What Is Baijiu? A Primer to China's Infamous Alcoholic Staple

When the American writer Derek Sandhaus arrived in Shanghai in 2006, he soon encountered Chinese baijiu — a fiery and powerful liquor found at dining room tables and bars across the country. He didn’t think much of it at first.

"I was at a party,” he explained, “and someone put something in front of me and said, ‘Hey, drink this!’ I did, and asked the common follow-up question: ‘What the hell did you just give me?’”

Ask any Westerner who has spent time in China, and their own story would likely be the same. But during a later stint in Chengdu, the gray, bustling capital of China’s Sichuan Province, Sandhaus was re-introduced to baijiu by two men who worked in the industry. This time, he began to understand that there was more to the popular beverage than he had thought.

“I discovered it wasn’t nearly as gross or intimidating as I thought it was,” he recalled. “And for a writer, it was an incredibly complex and interesting subject with offshoots in just about every aspect of life in China.”

Eventually, Sandhaus’ fascination with baijiu resulted in a book, Baijiu: The Essential Guide to Chinese Spirits, which seeks to demystify and rehabilitate the much-maligned drink. In fact, baijiu is having a moment: The quintessentially Chinese spirit has become more popular in other parts of Asia, particularly in South Korea, and has even found its way into bars and supermarkets in the U.S. Could baijiu be the next hot international liquor trend?

With Sandhaus’ help, here is a brief rundown of everything you need to know about baijiu.

What Is Baijiu, Exactly?

Baijiu is a clear grain alcohol that resembles (in color) other East Asian liquors like South Korea’s soju. The main difference between baijiu and these liquors is the former’s strength — a typical baijiu might exceed 110 proof (55 percent alcohol content). While baijiu is often consumed straight-up in shots or sipped, cocktails mixing baijiu with other flavors have recently become more popular.

Just like whiskey, gin, and other spirits, “baijiu” isn't just one thing — it instead refers to a wide variety of substances. There are many different kinds of baijiu, but the four main types are loosely defined as the rice aroma (a floral, light flavor), light aroma (a sweet, floral taste), sauce aroma (a sharp taste akin to soy sauce), and strong aroma (spicy and fruity), and within these broad categories there are countless additional variations.

Sandhaus says that it is not surprising that nearly all Western visitors to China find baijiu so peculiar at first.

“The flavors or smells are very different than what you get with a whiskey or vodka or rum,” he said. “It’s something strange for the Western palette.”

Who Drinks Baijiu?

A lot of people. Baijiu can be found everywhere in China. It is sold in supermarkets in Shanghai and in corner stores in tiny villages. It can be bought in Tibet, Xinjiang, Yunnan, Inner Mongolia, and everywhere else. It is found in the liquor cabinets of rich and poor and everyone in between. If you are anywhere in China, you will not be far from baijiu.

Over 1.5 billion gallons of baijiu were sold last year for a total profit of $23 billion. This makes it the best-selling spirit in the world — even though the overwhelming majority of its drinkers are in one country.

In the larger Chinese cities, Western spirits like whiskey and gin have become increasingly popular with the young. Might they threaten baijiu’s dominance? Sandhaus doesn’t think so. He estimates that 99 percent of the hard liquor drunk in China is baijiu, a figure that is unlikely to drop very much.

Why is baijiu so common? Sandhaus says that one major factor is ritualistic. Baijiu is found at weddings, funerals, holidays, and other events. But an important reason for its ubiquity is how embedded it is in China’s business culture. Business deals and promotions are often cemented at tables adorned with baijiu bottles, and one tends to encounter more the higher one gets in an organization. Sandhaus notes that China is one of the world’s only countries where a person’s peak drinking years occur in their 40s and 50s, rather than in their 20s, as in most of the world.

“Baijiu companies don’t need to worry that nobody will be drinking their product in the years to come,” Sandhaus said.

If anything, baijiu’s foothold in the global market is only going to grow as imbibers in other countries get exposed to it.

Baijiu drinking is still largely a male activity in China, but this has less to do with the spirit itself than with the broader drinking culture in China. Historically, women in China were discouraged and excused from the ritualistic drinking required of men. As China has urbanized, this has changed to an extent — but women still drink significantly less often. A World Health Organization report published in 2010 found that more than two-thirds of Chinese women did not drink at all. And for every woman in the country who suffers from “alcohol use disorder,” 47 men do. So while Chinese women are markedly less likely to drink at all, those that do will not necessarily choose another type of alcohol over baijiu.

Where Can I Get My Hands on Some Baijiu?

Just about any decent Chinese supermarket will have a few bottles in stock, and a well-stocked bar in a decent-sized city may have a bottle or two tucked away. But for the curious in the New York City area, Manhattan now boasts its very own baijiu-themed bar — Lumos, in Soho. Sandhaus recommends a curious patron sample three things — a classic straight shot of baijiu, a shot of baijiu infused with a separate flavor, and one of Lumos’ signature baijiu cocktails. (Though at a head-spinning 110 proof or more, drink this amount at your own risk.)

What Are the Most Common Types of Baijiu? What Type Should I Try?

There are many, many types of baijiu sold in China. Two of the most prevalent are Maotai and Eerguotou. And the two couldn’t be much more different.

Maotai is tasty, powerful, refined, and very expensive. It isn’t easy getting a good bottle of the stuff for less than $50, while at the top end the sky's the limit: bottles selling for hundreds and even thousands of dollars are not uncommon.

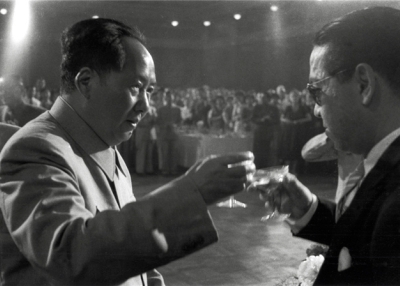

As a result, Maotai bottles are typically only found at special functions. In 1974, then-U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger reportedly told Deng Xiaoping, the high-ranking Communist official who would lead China for two decades, “if we drink enough Maotai, we can solve anything.”

(Note: Asia Society does not endorse applying this maxim in practice.)

If Maotai is the Ferrari of baijiu, Erguotou might better resemble a children’s tricycle — with two broken wheels. At $1.50 or so a bottle, Erguotou might be one of the cheapest ways in the world to spend a boozy evening and is particularly popular with blue-collar workers in China.

Naturally, the vast majority of baijiu falls in between these two price points. This article provides a decent overview of China’s most popular types.

Sandhaus cited two types of baijiu that he considers suitable for beginners. Here’s what he had to say about each:

Luzhou Laojiao

“This is a good beginner’s baijiu from Sichuan Province. It’s a ‘strong aroma baijiu,’ probably the most common kind in the county, and is remarkably easy to drink. It’s got a lot of nice tropical fruit flavors and also some anise. It’s quite strong, but it’s also pleasant and approachable. I recommend drinking it with spicy Sichuan food — that’s the best way to go. You can find it in a lot of Chinatowns — certainly in New York.”

Guilin San Hua

“In contrast to Luzhou Laojiao, Guilin San Hua is a lot harder to find in the U.S.; in fact, I don’t know if you can find it here at all. When I’m in China, I like to drink rice baijiu, which tends to be very approachable for foreigners. Guilin San Hua is a spirit distilled from glutinous rice called Lao Guilin. It has the same basic flavor profile as [Japanese] sake. It’s really easy to drink and, without exception, every drinker I’ve introduced to Guilin San Hua has told me they liked it. But it isn’t as representative as Luzhou Laojiao.”