Radicals Reveal the Order of Chinese Characters

Mastering Chinese is daunting, in large part because learners must memorize thousands of distinct characters. So it is both a revelation and a relief to learners when they discover radicals.

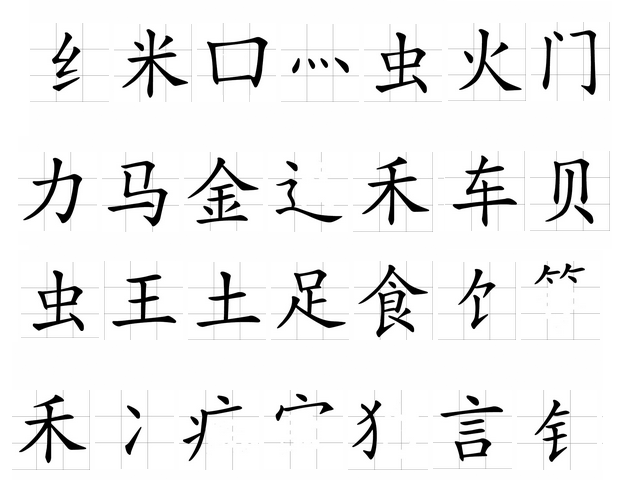

Radicals organize the chaotic swarm of characters into a logical system. Traditional Chinese groups all characters according to 214 radicals (simplified uses 189), which are organized based on number of strokes into a chart called the bushou. Each radical is itself a freestanding character-word, such as one, woman, child, cliff, field, tree, millet, halberd, leather, and bird.

Once inducted into radicals, students can look up characters in a dictionary without knowing the pronunciation. In addition, they can more deeply appreciate the characters they know, guess the meaning of new ones they encounter, and more efficiently memorize them.

For these reasons, Mingquan Wang, senior lecturer and language coordinator of the Chinese program at Tufts University, insists that radicals should be a part of the curriculum for teaching Chinese as a foreign language. “The question is,” he says, “how that should be done.” In spring of 2013, Wang sent an online questionnaire to 60 institutions, including colleges and K–12 schools. Of the 42 that responded, 100 percent agreed that teachers of Chinese language should cover radicals, yet few use a separate book or dedicate a course to radicals, and most simply discuss radicals as they encounter them in textbooks.

Based on the survey results, Wang advocates exploring the benefits of a separate course on radicals, and urges curriculum developers in the field to create new teaching materials and provide training for teachers on how to introduce radicals more deliberately, comprehensively, and systematically. Levente Li, senior consultant at the Confucius Institute E-Learning Center and a visiting scholar at Tufts University, is currently teaching such a class on radicals. He maintains that studying radicals has a value far beyond enabling people to look up characters in a dictionary.

To illustrate this point, Li cites the character 論 (the complex form; its simplified counterpart is 论), which means “to discuss.” The radical on the left is 言, and is itself a free-standing character meaning “speech.” The top right of 論 indicates “to gather” (合) and the bottom section, 冊, means “documents” and derives from a pictograph showing thin bamboo strips tied together, the common medium for written materials until paper became widespread during the Han dynasty (206 BCE–CE 220). Breaking apart 論 in this way converts it from a jumble of fifteen strokes into a logical formation of three elements that is comparatively easy to memorize: talking about a collection of documents means “discuss.” It places the character in relation to others that share the same radical, such as 語 “words” and 訊 “to instruct,” reinforcing recognition and recall. Learning the origin of “documents” adds cultural and historical knowledge.

If the benefits of teaching radicals are apparent, why are courses devoted to them so rare? Weijia Huang, a lecturer of Chinese at Boston University who specializes in the pedagogy of Chinese characters posits, “Even ignoring the level of literacy, or the amount of time for class, there is a lack of materials for advanced study, and so people are unable to teach characters through a special course.”

Huang, speaking in Chinese, agrees that radicals can facilitate the mastery of characters while also building cultural understanding, yet he also encourages teachers to become versed in common inconsistencies. Huang, who has a background in paleography, warns that many characters do not function as a “signific,” a linguistic term indicating a relationship to the word’s meaning. Additionally, the meanings of numerous characters changed over time, or they were “loaned” to other words with separate meanings. Even though more than 86 percent of characters have radicals that also function as significs, Huang encourages teachers to understand some of the exceptions, saying, “It is all right for Chinese teachers not to lecture on these, but they have to know them because students may ask.”

Wang, however, reassures teachers that they need not be pedantic. He notes that Li and Huang are specialists in literary Chinese. “For ordinary teachers of Chinese language, you do not need to memorize these characters with perfect clarity. If you have a book in which you can look them up, that is enough.” Wang has compiled a list of resources to assist teachers with radicals, and hopes that the work of Li and Huang, along with other curriculum developers, teachers, and specialists will further map radicals so that specialized courses can become more widespread, and students can be inducted into the fascinating world of radicals earlier in their studies.