The COVID New (Ab)Normal: India’s China Challenge and the American Alignment

C. Raja Mohan

Indian Border Security Force (BSF) personnel stand in a formation during a ceremony to celebrate India's 74th Independence Day, which marks the end of British colonial rule, in Srinagar on August 15, 2020. India's Prime Minister Narendra Modi issued a new warning to China over deadly border tensions on August 15, using his most important speech of the year to promise to build a stronger military. (Tauseef Mustafa / AFP)

The COVID-19 crisis sharpened India’s two major strategic challenges. One was the economic slowdown of recent years, and the other was the gathering military challenge on its long and contested frontiers with China. The economic contraction imposed by the pandemic and China’s recent aggression in the high Himalayas compelled India to embark on a major reorientation of its economic and foreign policies. Delhi’s new policy approach promises to be quite consequential for the evolution of India’s domestic and international policies.

The massive economic disruption triggered by the coronavirus has compelled Prime Minister Narendra Modi to unveil a series of economic reforms and a broad political framework under which they could be pursued. India’s economic restructuring has also tied in closely with the reordering of India’s great power relations, which has been hastened by Chinese aggression in the eastern Ladakh border region. India’s retaliation focused on horizontal economic escalation rather than a vertical military one. Delhi has threatened commercial dissociation from China in order to persuade Beijing to restore the territorial status quo in eastern Ladakh that obtained prior to the People’s Liberation Army aggression in May. The confrontation with China has also encouraged India to intensify its growing security partnership with the United States.

If Beijing has been the source of many recent economic and foreign policy changes in Delhi, Washington has increasingly become central to India’s answers. Although there is much uncertainty in America’s own future direction and its relationship with China, the prospects for deeper strategic partnership between Delhi and Washington have improved significantly. These forces have brought India’s strategic policies to an important inflection point.

Decoupling from China

The Indian economy was slowing down through the 2010s after reaching unprecedented growth rates of close to 9 per cent in the mid-2000s. The expectation that Prime Minister Modi, elected as prime minister in 2014 with an impressive mandate, would give a fresh impetus to India’s growth trajectory were quickly belied.

Modi was the first Indian PM to enjoy a majority in the Lok Sabha after Rajiv Gandhi’s massive electoral victory in the 1984 elections that followed the assassination of his mother, Indira Gandhi. Modi also came to Delhi with the reputation of being a big reformer. But Modi surprised most observers with his unwillingness to promote sweeping change during his first term. The two major actions he did take — demonetization and the GST — only seemed to harm the economy. Modi also signaled his opposition to trade liberalization, by asking his government to review all previous trade agreements.

The pandemic, which came on top of this crisis, left Delhi with no option but to undertake serious reform and consider opening up further. In the summer of 2020, the Modi government announced a number of reforms. These included lowering taxes, ending a state monopoly on agricultural trade, privatizing state-owned enterprises, lifting caps on foreign direct investment, and opening up additional sectors for private enterprise, among others. The government also created a new scheme of production-linked-incentives to promote manufacturing in India. In September, Modi got parliamentary approval for laws that make it easier for farmers to sell their produce directly to non-state entities and liberalize labor rules. Some BJP-led state governments also announced the temporary suspension of labor laws to attract investments.

Tying all these initiatives together was a new framework for promoting economic self-reliance under the new political campaign Atmanirbhar Bharat. Unsurprisingly, Modi’s invocation of a "self-reliant India" triggered many questions among India’s economic partners. Is Modi walking India back from the strategy of globalization adopted in the early 1990s? Senior ministers and officials in Delhi were at pains to emphasize that the focus was on strengthening India’s participation in the global economy rather than retreating from it. The government underlined its special commitment to India becoming a part of global value chains. The emphasis on self-reliance seemed to offer a new and interesting political framework for India’s reforms. Unlike in the past, when India was seen to be responding to external pressures to adapt, here Modi was framing the reforms in nationalist terms that were acceptable to the Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh, the ideological parent of the ruling party.

The new campaign for self-reliance includes a special commitment to restore India’s manufacturing capabilities that were seen as losing out to India’s embrace of free trade since the 1990s. The problems with India’s rapidly expanding commercial relationship with China came into view in the 2010s as the bilateral trade deficit steadily rose to nearly $55 billion in 2019. Even more important was the fact that the import of cheap manufactured goods from China was wiping out India’s industrial base.

Modi ended Delhi’s inaction when he pulled India out of an Asia-wide free trade arrangement called Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership in late 2019. Delhi had concluded that a China-led economic order in Asia will permanently doom India’s prospects. Then, Beijing’s Ladakh aggression forced India to go from passive commercial withdrawal to active economic decoupling from China. India took a series of steps to limit imports from China, constrain Chinese investments, limit India’s exposure to China’s digital companies, and signal the likelihood of blocking Huawei and ZTE from India’s rollout of the fifth generation cellular technology.

Aligning with America

As Delhi begins to delink its economy from China’s, the post-pandemic environment has opened the door for a more intensive commercial engagement with the United States, already India’s largest trade partner (bilateral trade stood at $160 billion in 2019). While there are multiple disputes in the economic partnership, there is a new force binding them together. India is trying to attract U.S. companies, such as Apple, that are currently manufacturing in China but are looking to diversify their supply chains amid the trade war between Washington and Beijing.

Since the COVID-19 crisis enveloped the world, India has been part of talks initiated by the Trump administration to reduce excessive dependence on China and reorient global supply chains towards a network of trusted partners. As the United States takes a fresh look at its China policy and explores new ways of dealing with the challenges being posed by Beijing, Delhi figures prominently in the new Washington discourse in multiple ways — from new supply chain networks to a coalition of democracies and stronger Indo-Pacific security partnerships.

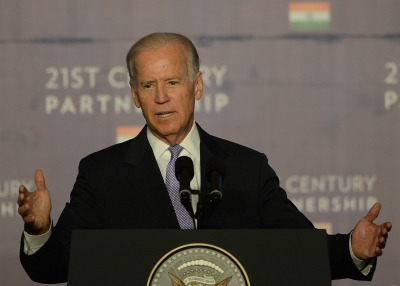

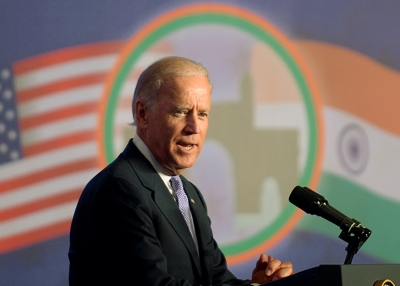

Meanwhile, India under Modi has slowly shed many of the historic hesitations about drawing closer to the United States, especially in the security domain. If his predecessor Manmohan Singh was tied down by the ideological reservations of the Indian National Congress against a strategic embrace of the United States, Modi was determined to transform the partnership with America and found ways to overcome the traditional nativist opposition to the United States in his own Bharatiya Janata Party. From inviting an American president (Barack Obama) for the first time as the honored guest at India’s annual Republic Day celebrations to flipping India’s position on climate change to work with the United States, and from reviving the “quad” framework with the United States, Japan and Australia to signing the so-called foundational military agreements with Washington, Modi took steps that had become quite inconceivable during the Manmohan Singh-led United Progressive Alliance decade.

The post-pandemic environment and China’s aggression in India’s eastern Ladakh region has only sharpened the case in Delhi for a stronger security partnership with Washington. For more than a decade, realists in Delhi were pointing to India’s mounting China challenge. Although India had a long record of befriending China, Beijing has been unresponsive to India’s concerns — whether it is the boundary dispute or the trade deficit. And as the gap in their comprehensive national power widened in favor of Beijing (China’s GDP of $14 trillion is nearly five times larger than that of India’s, which barely touches $3 trillion), the traditional perception in Delhi of a broad parity with China had become unsustainable.

It is replaced by the recognition that China was and is rapidly expanding its strategic influence in India’s near and extended neighborhood at Delhi’s expense. This was reinforced by China’s brazen efforts to block India’s larger international aspirations — whether it was a permanent seat at the UNSC or the membership of the Nuclear Suppliers Group. Delhi also discovered that the wider the gap in comprehensive national power, the less sensitive China was to India’s concerns.

Even during Modi’s first term, however, the realists could not overcome Delhi’s entrenched ambivalence towards Beijing. China’s aggression in Ladakh has ended India’s reluctance to confront the military and economic challenges posed by China. Like all major interlocutors of China, Delhi would prefer managing the difficulties through dialogue with Beijing rather than embark on a confrontation. But Beijing has left Delhi with no other choice but to respond vigorously. Delhi is also acutely aware, that U.S. policy towards China has entered a period of unpredictability and that it cannot rely on Washington to resolve its problems with Beijing. Nevertheless, Delhi is preparing to stand up to the China challenge with or without American support in this definitive moment of its national evolution.

Professor C. Raja Mohan is the Director of the Institute of South Asian Studies at the National University of Singapore.