Meet the Women of Contemporary Persians

March is Women’s History Month, and this month we will be taking a closer look at the female artists featured in Rebel, Jester, Mystic, Poet: Contemporary Persians—The Mohammed Afkhami Collection. Nine of the exhibition’s twenty-three participating artists are women, and the show was curated by the independent female curator Fereshteh Daftari. The roots of the Afkhami Collection started from the collecting of Mohammed Ali Massoudi and Maryam Massoudi, Mohammed Afkhami’s maternal grandfather and mother. Works in the exhibition examine issues such as gender, religion, and politics with quiet rebellion, sly humor, mysticism, and poetry.

Shiva Ahmadi’s practice borrows from the artistic traditions of Iran and the Middle East to critically examine global political tensions and social concerns. Born in Tehran, Iran in 1975, she grew up during the Iran-Iraq War—a conflict that left a lasting mark on her psyche and art. In 1998, she moved to the United States, where she allowed her own memories of the war to pour into her art, deliberately adopting an exotic language in her drawings, paintings, and sculptures, which are loosely based on Persian traditions of manuscript paintings and elaborate decoration. In her 2010 piece Oil Barrel #13, one in a series of fetishized oil barrels covered in lavish ornamentation, a seemingly bleeding bullet hole alludes to the connection between the logic of war and the lust for oil pursued in distant lands.

Shirin Aliabadi was an artist whose work focused on presenting an image of Iranian women not often portrayed in Western media. With her Miss Hybrid series, begun in 2006, she was inspired by young urbanites who, during the more open atmosphere of the reformist era of the Mohammad Khatami presidency (1997–2005), rebelled against the strict mandates governing the public appearance of women. Staged in the studio, Miss Hybrid 3 features a model wearing a denim jacket, a peroxide-blonde wig, blue contact lenses, and a plastic strip indicating a recent nose job and blowing a bubble with her gum. The work confronts and overturns the sanctioned sartorial codes and even ethnic stereotypes of Iranian women. In Aliabadi’s own words, the societal shift may be characterized as a time when “cultural rebellion meets Christina Aguilera.”

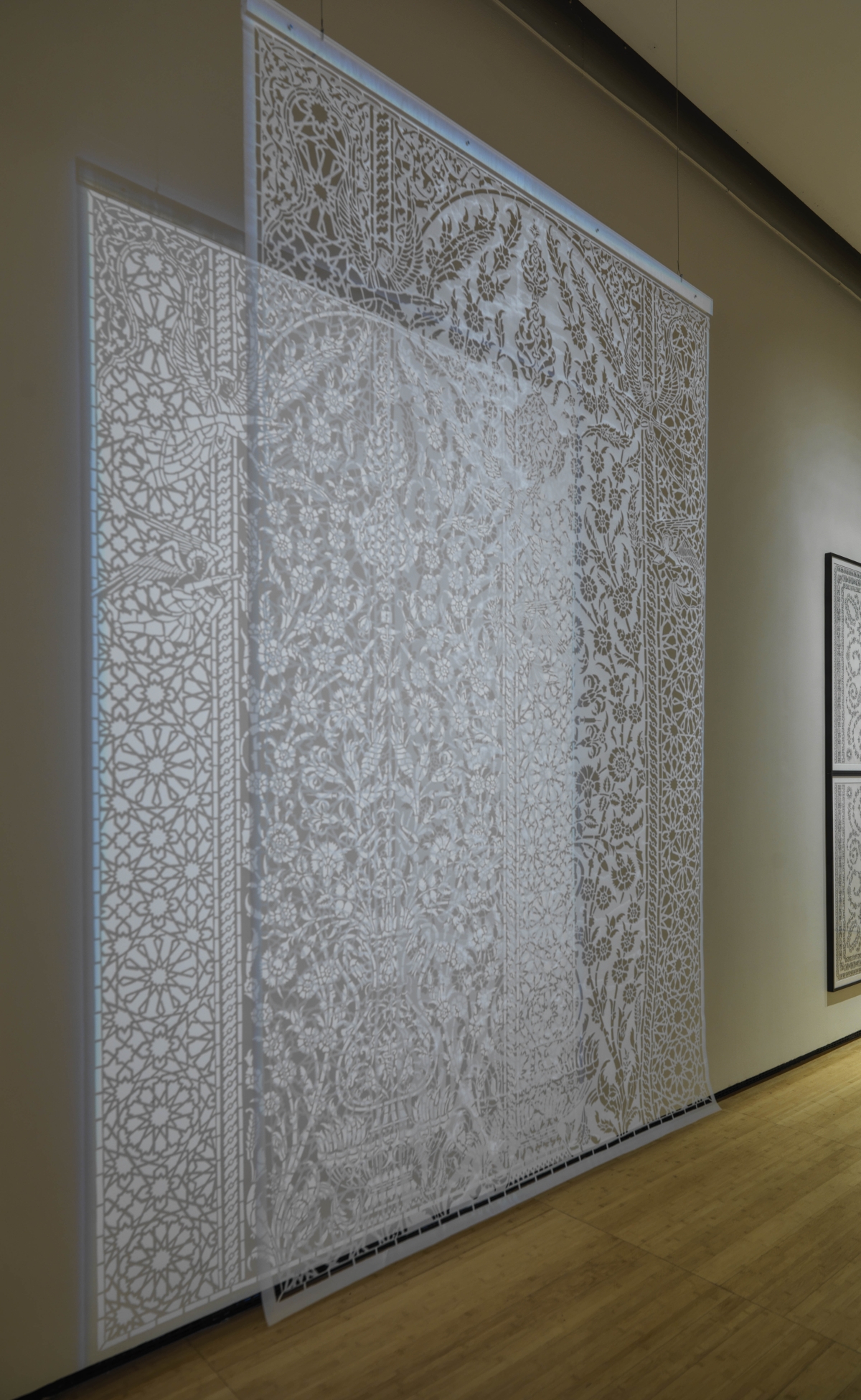

Brooklyn-based artist Afruz Amighi takes inspiration from traditional tilework and carpet designs, translating them through a sly use of new materials and subversive motifs. With Angels in Combat I, she projects light onto a stenciled scrim made from woven polyethylene, an artificial material used by the United Nations to construct tents in refugee camps. At a glance, the overall design, visible as cast shadows, evokes a paradisiacal vision of bountiful vegetation. Closer examination, however, reveals guardian angels turned into executioners, pointing their machine guns at the centrally positioned tree of life. The work takes on a universal dimension by cautioning against any system where life is threatened by the very custodians assigned to safeguard it.

Born and raised in Tehran, Nazgol Ansarinia’s practice reflects upon tensions between private worlds and the wider socioeconomic realm. Ansarinia’s Untitled II is from the artist’s Patterns series, and at a glance, the overall design seems to follow classical arabesques based on plant forms found in traditional carpet designs. A closer examination reveals that the artist subverts tradition by inserting vignettes of everyday urban life such as drummers, athletes, motorcyclists giving rides to wives and children, TV news anchors, housewives lining up for food, and office clerks drinking tea. Most pointed is her inclusion of satellite dishes, the universal means of drawing information from afar, which are sometimes allowed by the regime and at other times are confiscated in contemporary Tehran.

Born in Qazvin, Iran, in 1922, Monir Farmanfarmaian, whose distinguished career spanned more than six decades, was best known for her geometric mirror works inspired by the architectural surface decoration of shrines and palaces in Iran. In The Lady Reappears, Farmanfarmaian’s subject suggests a woman clad in sensual, body-hugging drapery. It is based on an image that the artist, who studied fashion illustration at the Parsons School of Design in New York, found in a fashion magazine. Pointedly, she has cropped the composition so the figure is headless, thus avoiding the need to depict the mandatory headscarf women must wear when appearing in public. Displaying a curvaceously shimmying body in shimmering clothes evokes an ambiguous presence, both tantalizing and ghostly.

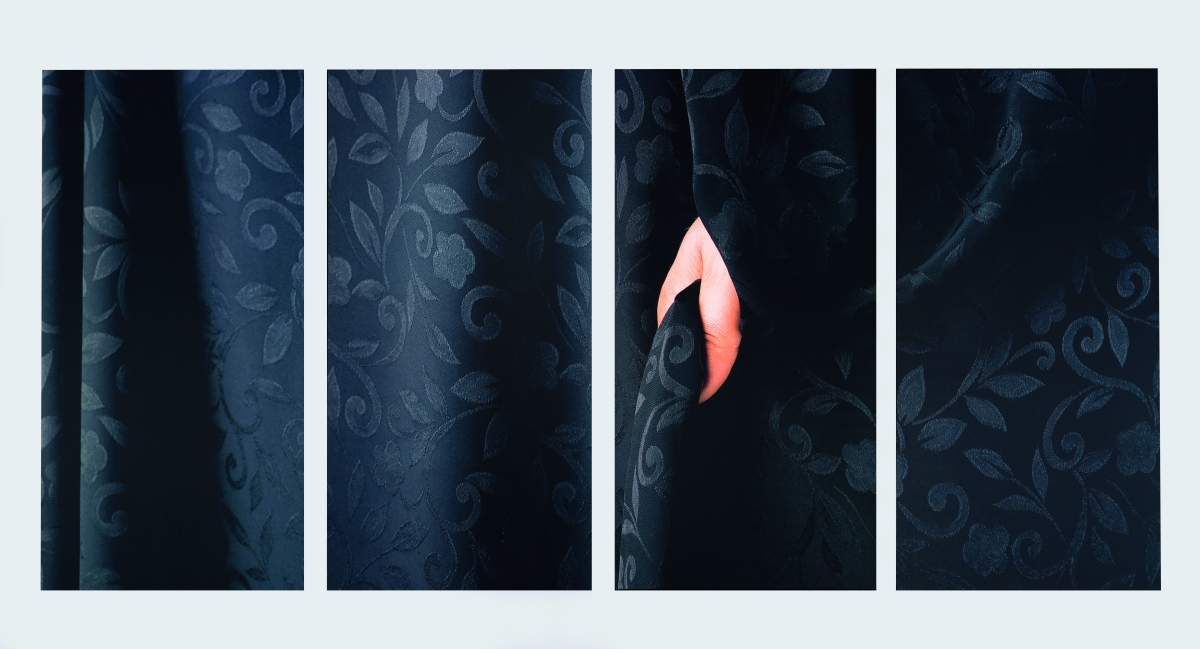

Parastou Forouhar was born in Iran and lives and works in Germany. In this powerful photograph, she addresses both gender and religious politics in contemporary Iran. Titled Friday, (a day of rest and prayer in the Muslim world), this four-panel image is almost completely curtained off with a black swath of fabric, reminiscent of a chador (a cloth veil that covers the head and body); only a clenched hand is revealed. Compensating for prohibitions against the exposed female body, the imagination may meander into forbidden territory, even when the portion of the body on view is only an innocuous hand.

Shadi Ghadirian was born, lives, and works in Tehran. Humor is her weapon of choice in exposing cultural incongruities, past and present. Inspired by photographs from the Qajar period (1781–1925), the artist carefully stages her sitters against a borrowed studio backdrop that emulates a European setting. The historical costumes coexist with anachronistic consumer objects of western derivation and influence. Untitled #10 (left) depicts a woman wearing a protective helmet and riding a Peugeot bicycle. Ghadirian’s photograph alludes to the contradiction that Qajar women may pose with a bicycle in photographs but contemporary women might not be allowed to ride one in public.

Shirazeh Houshiary was born in Iran and lives and works in London. Her work draws on various strains of spirituality, including Sufi mysticism, which she visually communicates through abstraction. In her distinct manner, the abstraction is anchored in and attained through text. In Memory (left), blue pencil markings representing two Arabic words, never decipherable, remain concealed as a silently repeated mantra. With sculptures that fluctuate in form when they are approached from different angles, Houshiary succeeds in conveying a state of flux central to her work and philosophy. Pupa (right), made of translucent Murano glass bricks in a blushing tone, is named after the transformational stage in insects between larva and adult, suggesting the sculpture is in a perpetual state of becoming.

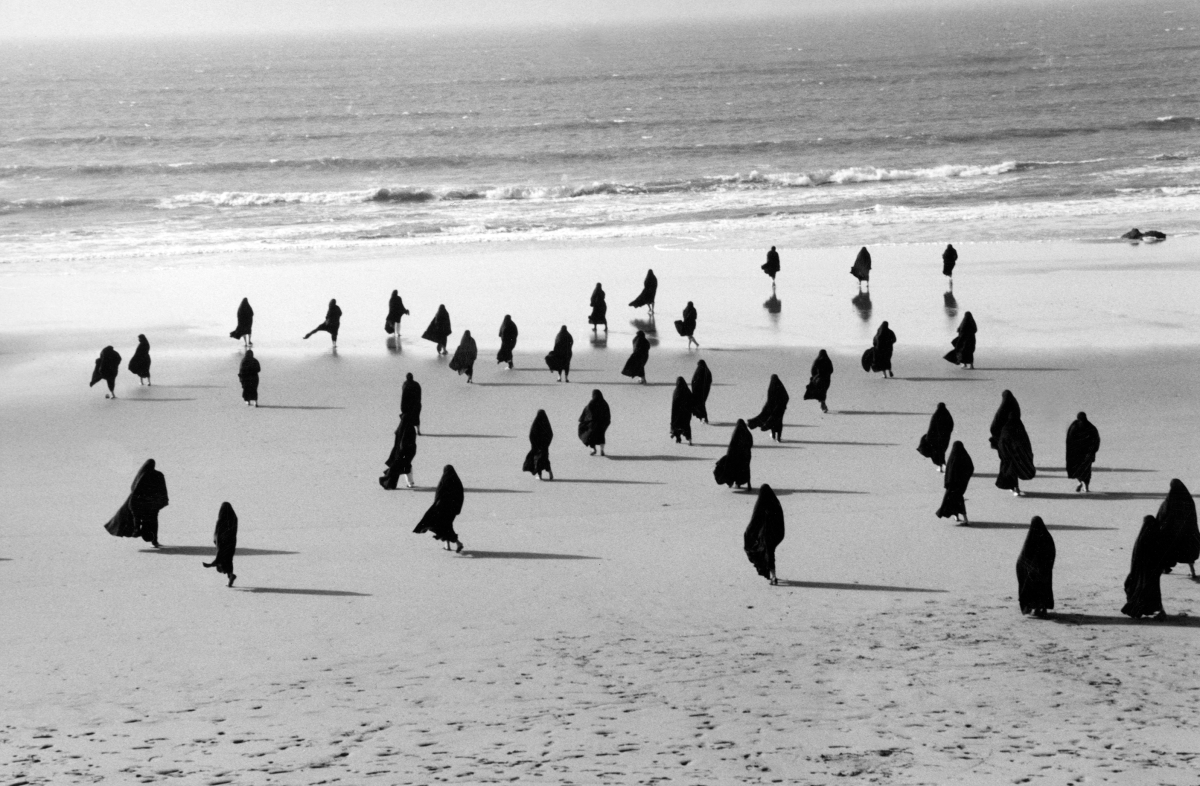

Shirin Neshat was born in Iran and lives and works in New York City. She left the country of her birth in 1975 and did not revisit it except for three short visits in the 1990s. The trips inspired several bodies of work, including her video installation Rapture, which is the source of this untitled photograph. Shot at a beach in Morocco, veiled women, resembling a flock of migrating black birds and acting on a collective will, walk away from their land toward the liberating promise the sea might hold. The image captures the women’s daring rebellion in an evocatively poetic image, far exceeding its small physical dimensions.

Plan Your Visit

725 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10021

212-288-6400