ASPI Climate Action Brief: Bangladesh

By Betty Wang and Meera Gopal

Background

Bangladesh has emerged as one of Asia’s fastest-growing economies since 1971. The country achieved lower-middle-income status in 2015 and is on track to graduate from the United Nations' list of Least Developed Countries by 2026.

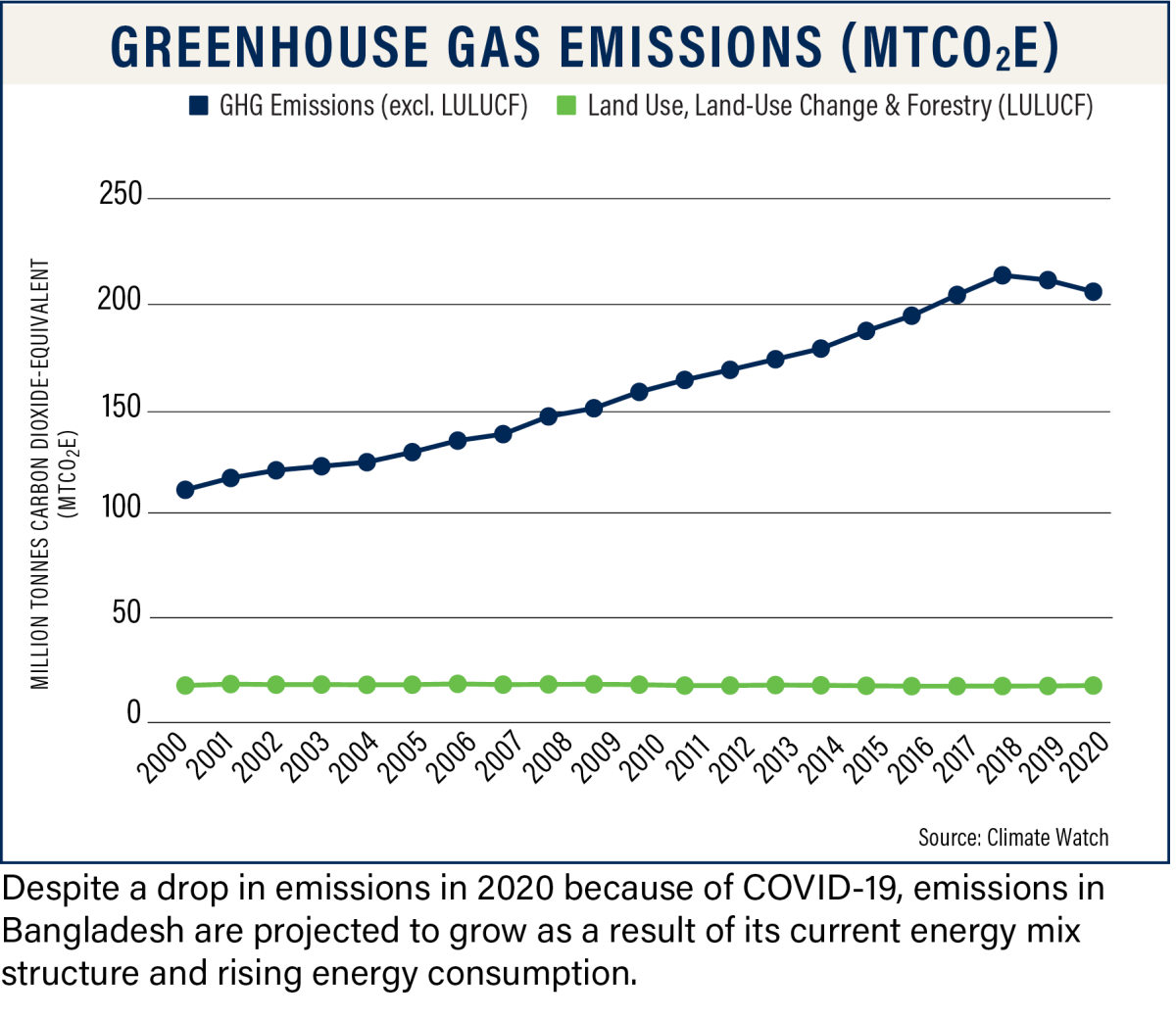

However, this growth has exacerbated Bangladesh's significant environmental challenges. The country's greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions have nearly doubled over the past two decades, although it remains a relatively small emitter on the global stage. Bangladesh's geography is highly susceptible to a range of natural hazards, including cyclones, floods, and dry seasons. The long-term impacts of climate change, such as rising sea levels and increasing global temperatures, pose a severe threat to millions of people along the country's vulnerable coastline. With a high population density, currently ranked ninth in the world, Bangladesh could see as many as 13.3 million people displaced by 2050 as a result of climate change.

Bangladesh has responded to these challenges with proactive climate action. It was one of the first developing countries to establish a coordinated action plan in 2009. The country also set up a Climate Change Trust Fund, allocating $300 million from domestic resources between 2009 and 2012, and in 2014, the country adopted the Climate Fiscal Framework to create climate-inclusive public financial management. Bangladesh also introduced a National Sustainable Development Strategy to further align economic development with climate priorities, and it put forward a target to generate 5% of its electricity from renewable energy sources by 2015 and 10% by 2020.

Ahead of the 21st Conference of the Parties (COP21) in Paris in 2015, Bangladesh submitted its Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC). The country pledged to unconditionally reduce its GHG emissions by 5% from business-as-usual (BAU) levels by 2030 in the power, transport, and industry sectors, and to reduce emissions by 15% with international assistance.

Recent Developments

In a bid to bolster its climate resilience, in 2021, Bangladesh introduced the Bangladesh Delta Plan 2100, a comprehensive development strategy tailored to the country's unique geographical challenges. The Delta Plan aims to eliminate extreme poverty, create job opportunities, and sustain a GDP growth rate above 8% until 2041.

In 2021, Bangladesh also updated its NDC to reduce GHG emissions in all economic sectors by 6.73% below BAU levels by 2030. With international support, it will target an additional reduction of 15.12%, for a total reduction of 21.85%. The Ministry for Power, Energy and Mineral Resources also announced an updated target to increase the share of clean energy in electricity generation to 40% by 2041.

Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has been vocal about Bangladesh's climate crisis on the global stage. At COP26, COP27, and the Climate Ambition Summit, she repeatedly emphasized the need to address loss and damage and called on developed nations to provide adequate financing and technology. During its second tenure as chair of the Climate Vulnerable Forum (CVF) from May 2020 to June 2022, Bangladesh initiated the Mujib Climate Prosperity Plan (MCPP). This plan aims to achieve energy independence through the adoption of renewable energy and energy-efficient technologies while aligning with the CVF vision and the Paris Agreement. More importantly, it sets a strategic investment framework to mobilize finance for renewable energy and climate resilience and sets an example for other vulnerable countries to adopt a similar plan.

In 2022, Bangladesh took another significant step by officially adopting its National Adaptation Plan (NAP). The NAP outlines a financial requirement of $230 billion for full implementation, with plans to mobilize 72.5% of this amount by 2040. As part of this, the plan requests $6 billion per year from international sources.

Reading Between the Lines

Bangladesh has taken significant steps on climate action, including a more ambitious NDC that covers all sectors across the economy. However, the country is still falling short of aligning with a 1.5-degree pathway. According to Climate Analytics, the updated targets would result in a significant increase in emissions — 197% and 149% above 2012 levels by 2030. To align with a 1.5-degree pathway, Bangladesh would need to reduce its emissions by 59-73% below 2012 levels by 2050. Bangladesh has yet to submit a Long-Term Strategy or a net zero goal, which means there is a lack of clarity about its long-term mitigation pathway.

In a significant move to pivot away from high-polluting energy sources, Bangladesh announced the cancellation of 10 coal-fired power plant projects in 2021, recognizing the environmental impact and rising costs in fuel prices. With China announcing its commitment to stop financing coal power overseas, two additional plants backed by China have been canceled since then. At the same time, Bangladesh has been slow to increase its renewable energy capacity. Despite setting ambitious clean energy generation goals, as of the end of 2022, clean energy accounted for only 2% of electricity generation. Thus, Bangladesh has failed to meet both targets established in 2013: to generate 5% of electricity from renewable sources by 2015 and 10% by 2020.

Economically, Bangladesh is grappling with a growing budget deficit and power overcapacity. The government continues to undertake costly development projects, funded through domestic and foreign loans, that exacerbate its budget deficit and put additional strain on the economy. According to a World Bank report, Bangladesh's foreign debt increased from $27.05 billion in 2011 to $91.43 billion in 2021. In the power sector, the installed capacity far exceeds demand, with an overall power system utilization of just 43% for fiscal year 2021–2022. The Bangladesh Power Development Board must pay capacity charges for any power plants that remain idle. Despite this surplus in installed capacity, Bangladesh is still relying on imported electricity, mainly from India, which is cheaper than electricity produced in Bangladesh because of its primary energy crisis. Adding to this dynamic is a new 25-year agreement to continue those imports, commenced in 2023, which will further burden Bangladesh’s foreign exchange reserves.

At the same time, Bangladesh's heavy reliance on imported fuel creates pressure on its energy system. Although the country scrapped several coal expansions in 2021 because of rising import costs, it has shifted its focus to imported liquefied natural gas (LNG) as domestic natural gas reserves become depleted. This increased reliance on imported LNG makes Bangladesh highly susceptible to global energy supply shocks. LNG prices are expected to rise through 2026, a development that could further strain the country's debt and precipitate a long-term energy security problem that exacerbates the country's energy poverty. New policies to shift away from fossil fuels are urgently needed to break this cycle and steer the country toward a more sustainable path.

What to Watch for Next

As Bangladesh continues to grapple with an ongoing energy crisis, exacerbated by extreme weather events and supply shortages resulting from Russia's war in Ukraine, the country stands to gain economically by accelerating its renewable energy capacity and grid connections. According to the MCPP, Bangladesh has the potential to achieve an 80% share of renewables in its electricity mix by 2030, which could result in savings of $2.7 billion by reducing imported LNG costs. This ambitious goal will require strategic investments in new grid systems, strengthening of existing distribution networks, and the introduction of flexible solutions to support the integration of solar energy, while also addressing current issues such as grid inadequacies, the need for more adaptable capacity for variable renewable energy, and the existing oversupply in the electricity market.

Financing remains a critical issue that Bangladesh must address. The country could require an estimated $26.5 billion to meet its goal of generating 40% of electricity from renewables by 2041. While Bangladesh has access to various international funds like the Green Climate Fund, Least Developed Countries Fund, and Adaptation Fund, these resources are currently insufficient to fulfill the country's needs. Bangladesh may look to mobilize additional financing through budget prioritization, carbon taxation, external financing, and private investment. Already, early progress on a carbon tax can be seen in the country's fiscal year 2023–2024 planning for owners of multiple cars. It is estimated that the country could raise $12.5 billion in additional financing for climate action in the medium term.

On the diplomatic front, Bangladesh may continue to position itself as a leader among vulnerable countries in climate mitigation. Under the MCPP model, Bangladesh led the shift away from the prevailing narrative of the CVF of stressing its vulnerability to making itself climate resilient. The country's influence is already evident, as nations like Sri Lanka and Ghana are following in its footsteps and releasing their own plans modeled after the MCPP. Regionally, Bangladesh will likely continue engaging with neighboring countries, particularly India, on energy and water security issues. A looming question is the fate of the 1996 Ganges Water Treaty between Bangladesh and India, which is set to expire in 2026. How the two nations navigate the renewal or modification of this treaty could have far-reaching implications, not just for joint resource governance but also for broader economic and sociopolitical relations between the two countries.

In the lead-up to COP28, Prime Minister Hasina and COP28 President-Designate Dr. Sultan Al Jaber highlighted the need for reforms within international financial institutions and multilateral development banks to draw in more private sector investment. As negotiations for the New Collective Quantified Goal move forward, Bangladesh is advocating for a climate finance target that exceeds the previous $100 billion annual goal and for adaptation finance to double. The country has emphasized that this financing needs to be predominantly grant-based, rather than loan-based, to truly reflect the needs of developing countries facing the direct consequences of climate change. On the sidelines of COP, a collaborative initiative spearheaded by the International Monetary Fund led to the launch of the Bangladesh Climate and Development Platform. The first of its kind in Asia, this new package of measures will act as a Project Preparation Facility to further bolster the country’s mitigation and adaptation finance. In a fitting tribute to Bangladesh’s late climate champion Saleemul Huq, Parties also reached an agreement on the first day of COP28 to operationalize the Loss and Damage Fund, with initial contributions totaling $429 million, while additional pledges continue to be announced as the COP progresses. Bangladesh is expected to continue its key role to advocate for more climate finance delivery to developing nations, including by pushing developed countries to direct new and additional money to the Fund.