Revelations from the Brush

A Session with a Master Calligrapher

“With a pen, it’s just writing,” explained Dr. Zhou Bin, dipping his brush in ink as he prepared to demonstrate heng, the horizontal stroke. “But with a brush, it’s dancing.” Pressing gently on the thin rice paper with his left fingertips, he anchored his right elbow on the table, and began. The nib alighted with the precision of a ballerina on toe, and hovered before pirouetting abruptly. Transfixed, Zhou's audience watched as his brush landed flat, and, like a tango dancer pulling his partner, dragged a thick line of ink, then snapped back to the left and, grandly lifted off the paper.

Dr. Zhou, a professor at East China Normal University in Shanghai, shares his passion and expertise with people around the world through personal instruction and writing books. He often teaches students who have no background in Chinese, and says calligraphy invites discovery of language, as well as rich cultural and historical contexts.

“Calligraphy builds bridges,” says Ban Ki-moon, Secretary General of the United Nations, who admires this art form’s ability to engage people worldwide. Mr. Ban and his wife regularly practice with Dr. Zhou in sessions that sometimes last eight hours. “Calligraphy is very hard,” Mr. Ban admits in a videotaped session shown by Dr. Zhou; however, he also explains that it is transformative, saying, “Calligraphy brings peace of mind.”

On this day, Dr. Zhou’s pupils were themselves educators, many of Chinese language, and claimed disparate levels of experience. After his presentation, we each positioned ourselves before stacks of gossamer paper delineated with large red grids, lowered our brushes into inkwells, and some halting, others with assurance, began forming lines.

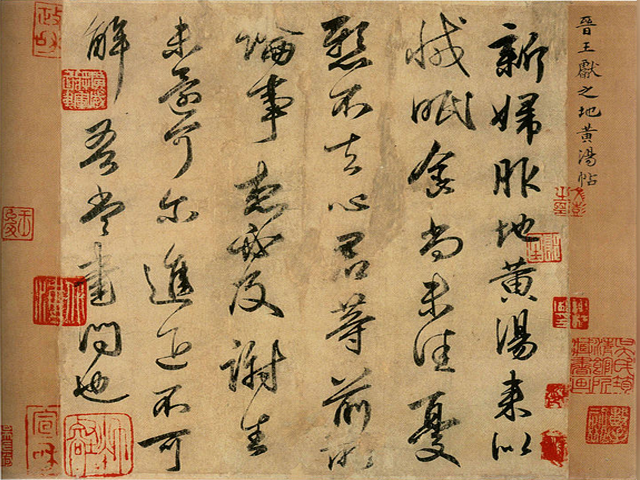

I immediately discovered calligraphy’s lesson in humility. It is one thing to appreciate works of China’s virtuosos, the lingering curves of Huang Tingjian or historic paradigms of Mi Fu, but conjuring my own forms was a shaky undertaking. Each lapse of concentration was indelibly and instantly displayed as the ink soaked into the paper’s fibers. I steeled my resolve, but confidence without experience yields a fleshy, domineering line. No wonder Dr. Zhou also studies psychology, I thought. Calligraphy is a record of the mind, and competence is predicated on a firmness of will, but also a lightness of spirit allowing creativity to flow.

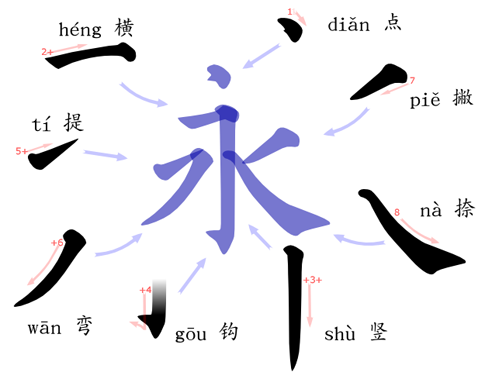

Although I am a novice, there is one definitive piece of advice I can offer to calligraphers at any level: If you are fortunate enough to attend a seminar with Dr. Zhou, procure a seat at the front and offer your paper for demonstration. Then, as you advance through heng, vertical shu, slanted pie and draping na, you can strive to model his strokes. Of these, na is the most difficult, says Dr. Zhou, and initially I agreed . . . until we practiced dian. This modest dot belies the intricate series of brushwork required to give it the contiguous swell and tine.

Leaning back to appraise my work, my deficiencies glared at me. I complained to the teacher next to me that, although I recognized my flaws, I was powerless to alter them. An experienced practitioner, she smiled and observed: “Ah, that is why calligraphy is like life. You cannot go back and fix it; you can only try again.” And so I added philosophical insights to my growing list of revelations through calligraphy.

As I became absorbed in balancing standardized forms with free expression, and endeavored to channel intention into action, I noticed a sensation of wholeness and tranquility. When I viewed my paper again later, I was surprised to find that my critique was milder. The flaws were still evident, but my imperfect strokes were a record of my personal journey across the page. As I visually retraced them, serenity ultimately eclipsed my frustrations.

I then understood why Dr. Zhou spends his time teaching beginners and experts alike. In calligraphy, as with dancing, it is wonderful to watch a virtuoso, but this art form’s true powers lie in the experience.