Trends in Global Engagement for Chinese Language Learners

Strengths and Challenges of School-to-School Partnership Programs

In this article, Heidi Steele, Chinese teacher at Gig Harbor and Peninsula High Schools in the Peninsula School District of Washington State, reflects on sessions she attended at the 2015 National Chinese Language Conference (NCLC) in the partnerships and community engagement strand. She identified and explored the common strengths and challenges of establishing and maintaining meaningful and purposeful school-to-school partnerships, and is excited to see the developments of partnership building in the field.

The theme of this year’s National Chinese Language Conference in Atlanta was “Pathways to Global Engagement.” This phrase can be interpreted in many ways, but certainly one of the most essential aspects of engagement for Chinese language learners is communication with native speakers in the Chinese-speaking world.

The partnerships and community strand provided a quick snapshot of current trends in this area. What was striking about the sessions I attended is that all of the programs featured in the presentations had moved away from practices that were considered standard procedure not long ago. None of them featured “standalone” tourist trips that were not tied into the curriculum and didn’t benefit any students but the few who participated directly. None of them focused solely on seeing the sites. None of them ran trips during which the American students rarely interacted with native speakers. In contrast, all of the sessions highlighted best practices for engaging with students in the target language country in meaningful and enduring ways.

Common Strengths

While the programs I explored are all progressive, they vary widely in their specific focus. Some of them involve travel or study in China, others do not. Some are based in the U.S., and others in China. Some are oriented toward language learning, while others emphasize other areas, such as leadership training and cultural exploration. Regardless of the specific nature of the programs, however, they all share a set of common qualities.

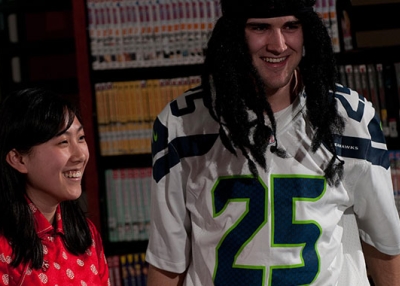

Most fundamentally, all of them are designed to foster communication in authentic contexts. If learning Chinese is the focus, they emphasize acquiring language as a natural outgrowth of interacting with Chinese people in addition to traditional classroom learning. For example, the Chinese Language Institute in Guilin set up their language school to provide ample amounts of time for language learners to simply relax with local college students, playing games, chatting, and exploring the community, all the while speaking in the target language. In fact, in terms of actual time spent, the Chinese Language Institute strives for an equal balance between formal and informal learning environments. And during the capstone China trip for Chinese Immersion students at Hosford Middle School in Portland, OR, students are challenged to use their language skills to accomplish real tasks out in the community, whether it is buying produce in the market or navigating through the city. In programs such as these, the lines between the classroom and the outside world are deliberately blurred to the point that the two learning environments come very close to merging.

When language learning is not the specific purpose of the program, American and Chinese students collaborate around a shared passion or area of study. For example, the New York / Beijing Dance Program of the Americans Promoting Study Abroad (APSA) brings public high school students from New York together with students from the Beijing Dance Academy for an intensive week of study, culminating in a shared performance. In another program, this one developed jointly by the North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics and the Hangzhou Foreign Languages School, students from both schools learn together in a real-time video based class. They share the goals of exploring one another’s cultural practices and pursuing intellectual challenges together, and in this purposeful learning environment they are able to learn about one another in much deeper ways than would be possible otherwise.

All of the programs I learned about at 2015 NCLC pair language and/or cultural exploration with broader goals that serve the needs of young people. APSA designs its programs for public high school students in the U.S. to stress leadership development and exposure to international careers. The Hosford Middle School program is carefully crafted to guide students toward greater independence and resourcefulness at this critical juncture in their emotional and social development. Just as from a linguistic perspective Chinese is a “context based language,” first informing the reader when and where something takes place before describing the event itself, the best partnerships are also carefully crafted to situate language and cultural learning in a broader context, whether it be academic, character, leadership, or career development.

Common Challenges

Even as programs such as these are putting into practice the best ideas in the field of global education, they also face common challenges.

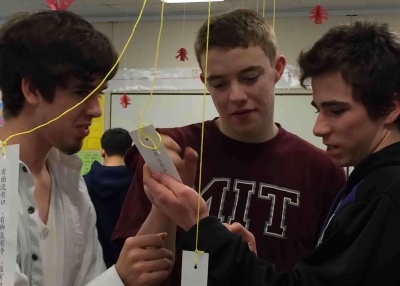

For those institutions seeking to collaborate with partners in China on a year-round basis instead of limiting opportunities for engagement to one-off trips, technology is an on-going issue.

Using real-time video interaction as an example, equipping facilities in partner schools to enable communication between entire classes is a substantial hurdle even if the intent is to communicate in English. Both schools must have both adequate and sustainable funding, as well as trained staff who have the time to research, install, and maintain the proper equipment.

If the intent is to create video-conferencing environments in which the audio is clear enough that our Chinese language students can actually use Chinese to communicate with their peers at their partner school, the bar is even higher. When technological conditions are ideal, a video session can work marvelously well. However, fuzzy audio quality, audio that cuts in and out, and/or a noisy classroom can grind target-language communication to a halt because beginning language learners don’t have the ability to use context to “fill in” the missing words in an audio stream (as they would if they were listening to their native language). In these less-than-ideal situations, the language naturally defaults to English, the stronger of the two non-native languages in most Chinese-American student-to-student interactions. Hopefully the non-native language proficiency will even out over time as Americans place greater emphasis on bilingual education and as world languages are introduced at younger ages in U.S. schools.

Another unavoidable challenge for programs seeking to communicate in real time is the time difference between the U.S. and China. Simply finding a time that fits students’ schedules on both sides, especially for ongoing collaboration, can be very difficult. In my program, we have defaulted to using a blog format as an solution around the time difference issue. The major disadvantage of this approach, however, is that we don’t have the ability to meet “face-to-face” and communicate verbally with one another. Given the advantages of real-time interaction, I expect educators to come up with creative ways of handing the time difference issue that we have not though of yet.

Future Expansion

As more of our students have access to opportunities for genuine global engagement, we can expect their language proficiency to improve as a direct result. When students use their language skills in purposeful ways with native speakers at every stage of their learning process, they develop strong language skills that are embedded in a broad and nuanced understanding of our diverse world. Sessions at 2015 NCLC showcased a number of mature partnerships that are already firmly grounded in these principles. And as the successes of partnerships based on authentic and meaningful communication become more widely known, these types of initiatives are bound to increase in number across the U.S. and China. I look forward to seeing what new partnerships appear on the horizon at next year’s conference.