard to find just the right story for the right occasion at the right level of difficulty among those that have already been published, and writing my own stories allows me accomplish several things:

In using children's stories to teach Chinese language, we can use stories that are written by native speakers for Chinese children, and sometimes I do. But often it's hard to find just the right story for the right occasion at the right level of difficulty among those that have already been published, and writing my own stories allows me accomplish several things:

- Focus the stories around particular themes that align with my curriculum (weather, family, shopping, hobbies, and so on).

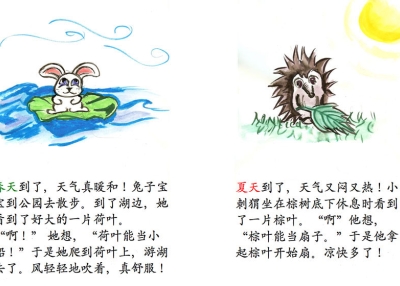

- Involve students in the creative process by having them volunteer to do the illustrations. When a student embarks on creating a story with me, I tell him or her what the story will be and roughly what illustrations I think the story needs, and then I give the student complete freedom to create images using whatever materials and artistic style they like. Stories that are illustrated by students feel authentic, and they are, using one of the New Oxford English Dictionary's definitions: made or done in the traditional or original way.

- I can share certain values through the stories, such as inclusion and acceptance of diversity, without being pedantic. For example, the various families that appear in a story for Chinese I students include single-parent families, multi-racial families, and families with step-parents.

Another reason that my stories feel authentic is that my primary goal is to write an engaging story that can stand on its own in the storytelling tradition. I don’t go out of my way to use words that the students have learned in the lesson, nor do I shy away from using vocabulary and constructions that they have never seen before. My intention is to give my students a feel for the beauty and cadence of Chinese, rather than use the story as a structure in which to cram a particular set of vocabulary and sentence structures.

I am still experimenting with various ways to work with the stories in class, but the following method has worked well thus far:

-

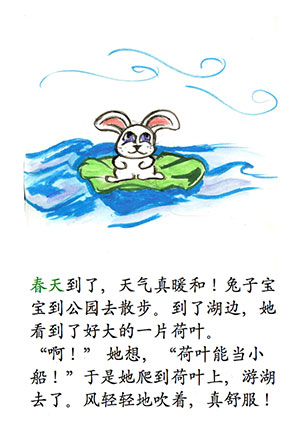

.jpg) I print enough color copies of the stories that I have one for every two to four students. After laminating the stories, I bind them by simply hole punching the spines and tying them with yarn.

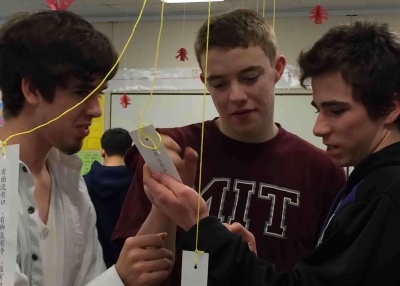

I print enough color copies of the stories that I have one for every two to four students. After laminating the stories, I bind them by simply hole punching the spines and tying them with yarn. - I pass the books out to small groups, and each group either reads the entire book together or is responsible for reading a certain set of pages depending on the story's length and difficulty. They can use dictionaries to look up words they don't know or ask me, but they must speak only in Chinese. Prior to this step, I could read the entire book to them, explaining the meanings of new words and structures along the way, but I like giving students the opportunity to explore the text by themselves. It makes the process more of an adventure, and they enjoy the challenge of figuring out the story on their own.

- If we have divided the book into sections, each group comes up to the front of the class to teach their section to the rest of the group, communicating in Chinese only. I project each page in large text on the screen so that everyone can read together. Each student has a graphic organizer in which they write down all of the words they don't know. The presenting students ask the class questions to make sure they are following along, and they write pinyin and English as needed next to new words.

- After the students have presented the entire text to one another, I dim the lights, ask students to pretend they are little kids, and follow along in their books as I read the story just as I would to a group of Chinese children. It is this final step that pulls everything together for the students. They switch from the hard work of learning new words and constructing the meaning of the text to simply enjoy hearing and feeling the language as it washes over them.

Feedback from students about the stories has been very positive. They enjoy the challenge of working in groups to make sense of challenging text, they like being teachers as well as students, and they love the experience of it all coming together in the end.

While these stories may not fit the traditional definition of authentic material, they do help students improve their reading and writing skills. And more importantly, they serve as a vessel for transmitting a soft and gentle side of the Chinese language, which I believe will deepen students' attachment to the language and their connection to one another.

Interested in using children's stories in your classroom and have questions? Contact Heidi Steele at [email protected].