The History of Korean Beauty Part 3: Joseon Dynasty

Following the last two weeks of historical deep dive into the beauty trends of the Silla and Goryeo dynasties, Asia Society Korea presents to you The History of Korean Beauty: Joseon Dynasty as a part of the Leo Gala Series to promote Korean culture and celebrate its beauty beyond the facade.

Ethics during the Joseon Dynasty highlighted virtues like filial piety. In that sense, the Joseon Dynasty marked the epitome of such virtues being preached to and practiced by female members of the family. Virtues were deemed critical to the livelihood of Joseon ladies, wives, and daughters — resulting in a cascade of educational programs and policies that inculcated in women how best to protect their feminine dignity and to uphold their sense of morality. This common understanding of basic virtues was enshrined into the public psyche, creating a common belief that women should carry eunjangdo (은장도), a silver pocket knife, which symbolized a woman’s dedication to protect her moral worth.

Sambaek, samheuk, and samhong

With an emphasis on virtues, elegance and neat appearances became key elements in Joseon’s aesthetic sensibilities. Natural make-up and calm personality became the most prized qualities for Joseon ladies. The three main criteria for feminine beauty were sambaek (삼백;三白), samheuk (삼흑;三黑), and samhong (삼홍;三紅). Sambaek, ‘the three whites,’ highlighted the whiteness of the skin, teeth, and the white of the eye. Samheuk, ‘the three blacks,’ emphasized the need for charcoal-black pupils, eyebrows, and hair. Lastly, samhong, ‘the three reds,’ stressed the redness of the cheeks and lips as well as peachy fingernails. These three elements were directly applied to the embellishment of Joseon women. They wore yeonji, red make-up on their cheeks and lips — and idolized flawless skin much like the modern Korean society today.

Jang Ok-jeong (장옥정), also known as Hui-bin Jang (장희빈), was an exceptional beauty in the Joseon Dynasty who was the only person recorded in the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty about her beautiful features. Jang Ok-jeong worked as a palace maid and King Sukjong (숙종), the 19th King of the Joseon Dynasty, noticed the beautiful Jang around 1680 when she started to serve the King directly. Many viewed the relationship between the king and Jang with trepidation as they feared his deep affection for Jang would impact the royal family. Her life story is one of the most beloved screenplay materials in Korean period dramas, with several adaptations completed in both dramas and cinema over the years. It is worth noting that the actresses who have played the role of Jang Ok-jeong were deemed the most beautiful female stars of their respective generation.

Furthermore, the image of the ideal lady was well reflected in the role of Joseon wives, whereby a woman’s reproductive health and family background were held to the highest esteem. Especially a wife to the first-born son of the family had to be a well-nourished woman with a round face, white skin with no scars or blemishes, and, preferably, luscious hair.

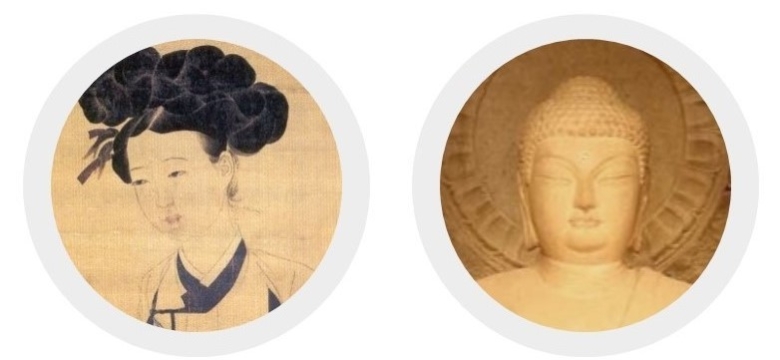

Portrait of a Beauty and the Buddha

One interesting research by a group of physicians and plastic surgeons in Korea concluded that there were striking similarities between the famous Korean painting, Portrait of a Beauty, and the Buddha statues of the Joseon period. The most outstanding commonalities include: 1) ratio of the forehead to face, 2) ratio of the width of the eye to face, 3) ratio of width to height of the eye, and 4) ratio of philtrum to width of the lips. From this observation, we get a glimpse of how the beauty standards of the time were grounded in the Joseon people’s reverence for the Buddha among other things.

Meanwhile, a strict pursuit of femininity as defined by the virtues had a restrictive effect on women’s freedom. As neo-Confucianism became an organizing principle for governing the Joseon Dynasty, there was increasingly heavier emphasis placed on the social fabric over personal choice. It is generally believed that the growth of neo-Confucianism as an underlying ideology led the Joseon Dynasty to be a more paternalistic society even compared to the preceding Goryeo period. The cultural conventions of sexism exacerbated to the point that the term namjonyeobi (남존여비; 男尊女卑), or the idea that men were innately higher in status and thus ought to be more respected than their female counterparts, was frequently used to rationalize their discriminatory practices. This thought was widely disseminated, believed, and practiced by the people of Joseon and formed a crucial part of the Joseon zeitgeist.

Looking back to the beauty trends of the Joseon Dynasty, we conclude that virtues were a currency of people’s everyday livelihood and a central theme in Joseon’s aesthetic sensibilities. Beauty was about pursuing the balance of the outer as well as inner beauty. In this regard, ladies wore natural make-up resembling their bare faces out of a need to protect their virtues. In other words, the beauty standards of the time were not steeped in outward appearances alone. Rather, there was room for people to cultivate the better angels of their nature. The Joseon emphasis on virtues is a mirror reflection of both the beauty of Joseon aesthetics and the blemishes of its social system which heavily suppressed the rights of women. The moral to the story may be that beauty is not just in the eyes of the beholder but also in the balance.