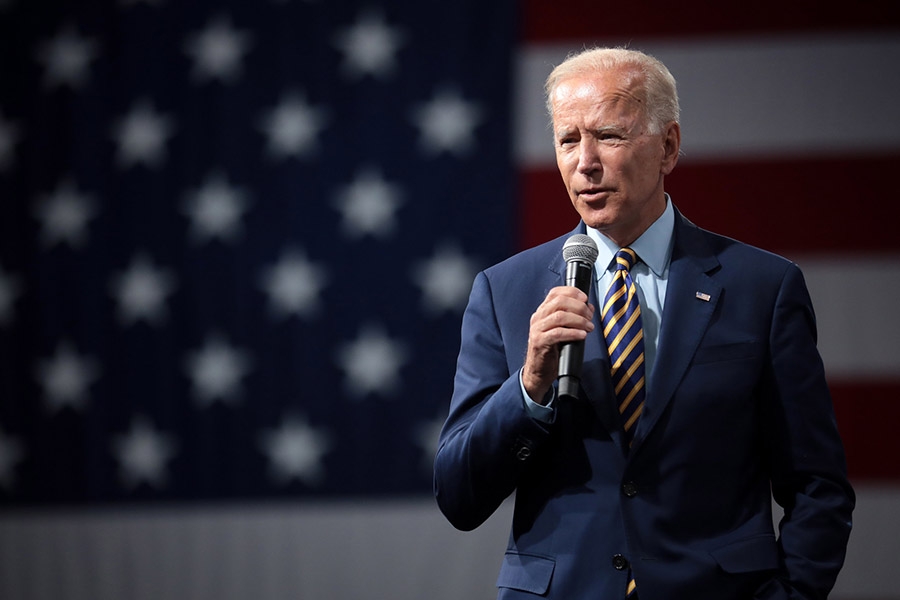

Joe Biden’s Foreign Policy — What Can We Expect?

by Richard Maude, Senior Fellow, Asia Society Policy Institute

Joe Biden will come to the Presidency with an internationalist mindset and an ambitious agenda to renew U.S. global leadership. He offers a vision that is the antithesis of the flawed nationalism and narrow self-interest of President Trump’s “America First”.

Biden’s critique of Trump’s foreign policy is direct and clear. He argues the Trump Administration alienated allies, emboldened autocrats and “trashed” the sources of US soft power. Withdrawal from international commitments like the Paris climate change agreement damaged U.S. credibility. China policy was confrontational without being competitive.

No president gets an entirely free hand on foreign policy and Biden won’t be any different. At home, fighting the pandemic and repairing the economy will be immense and complex priorities.

Trump’s defeat won’t end political polarisation in Washington. And if the Republican Party holds the Senate, Biden will have significantly less freedom to pursue his agenda through legislation.

Funding for transformational climate change policies will be harder to secure (although not necessarily impossible). Nor will Biden always get his first picks for key Cabinet positions. Supreme Court challenges might throw up other obstacles.

Internationally, the Biden team confronts a poorer, meaner and more fractured world. Liberalism is in retreat, nationalism resurgent, and major power competition the defining strategic dynamic. Biden’s foreign policy must reflect these new realities or it will fail.

Still, Biden and his team know where they want to start. Biden has said he will take “decisive steps” to renew America’s “core values” so that the United States can once again lead by the power of example. He wants to call a summit of democracies early in his presidency and has made the renewal of international democracy promotion a signature initiative.

Climate change is a top priority. The president-elect talks of a revolution in America’s approach, arguing that ambition on an “epic scale” is needed.

Under Biden, the United States will re-join the Paris climate change agreement and commit to net zero emissions by 2050. The Democratic Party’s climate change plan promises huge investments in climate resilience, energy efficiency, and research and innovation (Congress willing).

Biden has also promised to “lead an effort to get every major country to ramp up the ambition of their domestic climate targets.” With China, Japan, and South Korea all committing recently to net zero emissions by mid-century (2060 in China’s case), Australia’s lack of climate change ambition is increasingly exposed. Biden might just choose to start his global campaign in Canberra.

Biden has promised to restore America’s regard for U.S. allies and to use these partnerships more effectively to compete with China and advance shared national interests. Under Biden, the United States will re-engage with the multilateral system, including bodies targeted by the Trump Administration, like the World Health Organization and World Trade Organization. All of this supports Australian national interests.

We should expect a Biden Administration to be more pro-trade and less obsessed with trade deficits than Trump’s White House. But Australia should understand there will be no return to neoliberalism. Biden’s campaign platform is built on the politics and economics of middle-class disadvantage. This reflects now mainstream concerns about the negative effects of globalisation on working families, particularly the swathe cut through U.S. manufacturing in recent decades by trade competition and automation

The Biden Administration will continue to pursue “fair trade”, especially with China. Biden has a big “Buy America” plan and has foreshadowed large investments in innovation and technology. He sees manufacturing in the United States as helping “fuel an economic recovery for working families."

Biden has left the door ever so slightly ajar for a U.S. return to the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), but this won’t be contemplated until his administration has “invested in Americans and equipped them to succeed in the global economy.”

Nor is it likely the United States would contemplate joining the agreement in its current form. A Biden Administration would ask for changes that CPTPP members might find unpalatable, such as more labour and environmental protections and stronger intellectual property disciplines. Finally, the Congressional politics of re-joining CPTPP will remain difficult. An interim sectoral deal might be the best medium-term prospect.

China will be Biden’s biggest foreign policy challenge. We have some guideposts on policy but nothing yet that qualifies as a comprehensive strategy to deal with a peer competitor like no other the United states has faced. This remains to be written. And as Thomas Wright observes, views within the centrist wing of the Democratic Party differ on what to do about China.

Still, some things are clear. First, if views about policy options differ, there is little disagreement that the challenge from China to U.S. interests is severe. Biden himself has been rhetorically hard-line on China, especially its hardening authoritarianism, human rights violations and trade practices. A tougher, more competitive relationship is here to stay. This is certainly what China’s leaders expect.

Second, Biden believes the challenge from China will be more effectively met if the United States invests more in its democracy and its economic and technological strength, and if Washington works more closely with allies and close partners. Australia will want to keep some freedom to manoeuvre when it comes to its difficult relationship with China, but more coordinated push-back could also help Canberra with some challenges, like Beijing’s coercive economic punishments.

Third, the Democrats want to find some space within a more competitive relationship with China to maintain lines of communication, manage the risk of military-to-military clashes and other crises, and advance global agendas, especially climate change.

Biden has been critical of Trump’s tariff blunderbuss, noting its cost to U.S. farmers (not to mention the U.S. Treasury in farm support). He might shift to a more targeted approach in the expectation China would follow. Similarly, while there won’t be any fundamental shift on red lines like keeping Chinese companies out of America’s 5G networks, Biden might put some boundaries around the Trump Administration’s tech war (Silicon Valley, a major donor, certainly hopes so).

A U.S. competing toughly with China, especially in the Indo-Pacific, but within agreed red lines and with flash points more effectively managed would be a good outcome for Australia.

Getting there won’t be easy. If the old U.S. model of engagement failed to change China’s behaviour, there are no signs that President Trump’s battering ram was going to have any more luck. The dilemma Biden confronts is that China is now probably too powerful and too confident, and too fixed on the perceived risks a truly reciprocal relationship with the democratic West might pose to the Party’s position in China, to contemplate much more that tactical calibrations in its domestic and foreign policies.

That doesn’t mean an uneasy co-existence is impossible, but it does mean the U.S. and its allies will have to keep hardening themselves for the long haul. Biden will have to exercise U.S. power in ways that might not come instinctively to him. At least some in Asia worry he will ease pressure on China too much.

Elsewhere in Asia, U.S. relations with India and Japan are set to keep strengthening. Biden won’t want to provoke a crisis over Taiwan but nor is he likely to walk back from a path of stronger support for Taipei. That might include a free trade agreement, if Trump doesn’t get there first in his remaining days.

Most Southeast Asian governments will welcome Biden’s different approach, but U.S. strategy in this vital region needs a revamp to compete more effectively with China. And a foreign policy driven more by values could be a point of friction. Some of the pressure should ease on the creaking U.S.-ROK alliance, which Australia will welcome, but north of Seoul Biden won’t have any more luck than those who preceded him in freeing North Korea’s grasp from its nuclear weapons.

Richard Maude is Executive Director of Policy at Asia Society Australia and a Senior Fellow of the Asia Society Policy Institute.

Asia Society Australia acknowledges the support of the Victorian Government.