Islamic Iran

Through the Eighteenth Century

An expansive essay on the history of Iran through the first great global age, illustrating periods of economic and political might and as well as periods of weakness and disjunction. Through centuries of foreign assimilation, Iran also retained its distinct cultural identity.

The prophet Muhammad proclaimed the religion of Islam in a series of revelations (which came to be called the Qur’an) that came to him between 611 and his death in 632. He lived in Mecca in western Arabia,and the earliest Mulims or believers in Islam, were Arabs. Motivated at least in part by religion, the Arabs embarked on conquests after Muhammad’s death. Around 636 they defeated the Sasanids and captured Ctesiphon, the capital. The last Sasanid shah died a fugitive in eastern Iran in 651.

The caliphate was the governing institution established by Muhammad’s successors to rule the newly conquered empire. The capital of the caliphate moved from Arabia to Damascus, Syria, in 661 and to Iraq in 750. A new capital was built at Baghdad on the outskirts of the old capitals of Selucia and Ctesiphon. Arab governors sent by the caliphs ruled Iran. Medieval Islamic historians and geographers seldom write about Iran as such; they wrote instead about individual provinces such as Fars and Khuransan. There were many provincial capitals.

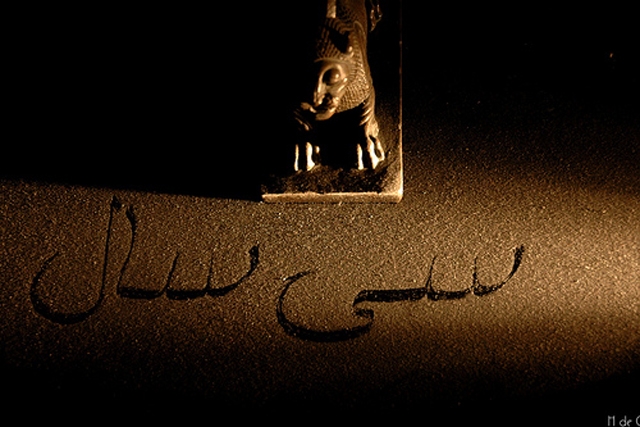

Most Iranians converted to Islam over a period of three centuries. The first generations of Iranian Muslims assimilated the culture of Arab conquerors and did not write in their native language. But from about 800 onward more and more Iranians wrote an Iranian language derived from the Middle Persian languages of the Sasanid period. This language is properly referred to as New Persian or Farsi, although it is usually simply called Persian. It is written in the Arabic script and has a substantial admixture of Arabic loan words. Many Iranians continued to write Arabic, including some of the greatest writers and thinkers in the history of Arabic letters, such as Ibn Sina and al Ghazali.

The literature written in New Persian frequently embodied an Iranian culture tradition that survived the loss of national independence and unity. The Shahnama, an epic poem that recounts the tales of the mythical pre-Achaemenid rules of Iran as well as the historical shahs,was completed Firdausi around 1000. It drew upon poetic sources that were preserved in both written and oral form from the pre-Islamic period.

As the Abbasid caliphate lost power in the ninth century, several Iranian dynasties of different origins arose in various provinces. The major Iranian dynasties were the Tahirids, the Saffarids, the Samanids,and the Buyids. In Baghdad Iranian influence at the count of the caliph steadily increased, until in 945 a Buyid ruler took control of the city.

The Buyid adhered to the Shi’ite form of Islam, which reveres Muhammad’s son-in-law and cousin Ali and his descendants as the divinely appointed leaders of the Islamic community, despite their chronic inability to gain and hold political power. The Buyids retained the Sunni caliphate because the twelfth of the recognized imams, or divinely appointed leaders descended from Ali, had disappeared with a successor a half century earlier. Historians debate the degree to which Iranians adhered to Shi’ism at this time. Written sources indicate that most Iranians were Sunni, but these mostly emanate from the cities. Little is known about small towns and villages.

Prior to the Arab conquests most Iranian cities were small. Iranian aristocrats lived on rural estates and held their wealth ain land and treasure. In the ninth and tenth centuries urbanization on an unprecedented scale changed the character of the country. Numerous cities arose with populations at least in the 50,000–100,000 range(e.g. Nishapur, Rayy, Isfahan, Shiraz). They developed into dynastic manufacturing and cultural centers. A recirculation of wealth from the deposed aristocracy and a centralization of tax collection in the governing centers chosen by the Arbs contributed to this urbanization, as did a migration of converts to Islam from rural or outlying areas.The new cities were predominantly Muslim, and Iran became of the the most influential regions of Muslim intellectual activity.

From around 1000 on the independent Iranian dynasties rapidly gave way to new dynasties of Turkic origin. Turkic peoples have been making slow in roads into Iranian territory for several centuries, but until the late tenth century they mostly remained in Central Asia in a tribal and nomadic society oriented primarily toward horse-breeding. The movement of Turkic tribes in large numbers into Iran is poorly chronicled. Many of the Turks were at least nominally Sunni Muslims, but when and how their conversion came about is obscure.

The Ghaznavids were the first Turkic ruling dynasty in Iran, but they were defeated by the Seljuks and pursued their later history in Afghanistana and India. The rulers at this time usually took the title “sultan,” the Arabic word meaning “power.” The Seljuks established a large empire and brought the rule of the Buyids to an end in 1055. They freed the Abbasid caliph from the Shi’ite control, but they allowed him little more political power than the Buyids had. The Seljuks employed some notable Iranian administrators, of whom Nizam al-Mulk was the most famous.

Family feuding contributed to a rapid decline of Seljuk power in the twelfth century. Iran had been suffering for a century from economic difficulties partly brought on by political disorder an nomadic incursions. Urban populations had been falling because of famine, epidemics, and migration to more prosperous areas. These trends accelerated when nomadic depredations reached a peak in the second half of the century and the dynasty of Khwarazmshahs, established by a lieutenant of one of the Seljuk sultans, proved overly rapacious.

In 1219 Genghis Khan led his Mongol army out of Central Asia and overwhelmed the army of the Khwarazm shah. He conquered eastern Iran and left armies in the west to expand Mongol territory after he withdrew in 1221. The devastations of the Mongols are proverbial, but Iran was already in a deep state of economic and demographic decline before they arrived. The conqueror’s grandson Helegu resumed Mongol expansion westward in a second invasion in the 1250s. He established a separate Mongol state, subordinate to that of the Great Khan in Mongolia, to be ruled by his descendants. This was called the Ilkhan empire, from the title of the rule.

Several of the Ilkhans took steps to rebuild the Iranian economy. Ghazan Khan converted the dynasty to Islam. Their center of rule was in Azerbaijan, the northwestern province, which had seldom played an important role in earlier Iranian history. Eastern Iran, which had flourished in the earlier Islamic centuries, never fully recovered economically or regained political importance. The population of Azerbaijan adopted the Turkic language of the tribes that settled in the region both before and after the Mongol invasion. The Mongol language left little imprint on Iran because few Mongols settled permanently in Ilkhan territory.

The last Ilkahan, Abu Sa’id, died in 1335. Politically, Iran dissolved into regional dynasties of varying origins. Some claimed power in the name of the descendant of Genghis Khan. Others, such as the Sarbadarids in the northeast, based their rule on religion. Sufism, or Islamic mysticism, began to develop into organized brotherhoods, some of which had political ambitions Some Sufi brotherhoods were Sunni, other Shi’ite. The distinction was often unclear, since their emphasis was on emotional religious experience rather than legal structures and definitions.

Timur, known in English as Tamerlane, swept away these petty dynasties in his merciless conquest of Iran in the 1390s. He was a Turkic ruler from Central Asia with an ambition to outdo the incredible conquests of Genghis Khan, one of his ancestors. When he died in 1405 he had subdued every adversary from the Aegean Sea to Delhi and was on his way to attempt the conquest of China.

Timur’s descendants could not hold his empire together. Iran again fell apart among rival petty dynasties. The Akkoyunlu state centered in Azerbaijan was one of the most hereditary leaders of a Sufi order known as the Safaviyya, but they later grew fearful of their popularity with the Turkic tribes. In 1501 Isma’il, the leader of the order, declared himself shah and established the Safavid empire. He relied militarily on Turkic-speaking tribes who wore the red head dress of the order and were therefore called the Kizilbash (“red head”) tribes. Isma’ildeclared Shi’ite Islam the religion of his new state, even though the Safaviyya had at one time been Sunni like most of the Iranian population.

The Safavid empire fought the Ottomans frequently with mixed success. Their wars fixed the Zagros Mountains as the western border of Iran down to the modern times. Safavid power and culture flourished in the early seventeenth century under Shah Abbas I. Isfahan, the capital, became a magnificent showplace. Shah Abbas established a large Armenian community there. Surviving mosques, silks, carpets, and miniature paintings show this to be one of the most creative and flourishing periods in Iranian history.

Iran converted almost entirely to Shi’ism during the Safavid period. Flanked by hostile Sunni states, Iran assumed a national political identity that embodied Shi’ism virtually as part of its definition. Outstanding Shi’ite philosophers and theologians made the period an important one in Islamic intellectual history.

However, administrative and economic problems, combined with rivalries between Turks and Iranians, undermined the empire. By 1722 it was so weak that an army of marauders from Afghanistan was able to take and plunder Isfahan. An able general, who dispensed with the fiction of Safavid rule and himself took the throne as Nadir Shah, rebuilt an ephemeral empire and conquered as far east as Delhi. But Iran rapidly fell apart again after his death in 1747.

The Zand family based in Shiraz was for a while the most powerful political force in Iran, but in the 1780s a family of leaders of the Qajar tribe eclipsed the Zands and established a new unified Iranian state. The Qajar dynasty, which never approached the Safavids in power, wealth or culture, ruled throughout the nineteenth century. The Babiand Baha’i religious movements were the most important social developments of that era. Occasional efforts at reform and westernization, prompted partly by the model of changes taking place in the Ottoman empire and partly by fear of Russian and British encroachment, produced no significant increase in power. By the end of the century the country was weak and in debt to foreign creditors. The shahs were perceived as squanderers of the national wealth.

Author: Richard Bulliet.