Strong School-to-School Partnerships: Part II

Differences Are Just as Meaningful as Similarities

Don't miss Part I of this article: "Establishing and Maintaining a Relationship"

Similarities Are Wonderful, but Differences Are Just as Meaningful

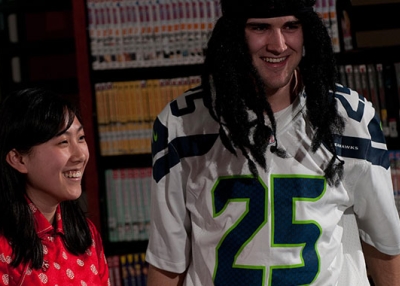

While the homestay exchanges between our American students and our partner school in Mudanjiang are underway, the family focus accentuates not only cultural similarities, but differences as well. These differences, while sometimes uncomfortable, provide a rich opportunity to learn about one another in real life rather than as an academic subject.

One particularly pronounced example of a difference that causes ongoing tension arises when we plan itineraries. The Chinese families prefer to have more all-group activities. In their words, the students are happiest when they are all together. In contrast, the American families prefer more individual unstructured time, when each family arranges activities with their own exchange student. I also prefer to have significant amounts of unstructured family time because that is when the most language learning takes place. As we discussed the problem, we realized that the itineraries on both sides do not need to be mirror images of each other but can instead reflect their respective host cultures. We have concluded that the next time we run the program, the itinerary in the U.S. will include more individual family time, and the Chinese itinerary will include more group activities.

One other difference that provides opportunities for ongoing discussions among students, parents, and teachers is parenting styles. Chinese parents report that before participating in the program, they believed that the American parenting style, with its focus on fostering independence, showed American parents don’t truly love their children. After their own children stayed in American homes and reported back their experiences, however, the Chinese parents came to realize that although the American parenting style differs from the Chinese one, it is also an expression of love. And when our students are in Chinese homes, they experience firsthand the “hands on” approach of many Chinese parents. This style feels claustrophobic to some of our students because they are not used to being micro-managed. As they witness the love between their Chinese student partners and their parents and share their observations with their American parents, however, the American students and parents both develop a deeper appreciation for the Chinese parenting approach.

This past summer one American student came down with an intense intestinal illness while staying with his host family. While he was sick, the student experienced Chinese parenting up close as his host mother, beside herself with concern, tried to convince him to go to the hospital. He adamantly refused, telling his host mother that he knew his own body, and he just needed to sleep and rest. Then, to the mother’s horror, he insisted on dragging a blanket into the bathroom and sleeping on the floor to make it easier to deal with the symptoms of the illness. In his mind, this solution would afford him the greatest degree of comfort as the bug ran its course. To his Chinese host mom, allowing him to sleep on the cold bathroom floor amounted to child abuse. Through this conflict, both the Chinese mother and the American student felt the shared human needs that lay underneath the cultural differences, and they both gained a deep respect for one another’s humanity.

These types of deep learning experiences are only possible in the context of relationships that go beyond superficial politeness and touch on real emotions, and the best way to get to this deeper level of relationship is through extended homestays.

It’s about Real Life

The personal and family-focused nature of this exchange means that potentially sensitive issues are bound to come up for some students and their families on both sides of the partnership, and we often need to work through these situations both before and during the exchange.

As an example, when we begin the process of selecting students, we typically need to reassure at least one or two anxious students that even though they have a “non-standard” family situation (their parents are divorced, they alternate between their parents’ homes, they only have one parent, they have two moms or two dads, and so on) they are still very welcome to participate in the program. As we are making matches, we make sure that these students are matched with accepting host families, and we share as much information as is necessary in advance to ensure that there will be no surprises and ensuing discomfort when the exchange takes place.

Incidences related to romantic relationships and/or exploring sexual preference are also inevitable when running an exchange program for teenagers. If students have not felt the freedom to express themselves within their own families and communities, they may instinctively take the opportunity afforded by being on the other side of the world to experiment with things that are not sanctioned at home. One cultural dynamic that comes into play here is that Chinese teenagers are typically encouraged to push all interest in romantic relationships aside until after high school. At the same time, images of American teenage life in mass media give them the impression that American students are intensely focused on romance and have few limits placed on their behavior. This combination of factors means that Chinese students may, whether consciously or unconsciously, tend to see the exchange program as a chance to explore the world of boyfriends and girlfriends. On the other side, American students don’t necessarily comprehend the intense pressure Chinese students are under to perform well academically, and this lack of awareness can cause them to get involved in seemingly innocuous flirting behavior that in fact has severe negative implications for Chinese students.

Although you can “inoculate” students from getting involved in romance by using signed international travel agreements and a variety of other strategies, these kinds of issues will still likely arise from time to time. When they do, open and clear communication with your Chinese colleagues can help you intervene early and de-escalate situations with tact and a minimum of drama.

The Impact of the Partnership: Everyone Benefits

The partnership we have with Mudanjiang No. 1 High School benefits all of my students, including those who do not participate in the summer exchange.

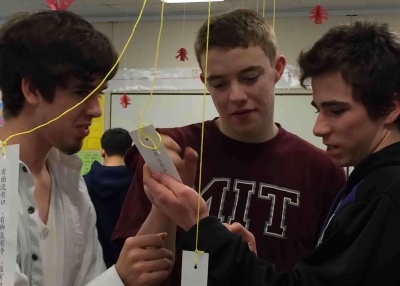

For all Chinese language students, the connection to a partner school gives them a sense of the immediate usefulness of Chinese—they can use what they’re learning to communicate with their peers in China. Classroom learning becomes authentic when I share stories, anecdotes, photographs, new slang terms and cultural trends, and so on, which have arisen from the summer exchange. Students who have participated in the program share their experiences with the other students throughout the school year and in a variety of ways. Furthermore, I continually revise the language and cultural content I teach based on observing what language elements my students need to communicate effectively while in China.

Next Steps

As we move forward, we want to design more collaborative activities that the Mudanjiang students can realistically participate in during the school year given their demanding schedules. We have collaborated in a variety of ways in the past, including an online book club, Skype sessions, a student blog, and student-created videos that introduce slang terms to their peers in the partner school. However, many activities that sound good on paper are not feasible when you look at the detailed picture, including schedules, time differences, and so on. Given these types of challenges, it takes creative brainstorming to come up with ideas that are both meaningful and workable. Nonetheless, with a foundation of trust and a commitment to a long-term relationship, I expect that the connections between our schools will continue to develop in new ways for many years to come.