Chinese Diplomacy in Southeast Asia during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Executive Summary

- Even as the COVID-19 pandemic struck Southeast Asia with the force of a great Indian Ocean tsunami, China sought to find opportunity in the crisis.

- China’s heavily promoted pandemic aid, especially the supply of vaccines when these were in very short supply from the West, won gratitude from regional elites. China’s high-level bilateral and regional diplomacy kept up a brisk pace while the region’s other major partners were focused at home. China’s ability to contain the pandemic in 2020 and 2021 and keep its economy open lifted bilateral trade, positioning China as the road to economic recovery.

- China used its “discourse power” and heavy presence in local media to hit back at criticism of its early mishandling of the pandemic and to portray China as a responsible great power standing shoulder-to-shoulder with the region in its time of need. Southeast Asian countries pragmatically declined to participate in global finger-pointing over the origins of the pandemic.

- However, case studies of Indonesia, the Philippines, and Thailand also reveal factors that acted to constrain the growth of China’s influence during the pandemic.

- These include China’s heavy-handed assertion of maritime claims in the South China Sea, China’s propensity to over-sell and under-deliver on infrastructure projects, low public trust in China, ingrained wariness of China in some institutions of state, especially militaries, and the arrival of more effective vaccines from the United States and other bilateral partners, along with the COVAX initiative.

- This report judges China increased its influence in Indonesia during the pandemic, a product of pandemic aid, trade and investment ties, and influence with elites. In the Philippines, the long-term trend favors the growth of Chinese influence, but tension over maritime disputes, especially in 2021, undercut both goodwill from China’s pandemic aid and Beijing’s ambition to weaken the U.S.-Philippines Alliance. China gave relatively less pandemic aid to Thailand and paid it relatively less diplomatic attention through 2020 and 2021. Still, China’s natural advantages (proximity, trade, Thailand’s authoritarian tilt, for example) kept its influence levels steady.

- The longer-term trend favors the continued increase of Chinese influence in Southeast Asia relative to other major partners. Southeast Asia’s strategy for dealing with growing Chinese influence and sharper U.S.-China competition remains in the main to avoid leaning too close too often to either of the major powers and thus to avoid difficult choices.

- The sustainability of this strategy in the face of Chinese power and proximity is far from assured. One plausible future for the region is of creeping accommodation of, and deference to, China’s interests. Along the way, China could increase its “veto power” over the foreign policies of Southeast Asian countries, including when it comes to cooperation with other regional partners like the United States, Australia, and Japan.

- The United States and close partners are increasing their investment in bilateral and regional initiatives in Southeast Asia in response to China’s active diplomacy. The pandemic period offers broad lessons for the future. The United States cannot afford to be missing in action when the next crisis hits the region. Getting the basics right in Southeast Asia means giving attention to the whole region, not just a few countries. The right narrative matters, for example stressing shared principles, like the inviolability of sovereignty, rather than values is the best approach. More can be done to support Southeast Asia’s economic recovery, including in areas of comparative advantage such as supporting clean energy transitions, building human capital, and deepening the burgeoning digital economy. Programs to build influence with regional elites need turbocharging. Finally, the United States and its close partners must find ways of engaging in the information war in Southeast Asia with greater effect.

Introduction

On 13 January 2020, a 61-year-old woman in Thailand was confirmed as carrying the mysterious but fearsome respiratory virus known to be circulating in China’s central Hubei province and striking down even the fit and healthy. The woman, a tourist from Wuhan, is unlucky enough to be recorded by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the first case of COVID-19 outside China.

By March, the virus was spreading rapidly through Southeast Asia, as it was globally, and the WHO declared a pandemic.

Like the rest of the world, Southeast Asia has endured three primary waves of the pandemic. In 2020, the region was successful in keeping the worst of COVID at bay, albeit at enormous economic cost. In mid-2021, a deadly Delta wave struck, overwhelming the defences of nearly all of the region’s countries, killing tens of thousands, and threatening economic recovery. In the early months of 2022, the Omicron variant began spreading rapidly. Infections rose sharply, but not so the death rate – a much hoped for partial “decoupling” created by Omicron’s lower lethality and growing vaccine coverage. Increasingly, Southeast Asia is learning to live with COVID.

The pandemic years of 2020 and 2021 should be seen in the context of a much longer period of increased Chinese attention to, and investment in, its relationships in Southeast Asia.

China seeks to build influence in Southeast Asia through its “peripheral diplomacy,” which seeks a stable and unthreatening near abroad, economic opportunity and – ultimately – a Beijing-centric regional order in which China is pre-eminent and the region’s countries defer to its interests and authority.

Influence is the primary goal of day-to-day diplomacy. Nations seek to build influence in and with other countries as a means to an end. These ends include attracting the attention of decision-makers and building goodwill. Influence is also useful at a more transactional level – to support business deals or seal military contracts, for example. And nations also want influence to ensure other countries support, or at least not oppose, important foreign policy objectives and domestic issues.

The COVID pandemic also coincided with a rapid deterioration in U.S.-China relations and a sharp rise in major power contestation over both power and values. Efforts by the United States and its allies and close partners to balance China’s power in the Indo-Pacific, including in Southeast Asia, have accelerated.

Southeast Asian countries are not passive actors in this story. The region’s countries have long viewed China through multiple lenses – a mixture of “expectation and fear, aspiration and frustration.”1 The history of China-Southeast Asia relations is full of examples of regional countries exercising agency to protect their interests.

Still, as it grapples with the pandemic, Southeast Asia feels increasingly squeezed by this contestation. It worries about China’s future intentions and the risk of conflict, but its economies are deeply integrated with that of China. It does not want to “choose” between the United States and China and seeks to protect the “centrality” of institutions led by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), like the East Asia Summit to Indo-Pacific affairs. The cohesion of the ten-member bloc is strained.

Against this backdrop – two years of loss and suffering, of hard-won gains against COVID, and tumultuous international events – this report provides a brief overview of the practice of Chinese diplomacy in ASEAN member states through the pandemic years of 2020 and 2021.

It begins with an examination of the place of Southeast Asia in China’s world view and foreign policy. It then illustrates aspects of China’s political, security, and economic relations with Southeast Asia through this period, using quantitative data on political, economic, and social factors.

The report offers a net assessment of China’s pandemic diplomacy and then delves deeper with three case studies covering Indonesia, the Philippines, and Thailand. These case studies track major developments in relations with China during that period and try to come to some judgements about China’s standing and influence at the end of 2021.

Finally, the report offers thoughts on policy implications for the United States and close partners, especially Australia and Japan.

Judgements about influence in this report are based on both quantitative (e.g., economic links) and qualitative factors (including the views of experts in and on Southeast Asia interviewed for this project). As with all attempts to quantify influence, which we distinguish from power, they are necessarily imperfect and subjective.

Influence inevitably has its limits, even in countries that are closely aligned. As a large 2021 RAND Corporation Study on China’s attempts to build global influence found, turning influence into favorable outcomes, especially where these are very broad (such as a country’s strategic alignment), depends on many internal and external variables. The case studies demonstrate some of these variables at work during the pandemic.2

1 Murray Hiebert, Under Beijing’s Shadow: Southeast Asia’s China Challenge, Centre for Strategic and International Studies 2020 p 5.

2 Mazarr, Michael J., Bryan Frederick, John J. Drennan, Emily Ellinger, Kelly Elizabeth Eusebi, Bryan Rooney, Andrew Stravers, and Emily Yoder, Understanding Influence in the Strategic Competition with China. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2021.

Southeast Asia and China’s Great National Rejuvenation

China seeks material advantage – wealth and security – in its relations with Southeast Asia, as all the region’s major external partners do. But Southeast Asia also has a central place in China’s ambition to create a more China-centric regional order in which the United States and its allies and close partners have less influence and Asia looks first to Beijing.

China’s approach to Southeast Asia mixes old and new foreign policy approaches.

Longstanding concepts include an emphasis on China’s “peaceful development” and the framing of China as a good neighbor, partner, and friend of Southeast Asia.

Newer concepts reflect the stamp President Xi Jinping has put on contemporary Chinese Communist Party (CCP) ideology, now canonized and incorporated into the CCP’s constitution, including through Xi Jinping Thought on Diplomacy. Prominent among these concepts is Beijing’s appeal to ASEAN to work with it to build a “closer China-ASEAN community with a shared future.”1

According to China’s leaders, the aspiration for a global community with a shared future for mankind “epitomizes a long-cherished Chinese vision of promoting common good and universal peace”2. Beijing argues its vision for ASEAN-China ties stands in contrast to the “Cold War” mentality of the United States. China, Southeast Asia is told, stands against bloc-ism and “zero sum” competition, does not seek hegemony, and will never bully smaller countries.

Xi’s new, vaguely defined Global Security Initiative reflects this intensifying contest for the shape and character of regional order. Beijing says the initiative has been launched “in order to foster a new type of security that replaces confrontation, alliance and a zero-sum approach with dialogue, partnership and ‘win-win’ results”3.

Similarly, Xi’s Global Development Initiative positions China as an empathetic friend of the global south, including Southeast Asia, and a fellow developing country seeking to advance “greener and more balanced development” through “open and inclusive partnerships”4.

Beijing describes China-Southeast Asia cooperation to fight the pandemic as an “exemplary model” of this “new type” of international relations5.

Against this background, China’s foreign policy objectives in Southeast Asia could be summarized as:

- Establishing a China-centric region, in which the countries of Southeast Asia are highly connected to China by the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and manufacturing supply chains, and there is deference to China’s interests and authority (what the analyst Nadège Rolland describes as an aspiration for “soft” hegemony);

- Exerting sufficient political influence to prevent Southeast Asian states from aligning with the United States or its partners, and from supporting elements of the U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy (for example, the Quad, AUKUS, stronger defense cooperation between Southeast Asia and the United States and its partners, joint maritime patrols in the South China Sea)6;

- Gaining acceptance of China’s sovereignty claims in the South China Sea or, failing that, de-facto control of the area;

- Ensuring stability and security along China’s borders;

- Securing access to energy and resources to support China’s economic growth;

- Opening markets for China’s exports and investment opportunities for China’s manufacturers;

- Ensuring China is the preferred destination for Southeast Asian elites when it comes to study and professional exchanges.

Foreign policy as a tool for rejuvenation

China’s leaders stress the importance of foreign policy and diplomacy as part of an overarching strategy to rejuvenate the Chinese nation7. And China’s relations with its neighboring countries are seen as particularly important to the goal of national rejuvenation, second only to the task of managing relations with the United States, Russia, and the European Union (EU). Xi established neighborhood (or periphery) diplomacy as a central focus of Chinese foreign policy at a Peripheral Diplomacy conference in October 2013 and again at the Central Foreign Affairs Work Conference in 2014.

Like it has world-wide, Chinese diplomacy in Southeast Asia has become more assertive and confident in pursuing Chinese national interests, enabled by China’s new power and encapsulated in the transition in internal Party thinking from the importance of China “keeping a low profile” to “striving for achievement.” The Party sees China as standing “taller and prouder among the nations of the world.”

Observers of Southeast Asia usually date this shift back to 2009, a point when China began more forcefully asserting its right to claim the vast maritime area of the South China Sea encompassed by its “nine dash line.” “Increasingly less charm and more offensive,” is how the author Sebastian Strangio summarizes the new era.8

All arms of statecraft

Like Southeast Asia’s other major partners, China uses all arms of statecraft to advance its foreign policy objectives. China’s principal arms of policy encompass economic, security, diplomatic and soft power. The economic arm is perhaps the most well developed and includes the BRI and China’s free trade agreement with ASEAN. It also includes tourism and investment, comprising foreign direct investment, soft loans, development cooperation, and now also pandemic aid.

The security arm of statecraft is enforced through substantial deployment of military power, notably in the South China Sea, along with bilateral and regional defence diplomacy.

China’s soft power comes from its efforts to strengthen ties with elites across the political spectrum; significant investment in people-to-people links, including scholarships and professional training; as well as exchanges for regional officials and military officers. It also promotes cultural initiatives, like sister-city relationships and Confucius Institutes.9

China’s engagement in Southeast Asia is supported by active diplomacy and a substantial on-the-ground presence, including the largest network of diplomatic missions compared with other external partners in the region.

China also deploys its considerable “discourse power” in support of its foreign policy objectives. This is amplified by partnerships with local media platforms, Chinese digital news apps, and an active diplomatic presence on Facebook and (to a lesser extent) Twitter.

Beijing also increasingly seeks to enlist the Chinese diaspora in Southeast Asia to help advance its interests in the region. Xi has described China’s very large global diaspora as part of “one big family” and important to the dream of national rejuvenation. Beijing uses overseas Chinese communities in both benign (e.g., cultural promotion) and more covert ways, including to develop political influence.10 This is sensitive ground in parts of Southeast Asia, where latent racism and lingering suspicion of Chinese communities dating from the 1960s, when Beijing supported communist insurgencies in the region, are easily aroused.

The gravitational pull of China’s economy, its geographical proximity and growing infrastructure connectivity, and the sustained attention and engagement across all arms of statecraft Beijing has given Southeast Asia in recent years has seen its presence, role and influence grow considerably.

In the 2022 ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute State of Southeast Asia Survey, which surveys government, business, and civil society elites, nearly 77 percent of respondents saw China as the most influential economic power in the region and 54 percent saw China as the most influential political and strategic power in the region.

The terrible COVID pandemic years of 2020 and 2021 will not alter this long-term trajectory. But an examination of this period illuminates both China’s advantages and the limits of its influence. Elements of far-reaching ambition are clear in Southeast Asia, but so too are the many variables that work against China’s objectives and influence, including the wishes and actions of the countries of the region themselves

1 See, for example, Xi Jinping’s speech to the special summit commemorating the 30th anniversary of China-ASEAN dialogue relations, given on 22 November 2021. The joint ASEAN-China statement from the summit “acknowledges” China’s vision, but ASEAN stopped short of a full endorsement. See also Hoang Thi Ha, “Understanding China’s Proposal for an ASEAN-China Community of Common Destiny and ASEAN’s Ambivalent Response,” Contemporary Southeast Asia, Vol 41, No 2 (August 2019).

2 Speech by China’s State Councilor and Foreign Minister, Wang Yi, at the inauguration of the Xi Jinping Thought on Diplomacy Studies Centre on 20 July 2020

3 See, for example, speech by Vice Foreign Minister Le Yucheng at the "Seeking Peace and Promoting Development” online dialogue of think tanks from 20 countries, 6 May 2022

4 Remarks by State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi at the opening ceremony of the Sustainable Development Forum 2021, 26 September 2021

5 Opinion piece by China’s Ambassador to ASEAN, Deng Xijung, Jakarta Post, 20 November 2021

6 See also Mingjiang Li, “Southeast Asia Through Chinese Eyes,” in The Deer and the Dragon: Southeast Asia in the 21st Century, ed Emerson

7 Speech by China’s State Councilor and Foreign Minister, Wang Yi, at the inauguration of the Xi Jinping Thought on Diplomacy Studies Centre” on 20 July 2020

8 Sebastian Strangio, In the Dragon’s Shadow: Southeast Asia in the Chinese Century (Yale University Press, 2020), 10-23

9 For a good overview, see chapter one of Murray Hiebert, Under Beijing’s Shadow: Southeast Asia’s China Challenge (Rowman and Littlefield, 2020)

10 Paul Charon and Jean-Baptiste Jeangène Vilmer, Chinese Influence Operations: A Machiavellian Moment, Institut de Recherche Strategique de l’Ecole Militaire 2021. P 42 and 165-169. See also Geoff Wade, “Re-enlisting the Diaspora: Beijing and the Overseas Chinese,” in The Deer and the Dragon: Southeast Asia in the 21st Century, ed Emerson

Chinese Diplomacy in Southeast Asia: Insights Through Data

In this chapter we explore some metrics of China’s engagement with Southeast Asia and, where possible, how they changed during the pandemic. Some key takeaways:

- China led on vaccines donations from late 2020 but was surpassed by the United States by end 2021;

- China sold rather than donated most of its vaccines;

- Trade with China grew during the pandemic and ASEAN became China’s largest trading partner;

- China largely lags the United States and Japan in terms of foreign direct investment (FDI) in Southeast Asia, but its investments in Indonesia, the Philippines, and Thailand, are increasing;

- The pandemic significantly restricted people-to-people flows, one of China’s major soft power and foreign policy assets (especially education and tourism), but China’s high-level diplomacy, including through travel and in-person meetings, continued through the 2020 and 2021;

- Regional elites gave more credit to China than the United States for pandemic assistance, but this has not translated into greater trust in China across Southeast Asia (albeit with variations across particular countries).

Missions and partnership type

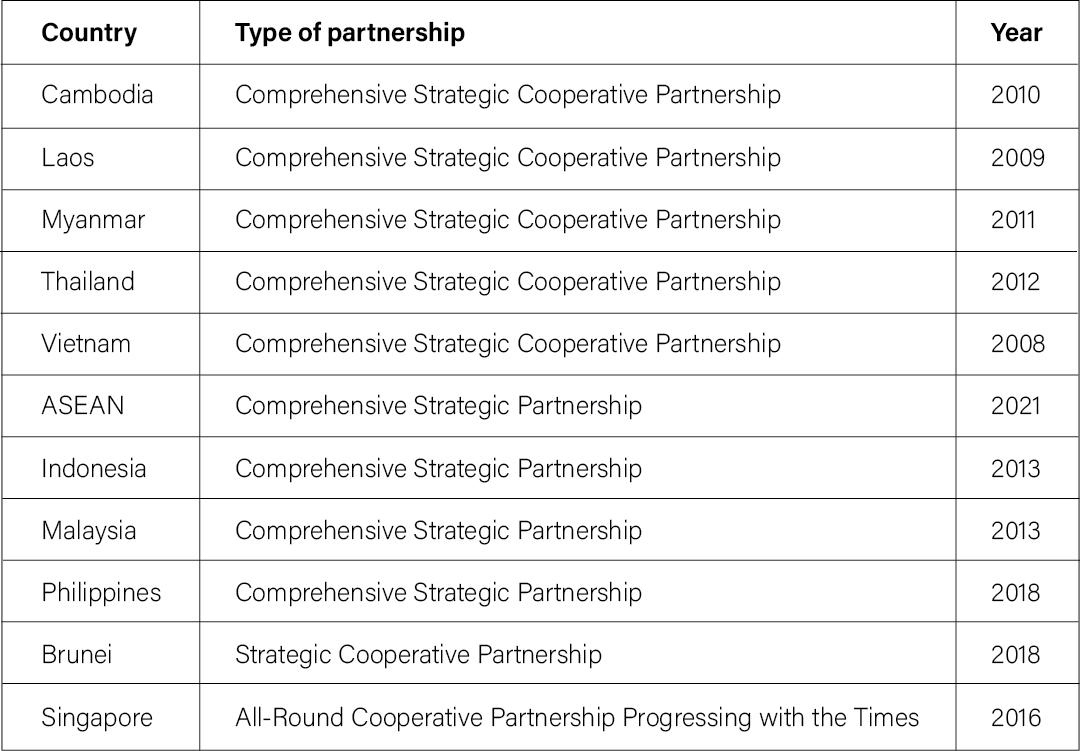

China is the country with the largest diplomatic network in Southeast Asia. It has an embassy in every capital in addition to eleven consulates1. It has established five comprehensive strategic cooperative partnerships, the highest level of China’s diplomatic relations. Notably, in November 2021, ASEAN and China established a comprehensive strategic partnership.

Table 1: China’s diplomatic relations with Southeast Asian nations

Sources: Authors’ own research.

China describes its global partnerships in various ways. As Quan Li and Min Ye note, partnership titles “at a minimum” signal varying degrees of closeness to China, along with the economic and security importance to China of particular countries. “Comprehensive strategic” partnerships have proliferated in recent years but still indicate high priority relationships from a Chinese perspective.

Cultural power

China’s soft power assets in Southeast Asia are considerable. While Confucius Institutes have lost momentum in the West over concerns about foreign influence, censorship, and academic freedom, they have enjoyed more traction in Southeast Asia, where China has established 40 institutes. For example, in Thailand, which hosts twice as many Confucius Institutes than the next largest host in the region (Indonesia), one Institute has been instrumental in helping Senators learn Mandarin and culture through a specific training course in 2018 and 2019.

Another link between China and the region are the 77 sister city pairs. In the Philippines, which has the highest number of sister cities, Chinese cities provided their counterparts with pandemic assistance in 2020.

Chart 1

Chart 2

Tourism

Chinese visitors to ASEAN countries steadily increased in the years leading up to the pandemic. In 2017, the number was just over 25 million and by 2019, it had reached more than 32 million. Total two-way people flows topped 65 million in 2019, according to China. The largest share of Chinese visitors head to Thailand (nearly 11 million in 2019), followed by Vietnam and Singapore, but the Philippines has seen its numbers rapidly increase.

When the pandemic struck, the regional number shrank by a factor of eight to just 4 million total visitors to ASEAN countries in 2020, with a further slump in 2021.

Graph 1

During normal years, there are also a significant number of international students from Southeast Asia studying in China. In 2018, international students from Thailand numbered 28,600, which is the second largest cohort behind South Koreans. Students from Indonesia (15,000), Laos (14,600), and Malaysia (9,500) also made up a significant proportion.

Digital

Digital diplomacy, that is, the use of social media to build China’s global influence, guard the “truth” and correct “misunderstandings,” plays an increasingly important role. In Southeast Asia, a region with young and digitally connected populations, Chinese embassies have established 11 Facebook accounts and two Twitter accounts, in addition to Ambassadors’ accounts. During the pandemic, social media accounts were used to highlight China’s assistance, but also to “amplify spin and outright false messages,” including related to the origin of COVID.

Pandemic diplomacy

Vaccines

China was the first country to deliver vaccines to hard-hit Southeast Asia. By the end of 2021, China had pledged 50 million doses of its inactivated whole virus vaccines – as opposed to mRNA vaccines – to the region, of which 40 million had been delivered. During the November 2021 ASEAN-China Special Summit, Xi pledged an additional 150 million doses of vaccines to ASEAN member states. Of the total global donations coming from China, two thirds went to Asia and four of the five top recipients were in Southeast Asia: Cambodia, Myanmar, Laos, and Vietnam.

Chart 3

Despite being late to the game, by the end of 2021, the United States had overtaken China as the largest vaccine donor to the region. Of the 87 million doses pledged, 74 million had been delivered. Most of those went to Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines.

Japan also emerged as a significant donor, sending greater numbers than China to Indonesia and Vietnam. Of the 25 million doses pledged by Australia, 12 million had been delivered, mainly to Vietnam, Indonesia, and Cambodia by the end of 2021.

Chart 4

Southeast Asian nations had also bought 480 million doses of Chinese vaccines by the end of 2021. More than half of those were bought by Indonesia, followed by the Philippines. Vaccine sales from the United States amounted to 360 million. The Philippines, Singapore, and Malaysia bought at least twice as many vaccines from the United States than from China.

Chart 5

High-level engagement

We calculate at least 100 high-level engagements between China and Southeast Asia across 2020 and 20211. Half of these were in-person while the other half took place via phone or video. Vietnam recorded the highest number of meetings, followed by Indonesia and the Philippines.

Map 1: Bilateral visits and virtual meetings between China and Southeast Asian countries from 1 January 2020 to 31 December 2021 (click to interact)

While he never left China, Xi called his ASEAN counterparts 25 times. He spoke most often to leaders in Vietnam (5), Laos, Myanmar, and Indonesia (4). With Vietnam and Laos, most calls were with the Communist Party General Secretaries. Foreign Minister Wang Yi held the greatest number of meetings – 47 overall with 36 in-person, more than half of which (19) took place in Southeast Asia.

Economic relationship

Trade

The pandemic proved beneficial for China-Southeast Asia trade. In 2020, ASEAN displaced the EU and became China’s top trading partner, which continued in 2021. The strong growth in trade with China was driven by a combination of factors, including China’s success in containing the pandemic in 2020, strong consumer demand – especially in the United States – for electrical and electronics (benefiting Southeast Asian exports to China of components), and lock downs and factory shut-downs in Europe. Higher commodity prices also benefited some ASEAN countries, such as Indonesia.

Within ASEAN, China’s largest bilateral trading partners are Vietnam, Malaysia, and Thailand.

Chart 6

Charts 6 and 7 (below) demonstrate that the increased trade in goods is mainly due to increased activity with China, while trade with the United States, EU, Australia, and Japan has remained relatively consistent since 2019.

Chart 7

Investment

On an ASEAN-wide basis, China’s FDI in Southeast Asia held roughly steady in 2020 before picking up in 2021. China lagged behind the United States in FDI flows in 2020 and 2021. Japanese FDI flows dropped significantly during the pandemic, with China overtaking it in 2021. However, the United States and Japan, as well as the EU, continue to have larger FDI stocks in Southeast Asia than China.

Chart 8

Chart 9

China’s investments and grants in Southeast Asia, as indeed across the world, are often in the form of large infrastructure projects, many of which form part of the BRI. These include high-speed railways in Indonesia and Thailand (see case studies), as well as the Estrella-Pantaleon Bridge in Manila, which opened to the public in July 2021 and which had been financed through a Chinese grant.2

From 2020, many of these investment and construction programs plunged due to the pandemic. Investment recovered only mildly in 2021, while construction has improved more quickly.

Based on forecasting by Baker McKenzie, Southeast Asia will be the second biggest recipient of BRI funding between 2020 and 2030, the biggest being sub-Saharan Africa. Already, four countries in the region (Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam) are among the top ten investment recipients.

Military ties

Another area where the United States leads China is on arms sales to Southeast Asia, although Chinese sales have steadily increased since 2010; Myanmar is China’s largest recipient in Southeast Asia and fifth largest globally. In 2019, China’s military transfers had surpassed those of the United States (markedly visible in its sales to Thailand, see Chart 11), a trend that reverted to a more traditional distribution in 2020 and 2021, when transfers by the United States surpassed those of China. The global downturn in China’s arms exports in 2020 was in part due to the economic fallout of the pandemic.

Chart 10

Of the three case studies, only Thailand receives significant military transfers from China, with the share of Chinese military hardware paling in comparison to that of the United States in the Philippines and Indonesia.

Chart 11

In the early months of the pandemic, China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) engaged in its own type of “mask diplomacy” across Southeast Asia. These military-to-military donations were much smaller in scale than the government-led donations and were also much less publicized. They very clearly aimed at those with whom the PLA wants to deepen ties, including all of Southeast Asia.

Elite perceptions

The 2022 ISEAS survey found that 58 percent of government, business, and civil society elites in Southeast Asia rated China’s vaccine support to the region as the highest. Less than half (23 percent) picked the United States. Australia followed in third place (5 percent).

Positive perceptions of China have not recorded a corresponding lift in trust.

When asked who the region should align with given a binary choice between China and the United States, 57 percent picked the United States and 43 percent China. A small majority (58 percent) have no confidence in China doing “the right thing to contribute to global peace, security, prosperity, and governance,” with only 27 percent expressing confidence.

1 High-ranking Chinese political leaders and officials we tracked are: President Xi Jinping; State Councillor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi; CCP Politburo member Yang Jiechi; Premier Li Keqiang; Defence Minister Wei Fenghe; Assistant Ministers of Foreign Affairs Wu Jianghao and Chen Xiaodong; Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs Luo Zhaohui; Director-General of the Department of Asian Affairs of the Foreign Ministry Liu Jinsong; and Special Envoy of Asian Affairs of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Sun Guoxiang.

2 A second Chinese-funded bridge in Manila, the Binondo-Intramuros Bridge, was inaugurated in April 2022.

China’s Pandemic Diplomacy: A Helicopter View

As the COVID virus spread from China into Southeast Asia, the pandemic could have been a disaster for Beijing’s reputation and influence with regional governments. But China managed to turn the crisis into an opportunity. Circumstances inevitably vary across Southeast Asia’s diversity, but several factors stand out.

First, as it did globally, Beijing launched an intense, well-coordinated propaganda campaign using both traditional and social media, such as Facebook and Twitter1. Beijing’s self-authored portrait was of a nation responding to the global dimensions of the pandemic with the utmost responsibility and care. China was there to help Southeast Asian countries at their time of need, while the United States was not.

China portrayed Southeast Asia as standing shoulder-to-shoulder with it in a shared battle. As early as 11 February 2020, for example, China’s Ambassador to Thailand asserted confidently on social media that “Thailand appreciates and supports China’s stance and action in the fight against the epidemic.” Whether they liked this co-option to China’s narrative or not, regional governments did not publicly demur – there was no finger-pointing about the origins of the pandemic.

Second, as the case studies and other Asia Society Policy Institute analysis show, China’s early support for the region through the provision of medical equipment and, especially, of vaccines was extremely important to Southeast Asia.

China was quick to roll out deliveries of masks and other medical equipment. Specialist medical teams visited the region. And, in December 2020, as developed countries bought up more vaccines than they needed, China began selling and donating much-needed COVID shots across Southeast Asia. In January 2021, Indonesia’s President, Joko Widodo, was famously photographed, sleeve rolled up, receiving his Sinovac dose.

The hard reality for the United States and its close partners is that when Southeast Asia needed vaccines, through late 2020 and the first half of 2021, only China was there to provide them in large numbers.

As one expert we spoke to for this report noted: “China was a global strategic reserve of what the region needed during the pandemic.” And for all the debate about the effectiveness of Chinese vaccines in preventing the spread of COVID, they undoubtedly helped prevent severe illness and saved lives when the region was in need.

Third, while ministers and senior officials from other countries were mostly staying at home, China showed up. Chinese ministers, party officials, and senior diplomats kept up a steady tempo of in-person visits and digital engagement throughout the pandemic.

Fourth, China’s economy was promoted as the answer to Southeast Asia’s economic recovery, a message that resonated strongly with governments across the region. In 2020 and 2021, China’s ability to keep its economy open, along with high demand from the United States and Europe for electronic goods made or assembled in China, helped pave Southeast Asia’s road to recovery. In 2020, for example, ASEAN pipped the EU to become China’s top trading partner (China has for some time been ASEAN’s top trading partner).

In summary, China effectively used its giant economy and industrial base, active diplomacy and its “discourse power,” to advance its interests and sustain its standing in the region. Through 2020 and much of 2021, the United States looked like a bystander in the region when it came to pandemic assistance.

Cambodia is the closest thing China has to client state in Southeast Asia, but Prime Minister Hun Sen could have been speaking for much of the region when he said, in response to criticism that he was leaning too close to Beijing: “If I don’t rely on China, who will I rely on?”

An opportunity not fully realized?

Still, as the case studies and interviews with experts from the region show, if China managed to avert a rupture in its relations with Southeast Asia, it was also not able to capitalize fully on its ability to help with pandemic aid when this was really needed.

Over time, some of the gloss has come off China’s vaccine program. Most Southeast Asian officials are aware that a substantial majority of the Chinese vaccines arriving in Southeast Asia in 2020 and 2021 were purchased, not donated. And the low effectiveness of Chinese vaccines against infection, especially against new variants like Omicron, is now clear, even if they saved lives when it was most needed. Even some of China’s other pandemic aid quietly rankled at times, including pushing hard for visits by Chinese medical teams when in some cases these were not really wanted2.

The vaccine story changed markedly from mid-2021 onwards, when the Biden Administration began pledging huge quantities of mRNA vaccines, with more arriving from the COVAX vaccine sharing initiative. Southeast Asian countries began using Western vaccines as booster shots rather than Chinese vaccines, especially for front-line medical workers.

China’s foreign policy often worked at cross purposes during the pandemic, a function of Beijing pursuing higher priority interests over building goodwill. Notably, as the case studies show, heavy-handedness in asserting China’s maritime claims around the Natuna and Spratly Islands during the pandemic aroused nationalist sentiment in Indonesia and the Philippines and forced government responses, including attempts to increase their maritime presence in disputed areas and setting out their position on the Law of the Sea to the United Nations.

All national foreign policy narratives carry at least some contradictions, but China’s are embedded in Party ideology.

Xi Jinping Thought on Diplomacy highlights concepts such as the community with a shared future for humanity, but also includes “upholding the authority of the [CCP] Central Committee” as its top line and “safeguarding China’s sovereignty, security and development interests with the national core interests as the bottom-line.” China also likely judges that its military might and economic importance to Southeast Asia will continue to constrain regional responses to its often zero-sum pursuit of national interests in the region. In short, Southeast Asia will have to like it or lump it.

Southeast Asian experts interviewed for this report also frequently raised other deeply ingrained constraints on China’s influence in parts of Southeast Asia that no amount of pandemic assistance or economic cooperation could erase. Examples in the case studies include low levels of trust in China (less so in Thailand), concerns about imported Chinese labor, and China’s tendency to over-promise and under-deliver when it comes to investment, especially in infrastructure. In Indonesia and the Philippines, parts of the state system, notably the defence establishment, remain wary of China.

China was able to increase its influence in Indonesia through 2020 and 2021 through active diplomacy, health cooperation made possible by the pandemic, and growing trade and investment. China was also successful in deterring Indonesia from taking a stronger public stance on its assertive maritime activity in Indonesia’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), PLA military expansion, and human rights abuses in Xinjiang.

The case studies suggest China was less able to capitalize on its pandemic diplomacy in the Philippines and Thailand. In Thailand, the pandemic years of 2020 and 2021 were probably neutral in terms of China’s influence building, as China concentrated its efforts elsewhere, including in Indonesia. In the Philippines, domestic and foreign policy choices by the Duterte government suggest China’s success in influencing outcomes diminished somewhat. But this judgement must be seen in the context of already high levels of Chinese influence in both countries and a long-term trend that favors China.

While this report has focused on the pandemic years of 2020 and 2021, it is worth noting that in 2022 “Zero Covid” has emerged as a potential influence-constraining factor for China. Southeast Asia is a significant importer of both finished products and parts and components from China. Lock downs, transport disruptions and shortages have affected Southeast Asian countries and factories. So too with exports, especially fresh produce vulnerable to border delays. China’s inflexible border controls hinder the in-person diplomacy it wielded so effectively in 2020 and 2021, although it is working to bring students back.

Notably, Southeast Asia has not followed China’s path for COVID management. Rather it has gradually opened borders and is learning to live with COVID, buttressed by reasonably high vaccination rates.

China’s influence – what is the trend line?

For now, neither China’s pandemic diplomacy nor its rising influence in Southeast Asia in general has shifted the preference of most Southeast Asian countries to avoid aligning too closely too often with either Beijing or Washington. The objective, as Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong put it in 2020, is to avoid being caught in the middle of major power competition or being forced into “invidious choices.”

Evelyn Goh describes hedging in Southeast Asia as a “fundamentally dynamic strategy,” with regional countries undertaking “constant adjustment to try to achieve the overall effect of equidistance between two competing great powers.” Regional leaders believe they cannot afford to fight with China. But even the “China constrained” countries, as Goh describes them, don’t want to be swallowed whole by Beijing.

Most of the region wants security reassurance from the United States – albeit at Goldilocks levels: not too little and not too much – while benefiting economically from relations with China.

And the case studies in this report highlight examples of Southeast Asian countries both pushing back and accommodating China during the pandemic. Other partners are also important to Southeast Asia as they strive to maintain their autonomy and juggle the great powers, especially Japan and the EU.

How sustainable is this strategy? Much sharper U.S.-China competition is putting it under pressure. So too is the growing values-based divide between China and Russia and a U.S.-led group of democracies that includes the EU, Japan, and Australia.

A vital variable in managing China’s growing influence is the capability and will of regional leaders to keep juggling the major powers and to say “no” to China (and the United States) from time-to-time. Leaders who were very domestically focused, especially in a more populist era, might find this task harder, a point made by several experts from the region interviewed for this report. One interviewee, for example, commented that Thailand was “being sucked into China’s orbit without a plan to deal with it.”

Most pressure on Southeast Asian hedging will come from China itself. China’s advantages in Southeast Asia – its proximity, the sheer gravitational pull of its economy, the connectivity, the priority it attaches to its peripheral diplomacy, and the consistency of its attention (especially to regional elites) – all serve steadily to build presence and influence relative to others, including the United States. This will be more pronounced in mainland Southeast Asia, but will be seen everywhere in the region. Saying “no” to China is hard now, and will get harder.

One Southeast Asian expert we spoke to warned against “strategic fatalism” in the face of rising Chinese influence, arguing that the instinct for autonomy seen in the case studies was sufficiently “automatic and deeply ingrained” to prevent most of the region switching from hedging to band wagoning with China.

Others were less sanguine about the implications of rising Chinese influence. An expert from the Philippines we spoke to, for example, worried that “the space for Southeast Asian agency is slowly closing in.” Another was concerned that Indonesia was “sleepwalking towards vulnerability” and that Indonesian policy makers already instinctively sought to “keep the peace” with China on difficult issues, without China even asking. One expert from Thailand concluded: “China is always here and will be here forever.”

The risk, then, is continued drift into China’s orbit rather than a decisive swing, accompanied by a creeping trend of accommodation of, and deference to, China’s interests that inevitably erodes some sovereignty and autonomy.

The net effect would be not just a China with more influence relative to the United States and its close partners, but a China with stronger veto power over at least some aspects of Southeast Asian domestic and foreign policy. This would extend to limiting Southeast Asia’s cooperation with third parties where China sees this as inimical to its interests.

China routinely, albeit with mixed success, attempts to block such cooperation (for example, its pre-election warnings to the Philippines on relations with the United States, attempts in South China Sea Code of Conduct negotiations to limit the involvement of third parties, and efforts to convince Thailand not to sign up to the Biden Administration’s Indo-Pacific Economic Framework3).

On current trend lines, China’s success rate in deploying its veto power will grow, especially in relation to bilateral and mini-lateral cooperation that China might see as part of a balancing strategy against it, and which acts to dilute its own influence. Examples may include cooperation such as joint naval patrols or other military exercises, and even diplomatic forums such as the Indonesia-India-Australia trilateral.

A China with stronger veto power would have other significant implications. It could, for example, make permanent the divisions already evident in ASEAN on how to deal with issues like China’s pressure in the South China Sea and the coup and brutal civil war in Myanmar. Gaining Southeast Asian support on issues like trade coercion, standards (e.g., 5G) international maritime law, military balancing and the like would be ever harder. And it likely would accelerate the current instinct of the United States to work selectively in Southeast Asia and to work around the region in groups like the Quad and AUKUS.

1 For China’s social media activity in Southeast Asia during the pandemic see https://southeastasiacovid.asiasociety.org/chinese-digital-diplomacy-southeast-asia-pandemic/

2 President Duterte was unlikely to have been concerned, but interviews of experts in the Philippines suggested considerable irritation in parts of government about Chinese medical teams being pushed on Manila, along with “learning from China’s experience” advice that was highly critical of Philippine policy settings.

3 Raised during interviews, but see also https://asiatimes.com/2022/06/china-losing-us-gaining-crucial-ground-in-thailand/

Indonesia: China’s Pandemic Diplomacy Success Story

Introduction

On a typically steamy Javanese evening on Sunday 6 December 2020, the first batch of Sinovac COVID vaccines arrived at Jakarta's Soekarno-Hatta international airport. Camera crews from President Joko Widodo's office were on hand to record the unloading of the cargo. "We are very grateful, Alhamdulillah (praise be to God), the vaccine is available, which means that we can immediately prevent the spread of the COVID-19 outbreak," President Widodo announced.

Tragically, over the months to come, a slow vaccine roll-out program and reluctance to shut down the economy meant Indonesia was not in fact able to contain the pandemic. But, at the time, Indonesia had already ordered 143 million doses of the Sinovac vaccine and China's readiness to provide them when global vaccine supply was being monopolized by wealthy countries appeared a miracle just when one was needed.

Influence-enabling factors

When COVID cases first spread in early 2020, Indonesia quickly turned to its most important trading partner. Starting in March 2020, China donated test kits, personal protective equipment, and masks. Vaccine deliveries from December 2020 allowed the vaccination drive to kick off in January 2021. Conversely, Pfizer vaccines did not start to arrive until August 2021.

As one Indonesian expert told us “the deal with China saved the government’s face.” Indonesia was keen to emphasize China’s assistance despite the share of donated doses representing just one per cent of total vaccine deliveries; the rest were bought1. In part due to the government’s efforts to emphasize the reliability of Chinese vaccines, Indonesia is one of the only countries in the region where trust in Chinese vaccines is as high as in mRNA vaccines.

China’s marketing of its pandemic assistance has been successful, certainly more so than that of the United States. In the 2022 ISEAS poll, taken in late 2021, more than two thirds of regional respondents said China had provided the most vaccine support to ASEAN with the United States a distant second at 14 percent, despite the United States having donated nearly 24 million doses, eight times more than China, by the end of the year.

These warm feelings towards China also translate to other areas. While in 2019, 70 percent had little or no confidence in China doing “the right thing,” by 2021 that had decreased to 51 percent. Looking ahead, a majority (54 percent) believe that Indonesia’s relationship with China will improve.

The bilateral economic relationship also deepened during the pandemic. China is Indonesia’s largest trading partner. The hitherto large trade deficit favoring China has slowly been reducing and was put on a “healthier footing” during the pandemic as Indonesian exports of mineral fuels and oil picked up at the same time as some exporting goods saw significant price increases.

In 2020, China became Indonesia’s second largest foreign direct investor, overtaking Japan. Chinese investment flows rose to US$8.4 billion, while Japan’s fell by 40 percent to US$2.6 billion.

For Indonesia, China’s BRI is regarded by President Widodo as a natural fit for the nation’s infrastructure improvement program. Indonesia is one of the biggest BRI recipients globally in dollar terms; in 2020, it ranked second only after Vietnam and in 2021 it ranked first.

Not all infrastructure projects go off without a hitch, however. China’s flagship BRI project in Indonesia, the Jakarta-Bandung high-speed train, has seen costs blow out. Initially budgeted for US$5.5 billion through a business-to-business model, President Widodo had to issue a decree in September to invest an as yet unknown amount of state funds to manage at least part of the US$1.9 billion in additional costs.

During the pandemic, an intense flurry of diplomatic visits allowed China to increase its ties with the government elite at a time when many Western leaders stayed home. Eighteen high-level meetings took place throughout 2020 and 2021 – more than China conducted with any other country in Southeast Asia.

Influence-constraining factors

Beijing’s efforts to assert maritime rights in the North Natuna Sea, where China’s “nine dash line” intrudes into Indonesia’s EEZ, continued to be a significant irritant in the relationship during the pandemic. During tense stand-offs throughout 2020, for example, the entire government, from President Widodo to the Foreign Ministry and Defence, reacted strongly to China’s maritime presence in the area.

Beijing’s attempts to assert maritime rights in the seas around the Natunas is an example of China pursuing one very high foreign policy priority over capitalising on the goodwill it built with its pandemic aid.

China’s assertiveness is of particular concern to Indonesia’s military, which sees itself as the guardian of national sovereignty, even if it recognizes it cannot afford a clash with the significantly more capable PLA and Chinese Coastguard.

Still, China might have calculated the diplomatic costs ultimately would be both low and manageable, and events in 2021 tended to bear this out. In response to Indonesian oil drilling near the Natuna Islands, China took the unprecedented step of asking Indonesia to halt the project, including through a “threatening” letter and the deployment of Chinese coast guard and survey vessels. Even so, Indonesia decided not to raise the issue publicly as it did in 2020, opting instead to send a discreet counter protest to Beijing.

Some observers link China's pandemic diplomacy to Indonesia's preference for quiet diplomacy on the Natunas. Others add that Indonesia lacks strategic clarity, coherence, and willingness to push back against China’s maritime claims. Combined, this results in Indonesia downplaying incidents and, as one Indonesian expert told us, China not needing to coerce Indonesia into being silent, because Indonesia “just does it.”2

Indonesia’s security ties with the United States continue to be strong and represent a constraining factor on China’s influence. At the height of the tensions over the disputed area, in July 2021, Indonesia joined the U.S.-Australia military exercise Talisman Sabre as an observer. In August, Indonesia held the largest ever military exercise with the United States, reportedly also in the face of Chinese objections.

While Indonesian elite opinion on China is slowly softening (see above), broader public opinion on both China and its ethnic Chinese population appears to be travelling in a different direction. When the pandemic started, many Indonesians were quick to blame China and dubbed it the “Chinese Virus.” Some even called for a fatwa to bar Chinese-Indonesians and Chinese nationals from entering Indonesia and the government’s decision in early 2020 to admit 500 Chinese workers led to protests. A majority (82 percent) continue to see foreign workers as a threat.

While most Indonesians are concerned about internal security issues, more than 70 percent see “instability in the South China Sea” as a critical or important threat, and only 42 percent of the population trust China to act responsibly, down from 60 percent in 2011. Growing concerns about China’s behaviour and declining popular trust make it hard for any government to look like it is getting too close to China, at least publicly, as one Indonesian expert noted.

Conclusion

Indonesia's relations with China during the pandemic exemplify the complex mix of global, regional, and national (including political and cultural) factors that play on China's bilateral engagement across Southeast Asia and that affect both its influence and its ability to turn that influence into outcomes that support China's national interests.

In Indonesia, China was not able fully to grasp the opportunity provided by its pandemic assistance, active in-person diplomacy, elite-level ties, and strengthening economic ties at a time of great Indonesian need. Still, we judge that the combination of these factors gives China a story of net success over the pandemic years of 2020 and 2021. China likely has more influence in Indonesia today than it did before the pandemic.

While public opinion does not seem to have changed in favor of China, elite opinion appears to be slowly warming to China, perhaps reflecting intense Chinese diplomatic efforts. And while there are examples of Indonesian push back against China during the pandemic, there are also significant examples of Indonesia accommodating China by remaining silent on, or downplaying, issues such as Chinese assertiveness in the North Natuna Sea or the human rights abuses against Uyghurs and other minorities.

Another example during the pandemic of Indonesian reluctance to criticize China came following the 2021 AUKUS partnership announcement. In a joint statement, Foreign Ministers Wang Yi and Retno Marsudi expressed serious concerns over proliferation risks from Australia’s proposed nuclear-propelled submarines. In contrast, Indonesia was determinedly silent on China’s rapidly expanding military and reports it is seeking to modernize, and possibly expand, its nuclear arsenal.

1 Calculated based on data received by Bridge Consulting

2 For an analysis of China’s grey zone tactics success in the North Natuna Sea, read Evan Laksmana’s article “Failure to Launch? Indonesia against China’s Grey Zone Tactics”, RSIS, July 12, 2022

Philippines: A Receptive President but Popular and Elite Pushback

Introduction

In April 2020, the Chinese Embassy to the Philippines released a song, complete with lyrics written by the Ambassador, as a tribute to frontline pandemic workers and to highlight Chinese pandemic assistance. The music video features snippets of high-ranking government officials thanking China for its help. As an exercise in soft power, the song (titled "Lisang Dagat” - One Sea), backfired spectacularly. The video generated a huge backlash online, exemplified by one Twitter user calling it “blatant Chinese propaganda for mindless sheep to accept China STEALING the WEST PHILIPPINE SEA!” Within a single day, the video racked up nearly 100,000 dislikes and only 1,000 likes on YouTube. Comments have since been turned off and the number of likes is no longer shown. These public sentiments stood in stark contrast to the Philippines’ staunchly pro-China then President Rodrigo Duterte, who repeatedly highlighted China’s assistance during the pandemic.

In this case study, we briefly examine the factors that constrain and enable Chinese influence in the Philippines. The reaction to "Lisang Dagat” demonstrates that popular sentiment remains one brake on Chinese influence. So too does the caution about China in what one interviewee described as the Philippines’ “strategic class,” especially the armed forces. As it does in Indonesia, China’s often aggressive assertion of its territorial claims in the South China Sea works against Beijing’s broader interests in the Philippines. Still, growing economic and people-to-people ties, along with China’s courting of Philippine elites, are powerful, countervailing forces that build influence.

Influence-enabling factors

China saw some early wins in 2020 but was ultimately unable to sustain this during the course of the pandemic. When the pandemic spread to Southeast Asia, China was the first to offer the Philippines pandemic aid. In addition to the central government, local authorities from the Philippines’ large network of Chinese sister cities (the largest in the region) also donated medical supplies.

The Philippines was also one of five Southeast Asian nations to receive a Chinese medical team, bringing along further donated medical equipment1. Of the twelve-member team, three specialized in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) and the team was to “study how traditional Chinese medicine could be used against COVID-19.” Fifteen months later, the Philippine Ministry of Health would issue the first professional qualification certificate for TCM in the country.

A donation of one million doses of Sinovac allowed the Philippines’ vaccination programme to kick off on 1 March 2021. These early vaccine donations, while small in number given the need, were well received by President Duterte, who had made clear he was “not fond of the products of Westerners.”

However, some within the government complained that China had implied that in exchange for vaccines, it wanted “friendly exchanges in public” rather than “megaphone diplomacy.”

The first vaccines from the United States arrived through COVAX two and a half months after China’s first donations, and by the end of 2021, the United States had donated five times as many doses as China. Amid the population showing a strong preference for mRNA vaccines, Pfizer has since overtaken Sinovac as the most used vaccine.

Duterte’s strong push on Chinese vaccines and other health-related assistance was seen rather sceptically by many Filipinos, according to interviewees. Some told us that the fact that most Chinese vaccines were bought rather than donated negatively affected perceptions of China’s pandemic aid. There was a sense that “the Duterte administration granted favorable treatment to China” and there have been allegations of corruption in the government’s procurement of face masks from Chinese companies.

As it does in Indonesia, China puts considerable effort into courting elites in the Philippines. A number of interviewees noted that under Duterte, the Chinese Embassy had enviable access to the President and his cabinet ministers, especially during the pandemic. This is expected to continue under newly elected President Ferdinand Marcos, as China will seek as close a relationship with Marcos as Xi and Duterte enjoyed, while Marcos will want to tap into Chinese funding to deliver on his promises on getting the Philippine economy back on track.

During the pandemic, China continued to cultivate these elite ties with in-person diplomatic engagements. Thirteen meetings took place at the highest diplomatic levels, including seven in-person. Presidents Xi and Duterte spoke on the phone twice. The most commonly discussed topics were pandemic assistance, the contentious South China Sea issue, and investment opportunities.

China’s economic standing in the Philippines is mixed. When the populist Duterte was elected in 2016, his first destination outside ASEAN was Beijing, where he declared a military and economic “separation” from the United States, the Philippines’ official security partner. Duterte hoped funding could be extracted from China for his ambitious Build! Build! Build! infrastructure program.

Indeed, China became the Philippines’ largest trading partner in 2016 and China is its largest export market, with more than a quarter of exports going to China. However, China is not currently a leading source of FDI flows to the Philippines. Singapore, Japan, and the United States all recorded stronger FDI flows in recent years. Provisional official FDI figures for 2021, for example, show China’s investment plummeted by 94 percent to just US$ 17 million, while Japan’s stood at US$ 581 million and the United States’ at US$ 150 million.

Still, Chinese businesses continued to win major government contracts during the pandemic. In mid-2020, the Philippines’ largest telecom company PLDT launched its 5G mobile service using equipment partly supplied by China's Huawei Technologies. In September 2020, China Construction Second Engineering Bureau, a Chinese contractor, won a US$ 1.2 billion deal to build a subway for Manila's premier business district.

Influence-constraining factors

On a stormy day on 17 February 2020, a Philippines Navy vessel spotted a foreign ship in its EEZ. Upon questioning its status, the ship’s captain responded: "The Chinese government has immutable sovereignty over the South China Sea, its islands and its adjacent waters." The Chinese Navy ship then directed its fire control radar at the Philippine vessel, indicating "hostile intent" according to the Philippine Navy.

The President on the one hand and the Defence and Foreign Ministries on the other took different approaches amid ongoing tensions. Duterte tried to calm the situation, rejecting the Philippines’ powers to counter China in the South China Sea as "inutile": "China is claiming it. We are claiming it. China has the arms. We do not have it. So, it's as simple as that." The Ministries however publicly and strongly called on China to restrain from actions in the area – or, in the words of then Foreign Secretary Teodoro Locsin, to “get the f— out!.”

In 2021, as China’s assertion of its maritime claims intensified, even Duterte hardened his public line. But Duterte’s sense of personal grievance over China’s actions, along with popular anger, likely explain his particular South China Sea diplomacy in 2021, rather than any grand re-alignment of China ties.

Even so, helped in part by its vaccine donations and China’s over-reach, over the same period, the United States has been able to deepen its military alliance. On 30 July 2021, nearly 18 months after first threatening to terminate the Visiting Forces Agreement, Duterte retracted the termination. The decision had been widely unpopular both with senators and the military, which remains staunchly pro-United States and deeply suspicious of China.

In December, the Philippines became the first foreign buyer of the Indian-Russian BrahMos cruise missile. BrahMos provides Manila with its first deterrent capability against China. The source of the missile is also noteworthy, as Indrani Bagchi says: “Buying missiles from India is a strategic statement by Manila.”

Popular opinion constrains China in the Philippines, where a latent sense of racism against the Tsinoy (Chinese Filipinos) and the Chinese community, was reawakened during the early months of the pandemic. In a poll of net trust in 2019, China received the worst score of -33 (rated “bad”), while the United States received an “excellent” score of +72. Australia (+37) and Japan (+35) both received “good” scores. This trust deficit mainly comes from Chinese aggression in the South China Sea, but there is also a perception that Chinese promises for large infrastructure projects have not been forthcoming.

Unlike in Indonesia and Thailand, elite trust in China has decreased during the pandemic. Like the rest of ASEAN, Filipino elites do not want to choose between the United States and China. If they were forced to, however, a clear majority would choose the United States with the gap only widening during the pandemic. Looking ahead, 41 percent believe that the Philippines’ relationship with China will worsen, while 28 percent think it will improve.

Conclusion

The pandemic years of 2020 and 2021 might best be described as a missed opportunity for China in the Philippines, one it was unable to leverage to increase its influence. The aggressive assertion of its claims in the South China Sea pushed even Duterte to lash out. Relations with the United States were pulled back from the brink. Trust in China is low and its pandemic aid does not appear to be widely valued. While trade is strong, Japan is more prominent in delivering infrastructure.

Still, some interviewees argued that while China might not have gained ground during the pandemic, Beijing was still better placed today than it was before Duterte’s presidency, and that further growth in China’s influence was almost unstoppable. Some saw this growth as enabled by a strong streak of pragmatism (if not fatalism) in the Philippines political elite, including new President Marcos, when faced with the large power asymmetry between China and the Philippines.

In his first weeks in office, President Marcos has indicated that he will pursue strategic autonomy by hedging between China and the United States and avoid the wild swings of the Duterte era, including stable relations with Washington. He has promised to uphold the Philippines’ territorial claims in the South China Sea and to speak to China in a “firm voice.” At the same time, he called China the Philippines’ “strongest partner” and foresees bilateral relations shifting into “a higher gear.” With a willingness on both sides, it remains to be seen if China and the Philippines can capitalize on the relationship despite the South China Sea-shaped elephant in the room.2

1 Although we were told that rather than being welcomed, the medical team had been “forced” on Manila, and that criticism by the team of pandemic policy settings in the Philippines had rankled.

2 For an excellent analysis of Marcos’s first weeks in office, read Aaron Jed Rabena’s article “The China Factor and “Bongbong” Marcos’s Foreign Policy”, Fulcrum, July 12, 2022.

Thailand: Chinese Influence Despite Pandemic Inattention and Quiet Hedging

In September of 2021, as doubts about the efficacy of Chinese-made COVID vaccines were being voiced in Thailand, the Chinese Embassy in Bangkok swung into action, posting on its social media accounts a sharp rebuke for those people “belittling and slandering the Chinese vaccine without reason.” The Thai government was also quick to weigh in. Deputy Prime Minister Don Pramudwinai praised China’s pandemic aid and cautioned the public that criticism of Sinovac “hurts the friendly relationship between Thailand and China.”

Pramudwinai’s intervention highlights the importance the Thai government places on maintaining cordial and close relations with China. Indeed, there appear to be fewer structural constraints on the growth of China’s influence in Thailand than in Indonesia and the Philippines, especially under the current military-aligned government. The course of China-Thailand relations during the pandemic is illustrative of these structural forces at work, even as China paid less attention to Thailand than other countries in the region.

Influence-enabling factors

Sino-Thai relations remained close and friendly during the pandemic. The government worked hard to mute any criticisms of China, including on highly-charged issues like China’s dam-building on the Mekong. Thailand has refrained from further repatriation to China of Uyghurs who have sought refuge, but it won’t let this group be re-settled either.

Elite trust in China actually strengthened during the period under review. While in late 2019, only 17 percent believed that China would “do the right thing,” that had more than doubled by late 2021. Conversely, the percentage of those with little or no confidence in China decreased by nearly a quarter from 63 to 48 percent. Looking ahead, 46 percent of Thai elites believe Thailand’s relationship with China will improve, while only 15 percent believe it will worsen.

Anti-China sentiment seems contained for the time being in certain segments of the population, including environmentalists and local residents along the Mekong, as well as anti-government reformists who criticize the government for having “kneeled before Beijing” on certain key issues.

China sold its pandemic assistance well – far better, it would appear, than the United States.

When asked in late 2021, most government, civil society, and business elites rated China’s vaccine assistance to ASEAN the highest (64 percent) with the United States a distant second (26 percent).

China’s pandemic public diplomacy is enormously boosted by what some observers have called the “Sinicization” of Thailand’s media. Chinese soft power is rising at the same time as Thailand’s media freedom is declining. Xinhua News provides translated articles for free to some of Thailand’s most popular and high quality news outlets and there are several memorandums of understanding that allow Thai media to republish content from Chinese news sources for free.

China’s other soft power assets in Thailand are formidable. There are an increasing number of exchanges between the Thai ruling political party and the CCP1. Thailand hosts the greatest number of Confucius Institutes in the region, and it has China’s largest diplomatic presence in Southeast Asia with one Embassy and four Consulates.

Economically, with the tourism market devastated (and still rocked by China’s “Zero COVID” strategy), the Thai government turned to goods trade to partially offset the damage. Bilateral goods trade with China, for example, surged from 2020 to 2021 on the back of post-pandemic demand in China and a weaker Thai baht. Investment data for the pandemic years is not yet fully available, but pre-COVID the trend was clear – in 2019 China’s FDI applications displaced Japan’s for the first time, although the latter remains Thailand’s largest investor.

Chinese technology company Huawei continued to make inroads throughout Thailand. Already leading the way in building out 5G across the Kingdom, Huawei built 20,000 new 5G stations in 2020 and 2021.

Thailand also has the most extensive security ties with China of the three case studies and they are growing. Thailand has annual defence and security talks with China and since 2011 China and Thailand, together with Laos and Myanmar, hold joint patrols on the Mekong. The Thai armed forces are the only Southeast Asian military to hold annual exercises with all three branches of China’s People’s Liberation Army.

While Thailand and the United States jointly hold the annual, multilateral Cobra Gold military exercises, which are much larger scale than its drills with China, Thailand increasingly questions their utility and they have been significantly scaled down since 2004. At Thailand’s invitation, China has been participating in the humanitarian assistance and disaster relief part of the exercise since 2014.

Unlike their counterparts from Indonesia and the Philippines, Thai military officers as a whole do not see China as their biggest threat. They focus on domestic democratic movements and when they think about external threats, they rate the threat from the United States higher than from China. Some interviewees, however, suggested that officers at the operational level tended to be more concerned about China’s actions in the South China Sea and in neighbouring countries like Laos and Cambodia, which could be seen as an “encirclement” of Thailand.

Many want greater engagement with the United States, particularly training. Prior to the pandemic, around twice as many Thai army officers studied in the United States than China, which has a more prestigious course and better career advancement prospects.

Influence-constraining factors

Without the influence-enabling factors described above, the pandemic might have been a period in which China lost momentum in the Kingdom. The diplomatic relationship did not seem to be a priority - only Brunei and Timor-Leste saw fewer high-level bilateral engagements with China than Thailand across 2020 and 20212. The Embassy was headed by a charge d’affaires for a considerable period.

Thailand’s economy suffered a grievous blow from the loss of international tourism, which accounted for 20 per cent of GDP pre-pandemic. In 2019, nearly eleven million Chinese visited Thailand, more than a quarter of Thailand’s total arrivals. In 2021, there were just 13,000 arrivals from China.

The pandemic disrupted other important people-to-people flows. Thai students, for example, have made up the second highest number of international students studying in China, trailing only South Korea. The issue of Thai international students not being able to return to China was a significant diplomatic issue during the pandemic, which Thailand raised on at least two occasions. In October 2021, the Chinese Ambassador promised that Thai students would be “among the first” allowed back once China re-opened its borders.

China’s pandemic assistance to Thailand was smaller than might be expected considering close Sino-Thai ties.

By the end of 2021, the vaccine delivery tally between China and the United States was roughly equal. China had donated 2.8 million doses and sold 45.6 million, while the United States had donated 2.5 million and sold 69 million3.

While China made some progress on the much-delayed and controversial segment of a high-speed rail line between Bangkok and northeastern Thailand4, with the signing of an agreement in October 2020, Thailand continues to drag its feet due to concerns over the terms of the loan. Implementation is moving much too slowly for China’s taste.

Conclusion

China has many advantages in Thailand that help boost its influence relative to the United States and its close partners. Among these are geography, a degree of cultural affinity, soft power, and growing connectivity and economic ties. Thailand’s authoritarian tilt in 2014 also saw it move closer to China, as the country’s ruling generals sought friendly partners and legitimacy for their post-coup managed democracy. Whatever the future for Thai governance – democracy or autocracy – the respected Thai analyst Thitinan Pongsudhirak expects Bangkok’s drift away from the United States to China to continue over the “longer term,” despite the nation’s instinct for preserving strategic autonomy .

These structural advantages carried China through the pandemic, as it does through issues where there are bilateral disagreements and Thailand quietly pushes back. As long as China can manage criticisms over its dams in the Upper Mekong, continue to deepen its security ties despite Thailand’s traditional security relationship with the United States, and remain patient in the face of slow progress on some key issues such as the high-speed railway, nothing stands in the way of an ever-closer relationship.

1 Murray Hiebert, Under Beijing’s Shadow: Southeast Asia’s China Challenge (Rowman and Littlefield, 2020), 282

2 One rumoured explanation for the apparent cooling of the relationship was China’s displeasure at Thailand accepting an expensive renovation of the United States Consulate in Chiang Mai. President Xi Jinping and Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha spoke once on the phone in July 2020 and Foreign Ministers Wang Yi and Dom Pramundwinai met once in Bangkok in October 2020 to discuss Thailand’s vaccine needs, the facilitation of trade and travel during the pandemic, and the Thailand-China Highspeed Railway. They also spoke twice on the phone in early 2021. The only other bilateral engagement was between Minister Pramundwinai and Chinese Assistant Foreign Minister Wu Jianghao via video link for the Fifth China-Thailand Strategic Dialogue. They met again at the sixth Mekong-Lancang Cooperation Foreign Ministers Meeting in Chongqing in June 2021, which the public perceived as a “summoning” by China, according to one interviewee.

3 Calculations based on data provided by Bridge Consulting and the Kaiser Family Foundation.

4 For China, which had hoped the line would reach all the way to Nong Khai Province on the border with Laos, the line represents part of its envisioned "Pan-Asia Railway Network" to connect Kunming in China with countries across Southeast Asia, including Thailand and Laos, all the way to Singapore.

Policy Recommendations

Now and into the future, the United States and close partners like Australia and Japan face some constraining realities in their relations with Southeast Asia.

China’s natural advantages mean its presence in, and influence with, Southeast Asia almost certainly will continue to grow relative to the region’s other major partners. China will continue to give high priority and attention to its periphery diplomacy, which operates within a strong conceptual framework and has clear objectives, as we describe earlier in this report. China’s ultimate goal is a highly connected regional order centred on Beijing in which countries defer to its interests and authority.

China’s diplomacy will often be zero-sum in nature, seeking not just to advance China’s own interests but to diminish or crowd out the influence of others.

Southeast Asia is feeling the pressure of major power competition and is wary of China’s intentions, but still does not want to “choose.” Regional governments worry more about major power contestation than they do about China’s rising influence. Southeast Asia’s major priorities are domestic security and stability and economic growth. The region wants to be valued in its own right, not as a pawn in a new great game with China.