Retracing the money trail to Southeast Asia

By Greg Earl.

Australian companies first made their presence felt in Southeast Asia more than a century ago when tin miners brought significant new capital and technology to the region in a now forgotten pioneering demonstration of successful business engagement.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has described this week’s new Southeast Asia economic strategy as the most significant piece of work Australia has ever done on increasing economic engagement with our closest Asian neighbours. That is true. But there have been quite a lot of these exercises now stretching back to the first such reports by NSW and Victorian trade officials in the early years of Federation.

So, it is unfortunate that this latest large and very comprehensive piece of work doesn’t contain the historical context to make the basic point that Australian investors, inventors and business operators have been here before. What the Prime Minister has rather portentously described as “tied up with national security issues” should not be presented as unknown or uncharted territory, to avoid making it seem even harder to achieve.

Indeed, the tin miners were an example of investment actually entrepreneurially moving ahead of trade in a reversal of the current more cautious approach to Asian business entry. And the flood of Australian manufacturing companies into newly independent Malaysia and surrounding countries in the 1960s underlines how today we are really only rediscovering business opportunities in Southeast Asia.

But the relative economic context has certainly changed. As Invested: Australia’s Southeast Asia Economic Strategy to 2040 says this area “has been one of the fastest-growing global regions, and all its settings – demographics, economic openness, political stability, and ambition – mean it will drive global economic growth through to 2040 and beyond.”

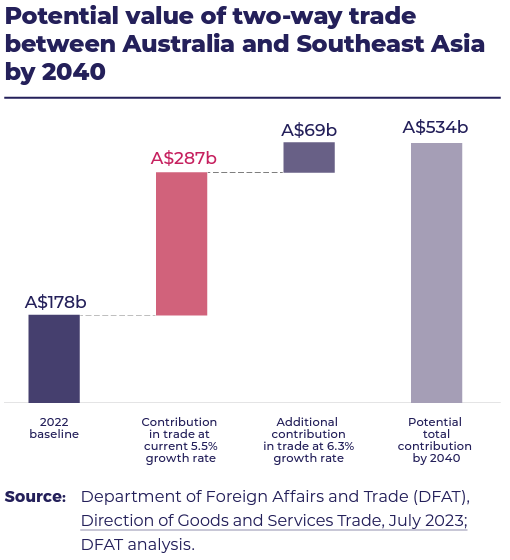

And both sides of the supply/demand equation have also changed. The report argues Australian businesses have never been more globally competitive and capable of providing the goods, services and skills needed in this rapidly growing region, underpinned by Australia’s new capacity for offshore investment particularly from superannuation reserves. Meanwhile Southeast Asia needs new investment including $3 trillion in infrastructure by 2040 and different investment in, for example, renewable energy and modern healthcare.

The government already sees Southeast Asia as the most prospective diversifying option after the tensions with China, as Trade Minister Don Farrell acknowledges in this recent interview.

Four steps ahead

So, what does the latest in a long trail of such efforts say to cut through? The 75 recommendations are quite complex and do repeat some common ground from predecessors such as the 2021 Business Council of Australia/Asia Society Australia A Second Chance study. But they are very usefully organised in a matrix format of short and long-term priorities, and then again in neatly arranged core themes of raising awareness, removing blockages, building capacity, and finally deepening investment. Then they are re-organised across sectors and countries, all of which is critical in such a diverse region of 11 nations.

The report also expands the opportunity horizon beyond the more predictable, narrower remit of this report’s predecessor on business in Indonesia (ie: food, education, health, resources and energy) to new areas such as the visitor economy and creative industries.

It is also striking that this report refrains from using the now familiar Team Australia rubric for doing business in Asia but actually doubles down on the concept with more politically complex and presumably expensive recommendations. It wants National Cabinet rather than the federal government to take on more responsibility for Asian literacy options. It wants to pool private sector and government resources into “deal teams” for identifying and advancing some investment ideas, which the government has immediately endorsed as part of its initial three-point response. And it the report wants to expand the sort of joint investment seen in the Export Finance Australia/Telstra purchase of Digicel Pacific to all of Southeast Asia.

The report takes the increasingly all-embracing concept of statecraft favoured by the Albanese government to a new commercial high with a recommendation that the government underwrite political risk insurance for investment by Australian businesses in what is forecast to be the fourth largest economic zone in the world. This would be a fundamental shift in Australian external economic policy towards the corporatist approaches seen in countries such as Singapore and Japan.

While this project was led by former Macquarie Group chief executive Nicholas Moore, it was produced and published by DFAT, which arguably limits its capacity to publicly deal with some of the sensitive governance issues in the region which are a clear disincentive to many Australian businesses. So, the discussion of the need for government funded risk insurance is relatively circumspect: “One of the most significant risks faced by foreign investors in Southeast Asian countries is disruption of the operations of companies by governance and regulatory uncertainty, including unclear and changing laws and regulations. De-risking mechanisms, such as political risk insurance (PRI), allow investors to share risks – partly or fully – with public agencies whose objectives, experiences and diplomatic leverage enable them to provide PRI cover for countries and projects with higher political risks.”

A super idea for Asia

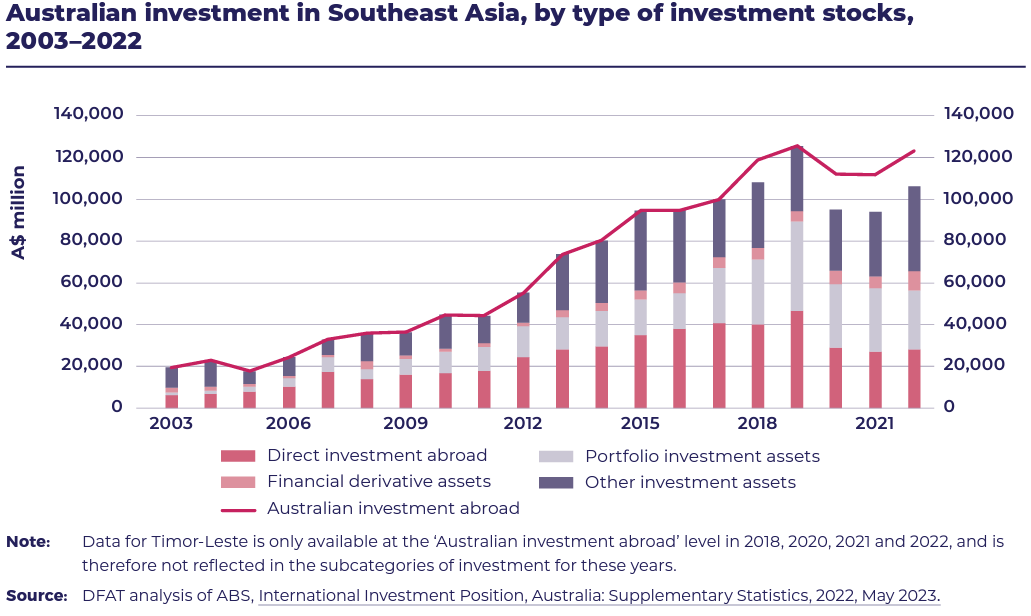

Predictably superannuation funds are seen as the key new players in remedying the lack – indeed decline – of Australian investment in Southeast Asia, as they increasingly are for investment shortfalls domestically. Curiously, despite Moore’s eminent stature as an investment banker, the report doesn’t offer much new insight into the Australian boardroom reluctance to invest in the region.

More refreshingly, alongside the unstated, but souped up, Team Australia approach to getting into Asia, there is also strong support for Australia to be open to more investment and imports from the region. This is presented as both a diversification from too much dependence on the big economies of China and India, but also a mutually beneficial building of greater complementarity with the closer Southeast Asian countries for security as much as economic reasons.

This inward business focus could involve joint promotions by government agencies and business bodies on both sides of potential bilateral trade and investment opportunities, and the exploration of joint approaches to approving investment through fast-track access for pre-approved investors.

It may be diplomatic sensitivity or just analytical uncertainty, but the report doesn’t provide much clear guidance to prospective investors on a key question. Are they ultimately investing in individual countries ranging from Singapore or Indonesia (depending on whether sophistication or size matters) to tiny, isolated Laos or a blossoming global scale integrated economic zone of 687 million people with a US$3.6 trillion GDP, and rising? This is an important issue for investors given the Myanmar conflict has underlined the Association of Southeast Asian Nations’ strategic stalemate while the sparring between Indonesia, Thailand and Malaysia over electric vehicles has underlined the limitations of single market thinking.

Moore emphasises the importance of paying heed to regionalism in his introduction noting: “While the countries of our region are extraordinarily diverse, what unifies them is their keen sense of being neighbours, including the importance they attach to strong regional architecture centred on ASEAN.” The report’s analysis is heavy on regionalism, but its advice veers more towards the nation state with action plans for each country. Indeed, of about 20 actual business case studies, less than a quarter have a pan regional footprint underlining how existing businesses already take a country focus in such a diverse region.

All the way with Australia Inc

After the Defence Strategic Review, the new aid policy and the coordinated international relations spending agenda in the May Budget, this report is now the fourth leg of the government’s “all-in” approach to the region. It declares: “For Australia, an active, whole-of-nation effort will be required to make the most of current and emerging opportunities. If Australia fails in this, it will not be possible to maintain the status quo as the Southeast Asian economies grow relative to the Australian economy, and other competitors intensify their … activities.”

That is all sound, so it will now be up to this government to make its promised public annual review of progress on the outcomes more meaningful than what has followed past exercises like this. Some of the recommendations from a more efficient foreign investment review process to more Asian language study apply equally to other neighbouring countries, so there are questions about how much to create special circumstances for these particular countries. And it remains to be seen whether having Moore as a special envoy can catalyse the recommendations in boardrooms better than has been the case in the past.

Greg Earl edits Asia Society Australia’s Briefing Monthly. He was The Australian Financial Review correspondent in Southeast Asia, an Australia-ASEAN Council board member, and editor of A Second Chance and A Blueprint for Trade and Investment in Indonesia.