Speak clearly to Xi, and avoid the traps

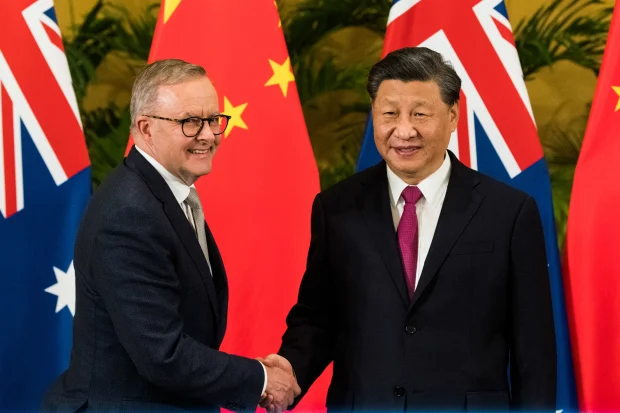

The shadow-boxing around a prime ministerial visit to China has ended. Meeting China’s premier, Li Qiang, in the margins of the East Asia Summit this week, Anthony Albanese said he would visit before the end of the year. The question now is not when to go, but how to go.

In a tough, tense global context, the prime minister’s visit will be watched with interest domestically and among Australia’s close partners for its tone and content.

It’s not easy to get right. China’s authoritarianism, hostility to the West and liberal norms, and aggressive conduct in the Indo-Pacific weigh heavily on the visit.

How, then, to proceed? First, with modest ambition.

The appeal of “stabilisation” lies in its realism about the narrow space for opportunity that now defines Australia-China ties and the differences that separate the two nations. Visiting Beijing is not a moment to pretend otherwise.

Practical steps that advance Australian interests will be sufficient outcomes, such as further progress on trade, pressing for the release of Cheng Lei and Yang Hengjun, and perhaps finding some specific issues on which China and Australia can work co-operatively.

China’s decision to lift punitive tariffs on Australian barley in the face of a losing hand at the World Trade Organisation, for example, adds to the broader stabilisation of bilateral ties since the election and paves the way for a similar outcome on wine.

Beijing sees high-level visits as opportunities to exploit any hint of differences within the West on China.

The Australians Cheng and Yang are detained in harsh circumstances and have no hope of a just outcome without external intervention. The government has pressed hard for their release without any apparent luck to date.

It was reasonable to consider whether the prime minister should go to China in such circumstances. But Beijing appears to have reached the end of its willingness to dole out what it regards as concessions to Australia to enable a prime ministerial visit. A breakthrough may now be more likely through direct leader-level diplomacy in Beijing.

In the meantime, high-level visits from Europe and the United States continue apace. A hard-headed approach to the management of ties with China does not require Australian prime ministers to sit perpetually on the sidelines.

Second, avoid the obvious traps.

Beijing sees high-level visits as opportunities to exploit any hint of differences within the West on China. Xi seeks to split Europe from the United States, Germany and France from Europe, New Zealand from, well, everyone.

China’s leaders use imperial glamour, and sometimes toe-crushing imperial shock and awe, to encourage the required deference to Beijing’s interests. Good preparation makes avoiding this trap easier.

Third, transact the hard issues.

Talking to China in ways that bridge differences is nearly impossible today. In Beijing’s top-down system, a meeting with Xi Jinping might be different, but much depends on the time allocated and whether Xi regards a middle power allied with the United States as worth more than the weary forbearance that seems to characterise much of his international engagement.

In addition to pressing for freedom for Cheng and Yang and for a full normalisation of the trade relationship, the Prime Minister will need to push President Xi on a long list of difficult global issues. Among these are China’s threats to use force against Taiwan, the geopolitical contest in the Pacific, and the imperative of Russia ending its war with Ukraine on just terms.

Fourth, craft a strong public narrative.

While in China, the instinct might be to find only positives to accentuate. Australia has no innate hostility to China, nor does it seek to prevent China’s rise.

For their part, Chinese leaders and officials are fond of saying that there are no reasons why Australia and China can’t get on. Seen from Beijing, China and Australia are not super-power competitors, don’t share a disputed border and don’t have a relationship freighted with historical trauma, as China and Japan do.

But this airbrushes away the many real and potential harms to Australian interests from China’s conduct: Beijing won’t acknowledge these.

The totemic place of China in Labor Party foreign policy has also to be navigated. The prime minister says he will mark the 50th anniversary of Gough Whitlam’s historic 1973 visit to Beijing (making late October-early November one likely window).

Whitlam’s dash to Beijing in 1971 as opposition leader and subsequent recognition of the People’s Republic of China was inspired and paid handsome dividends. It is right to be proud of this history but, in truth, the passage of time also means it bears little relevance to today’s China challenges.

The prime minister is a good communicator on the global stage and will find his own voice in China. Still, continuing as his government has begun, with a tone that that is businesslike, unsentimental, open to opportunity but clear on issues of concern, will work best.

The recent visit to China by the president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, also offers an interesting marker, demonstrating how some European leaders now speak with directness and clarity about the challenges China poses.

Managing differences wisely is a prudent framework, but it is important not to allow China’s narrative that those differences are entirely the fault of the West to go unchallenged, even when visiting Beijing.

This article originally appeared in The Australian Financial Review.