The Last Generation: Why China’s Youth Are Deciding Against Having Children

Executive Summary

- The United Nations (UN) predicts that China’s population will start to shrink in 2023. Many provinces are already experiencing negative population growth. UN experts now see China’s population shrinking by 109 million by 2050.

- This demographic trend heightens the risk that China will grow old before it grows rich. It is one of the most pressing long-term challenges facing the Chinese government.

- Aside from the long-term consequences of the One Child Policy, the looming demographic collapse is driven largely by an increasing unwillingness to have children among young Chinese.

- Birthrates are falling across China as young people marry later and struggle to balance their intense careers with creating a family. Many are simply opting out of becoming parents.

- The rising popularity of the DINK (dual income, no kids) lifestyle and uncertainty about the future have influenced many young Chinese to decide against having children.

The Last Generation

The epidemic-prevention workers stand in the doorway of the home of a couple who are refusing to be dragged to a quarantine facility in May 2022, during the infamous Shanghai lockdown. Holding a phone in his hand, the man in the household tells the epidemic workers why he won’t be taken. “I have rights,” he says. The epidemic-prevention workers keep insisting that the couple must go. The conversation escalates. Finally, a man in full hazmat gear, with the characters for “policeman” (警察) emblazoned on his chest, strides forward. “Once you’re punished, this will affect your family for three generations!” he shouts, wagging a finger toward the camera. “We’re the last generation, thank you,” comes the response. The couple slam the door.

This scene, posted online, quickly went viral, and the phrase “the last generation” (最后一代) took the Chinese internet by storm. It captured a growing mood of inertia and hopelessness in the country, one that had been percolating for a number of years but finally boiled over during the COVID-19 pandemic.

That dark mood may be contributing to a key challenge for China: a widespread disinterest in having children. China’s birthrate has declined precipitously in recent years. In 2021, the most recent year for which there is data, 11 provinces fell into negative population growth. From 2017 to 2021, the number of births in Henan, Shandong, Hebei, and other populous provinces dropped more than 40 percent. The United Nations predicts that in 2023, China’s overall population will start to decline. When young people claim that they are the last generation, they are echoing a social reality. Many young people are the last of their family line. This trend is extremely worrying for the government in Beijing, as it sees the oncoming demographic collapse as one of the greatest existential threats facing the country.

In late 2020, Li Jiheng, then China’s minister of civil affairs, warned that “at present, Chinese people are relatively unwilling to have children, the fertility rate has already fallen below the warning line, and population growth has entered into a critical turning point.” Standing at 1.16 in 2021, China’s fertility rate was well below the 2.1 standard for a stable population established by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) — putting China’s rate among the lowest in the world.1

What Is Driving the Decline?

China’s precipitous decline in fertility rate is attributable to a number of factors. The first is the long-term effects of the One Child Policy, which lasted from 1980 through 2016. The dramatic U-turn that the government has taken, from strictly limiting births less than a decade ago to desperately encouraging Chinese women to give birth, has been one of the most stark shifts in government policy of the Xi Jinping era (see the More Child Policy section later in this paper). Historically, birthrates around the world declined as economic growth increased and economies shifted from agrarian subsistence, in which large families are useful as additional labor, to complex and urbanized market economies, in which large families can be burdensome. Part of the decline that China is witnessing is a natural product of its economic development, although the sharpness of the decline and the role that an unbalanced sex ratio plays as a direct result of the One Child Policy cannot be dismissed.

The second driver of China’s declining fertility rate is that young Chinese are marrying later, having fewer children, or forgoing having children altogether (see the section Iron DINK later in this paper). Two statistics make this trend clear. From 2013 to 2020, the number of couples who married in China dropped from 13.469 million to 8.143 million, a decrease of 39.5 percent. Likewise, the average age of first-time parents rose from 24.1 in 1990 to 27.5 in 2020. It is difficult to raise a child in China outside marriage because of government policies that create a legal “gray zone” around single motherhood. As a result, the declining marriage rate is an important factor driving the decline in birthrates in China. The fact that people are having children later also means that they are less likely to have more than one child.

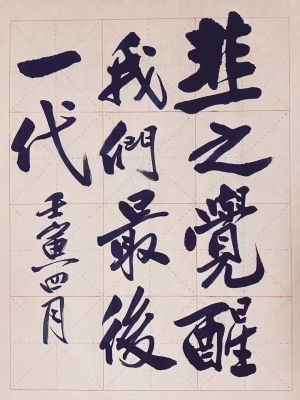

Third, some young Chinese are choosing to not have children as a form of protest. As we have discussed in the previous papers in this series, the future for China’s youth has become increasingly uncertain. As I argued in a recent paper on involution, the sense that people are “spiraling inward” has become pervasive, as young people feel that they are competing intensely for scant rewards in society. This sense manifests in people’s self-description as “chives” (韭菜), an herb that grows back easily after it is cut. The term connotes a sense of complete replaceability and underscores the meaninglessness that many Chinese feel in throwing themselves against the grindstone. The calligraphy above is an example of a recent post aping the Shanghai lockdown video. It reads, “A chive’s awakening; we are the last generation.” Instead of allowing themselves to be cut and regrow, many young Chinese are opting out of the system altogether. By not reproducing, as the government would wish, they feel as if they are taking back a sense of agency. Instead of an endless cycle of being cut and regrowing, they are choosing to let the next chop be the last. To refrain from having children is a form of rupture, an admission that enough is enough.

It is in this wider context of protest that the phrase “the last generation” should be understood. Protest is incredibly dangerous in China: protest leaders regularly disappear, and the sentences for prominent activists are long. Under Xi Jinping, the crackdown on civil society has been severe. Just before the 20th Party Congress in late 2022, a lone protester hung a banner on Sitong Bridge in Beijing calling for an end to lockdowns and the removal of “dictator” Xi Jinping. No one has been able to verify the identity of the protester, who has since disappeared into the maw of the government’s security apparatus. Protests were also seen in many cities after a building caught fire in Urumqi, Xinjiang Province, in late November, killing 10 people. The “white paper” protest that followed saw demonstrations across the country, with thousands amassing on Urumqi Road in Shanghai and some calling for Xi Jinping to step down. However, these protests were quickly shut down by the security forces. Reports alleged that the police were stopping people and inspecting their mobile phones for foreign apps such as Instagram or Twitter, forcing users to delete content related to the protests.

“The last generation” is a much more subtle and resigned form of protest. Rather than take to the streets to rail against the state of affairs and risk losing their precarious social position, many young Chinese are instead marking their unease by refusing to participate in the nation’s future. “China’s zero-COVID policy has led to a zero economy, zero marriages, zero fertility,” said leading Chinese demographer Yi Fuxian. Considering that China’s governing system does not allow much in the way of political participation and strays far from the Western understanding of democracy — despite the claim of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) that it is, in fact, very much a Chinese-style democracy — the choice by young Chinese to not have children can be seen as a kind of plebiscite on social conditions.

Iron DINK

In a recent survey of more than 20,000 people in China, mostly females between the ages of 18 and 31, two-thirds of respondents said they did not desire to have children. As I showed in a previous paper in this series, many young Chinese are torn between the pressure to succeed and the desire to have a family. For example, a popular article published by an online psychotherapy provider had the headline, “My boyfriend was waiting for me at the entrance to my office building, but I chose work.” There is a pervasive sense among young people in China that they cannot have it all. If they want a successful career, they cannot afford to have children, and vice versa.

For many people in China, the cost of living has increased so much that having children is too great a financial burden to seem attainable. The cost of education has risen significantly, and the supply of public kindergartens is seriously inadequate to meet demand. From 1997 to 2020, the proportion of students enrolled in public kindergartens in China dropped from 95 percent to 51 percent. Private kindergarten can cost anywhere from 5,000 yuan (about US$720) to 20,000 yuan a month in Beijing. These costs are just the beginning. An average family living in Shanghai’s affluent Jingan District spends almost 840,000 yuan (about US$120,000) per child from birth through age 15, according to a 2019 Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences report. This includes 510,000 yuan (about US$73,000) on education alone, which is well over half the overall total. In Shanghai’s Jingan and Minhang Districts, low-income families (those with annual incomes under 50,000 yuan) spend more than 70 percent of their total income on the child, the report said.

Setting aside the cost of raising and educating a child, other costs have also increased dramatically. From 1995 to 2021, per capita health care expenditures increased 33 times, far exceeding the nearly 14-fold increase in disposable income over the same period. House prices have also risen rapidly, and with them, the debt burden. From 2004 to 2021, the mortgage-to-income ratio increased from 16.2 percent to 57.4 percent. With housing, health care, and education all increasing at far greater rates than disposable income, it is understandable that many young Chinese would feel unable to support a family. In this sense, what is happening in China is part of a global trend in which young people in many Western cities find themselves unable to get on the property ladder and struggle to support burgeoning childcare costs. This trend is echoed in declining birthrates in many countries, such as South Korea, Japan, the United Kingdom, the United States, and France.

Of course, costs are not the only reason why people are opting out of parenthood. It is important to note that a child can be raised successfully and given the opportunities for a full and flourishing life even without significant material resources. However, the increased costs of having a child mean that for families, the choice also has an important material component.

These costs are changing the nature of work in the country. In China, the stark competition for jobs is a social reality so strong that it is shaping many young people’s life decisions. In 2022, netizens seized on a government document showing that two-thirds of the 131 new civil service recruits in Beijing’s Chaoyang District in April had a master’s or doctoral degree. According to this document, a PhD graduate in particle physics from Peking University would become an urban management officer (城管), a lowly and often reviled post that in previous generations would have been filled by a high school graduate. That someone with such elite credentials would be willing to work such a menial job reflects the wider insecurity experienced by youth in China today. As I noted in the introduction to this series, there has been a 21 percent increase in people taking the postgraduate exam this year, as well as a huge spike in applicants for the civil service exam; there were 46 test takers per vacancy last year. Communist Party membership has also increased.

The stark competition for jobs is also reshaping what is desirable in a potential partner. In 2022, the “office style” or “boyfriend in the system” (体制内男友) became an online trend, as young women posted photos of men dressed plainly as exemplars of what they found attractive. As one online blog post argued, recent history in China has demonstrated that CEOs’ fortunes can disappear overnight, and formerly rich and exciting tech-sector workers are now involuted or unemployed. “At this moment, the ‘iron rice bowl’ of public officials ‘within the system’ is what the heart desires,” the article argued.

Stability has become a determining factor in a person’s desirability, an indication of how unstable the wider society is perceived to be. People are looking to those “within the system” as desirable and future-proof — a demonstration that people are increasingly doubtful of the future. Within this context of doubt, people are increasingly hesitant to have children. While the “office style” might seem like a passing online trend, it helps illuminate the anxieties that are playing out for young people and acting as mitigating factors for them to feel settled enough to have children.

During the research for my PhD, I interviewed one young woman in Chengdu, Sichuan Province, who had chosen to not have a child. As Yujia told me,

"Having a child in China today is too hard. I do not know a single person who has a child and is happy. If they appear that way on Douyin [a popular Chinese social media site] I know they are lying. The reality is awful. The second you are pregnant you have to schedule medical appointments and get a bed in the hospital for delivery. The second you give birth you have to go to a kindergarten to get them accepted for nursery. Then you only have 3 years to get registered for kindergarten (小学). It never ends, the pressure. Then there are the exams the child must take. I am very free and open minded, but I cannot guarantee I would be able to maintain that posture for my child when competition is so incredibly great. There will be 700,000 high school graduates this year from Sichuan province alone. China only has a handful of good universities, so imagine the pressure. How can I be carefree and let my child live as they wish when those are the odds?"

For Yujia, it was not simply the material calculation of how much it might cost to raise a child successfully that put her off. Instead, it was subjecting a child to the brutal competition in society that scared her. She was also worried about the kind of mother she would become in these circumstances. If she would be constantly competing to get her child into the best schools or the best extracurricular activities, how could she not impart those same values to her child? If she didn’t push her child to strive to be the best, was she letting them down? She could not see a way out of this dilemma, and so she decided to just not have a child altogether.

During my research in Chengdu looking at psychological counseling and therapy, I often heard people discuss the concept of dingke (丁克). The first time I heard the term I drew a blank, which my interviewee found amusing. “It’s an English word, you should know it!” they said. Dingke is the Chinese word for DINK, meaning “dual income, no kids.” I had never heard the acronym in English, probably because it is such a common lifestyle choice where I am from that it hardly seems worth commenting on. However, in China, the decision to pursue a dingke lifestyle was still subtly radical and a major topic of discussion online. The dingke thread (丁克吧) on Baidu, one of China’s major search engines, has 73,734 followers and close to 3 million posts.

For most of the year that I knew Yujia in Chengdu, her profile photo on the social media application WeChat was a black square with white text in English: “If you don’t have children your thirties is just your twenties, except you have money.” This phrase encapsulates the decision that many dingke are making. With costs skyrocketing, the choice to not have a child is also a choice to invest in oneself. While some may argue that this decision is a selfish one, it is also a practical choice made in light of the harsh reality of society as it is. “I am not actually just a dingke,” Yujia joked to me, “I am actually a tieding (铁丁),” a resolute “iron dingke.”2

Her choice was not only related to her inability to imagine how to be a mother in a society that she felt was so competitive and costly. “In China, there are too many stories of children dying,” she said, referencing the 2008 poison milk scandal and the Wenchuan earthquake. Though the One Child Policy has been relaxed, scholars have noted that one of the policy’s more dubious legacies is that it has created a society in which single children become the “only hope” of their parents.

Even with the One Child Policy relaxed, so that Yujia and her husband could have multiple children (both are only children), the mentality that the policy has fostered is hard to shake. This explains the rise in discussion of “chicken babies” (鸡娃), who are pushed by their parents to extremes. This trend has been described as “helicopter parenting on steroids.” When Yale University professor Amy Chua wrote her famous book Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mom about pushing her child to get into Harvard, her harsh parenting tactics were derided as sadistic by some Western commentators. However, as Chua has noted in interviews, the book’s reception in China was far more admiring. Instead of seeing the book as a somewhat ironic memoir, parents viewed it as a self-help manual that held clues about how to get their child to the most elite institution in the world. The ends, they argued, more than justified the means. These are precisely the dynamics that have caused Yujia to be so skeptical of having a child.

Half the Sky (or Less)

Another factor that is causing young people to choose to not have children is gender-based discrimination. In recent years, outcomes for women have been worsening. China’s ranking in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index has declined significantly — from 57th out of 139 countries in 2008 to 103rd in 2018. As if to underscore the ruling elite’s lack of concern for the plight of women, the 20th Party Congress in 2022 failed to select a single woman to the Politburo. It was the first time in 25 years that no women were selected for that body.

The year 2022 put the unequal treatment of Chinese women on full display, opening with revelations about a trafficked woman who had been chained in a shack in rural Jiangsu Province. She had given birth to eight children. The country was gripped by the story, as local officials attempted to wriggle their way out of culpability. Then, in the summer, a video of several men beating a group of women who had refused their sexual advances at a barbeque spot in Hebei Province went viral. The central government eventually intervened in both cases, prosecuting the men involved while censoring the wider debate sparked by the incidents. Whereas in other countries — as we have seen, for example, in Iran — these incidents might have caused a feminist uprising, in China, the government deftly managed to tamp down these incidents before they could spark collective action. The tennis player Peng Shuai, who disappeared in 2021 after accusing the powerful Politburo Standing Committee member Zhang Gaoli of sexual assault, remains silenced and out of public view. China’s #MeToo movement remains atomized and stymied by the government.3 Huang Xueqin, one of China’s first #MeToo activists, was imprisoned in 2021.

“Feminism” remains a hotly contested term online in China. As the scholars Angela Xiao Wu and Yige Dong have argued, Chinese feminism, or “C-fem,” as they refer to it, is a heterogenous phenomenon. C-fem leads to class-based critiques from men who see women’s empowerment as challenging to mainstream distributions of power. Popular narratives collapse the various forms of C-fem, characterizing Chinese feminists as hypersexualized and hyperprivileged, and thus open to broad-scale social critique. Feminists are often dismissed in China as “female fists” (女拳, a derogatory term that is a homophone for 女权, or “female rights/power”). Men’s rights activists, who are increasingly vocal in China, often slam vocal women as “feminist whores” (女权婊). “Feminism,” therefore, is a term that is somewhat toxic, and one that women are often wary of adopting.

While engaging in feminist discourse has become a fraught prospect, many Chinese women are instead choosing to respond quietly to their situation by refusing to have children. When the government announced that it would be encouraging women to have multiple children, many women responded online with outrage, saying they felt they were being reduced to “breeding machines.” Many women feel emboldened by the rise of the dingke lifestyle and popular media representations of single women living fulfilled lives. With China’s divorce rate also high — it increased from 26 percent to 53 percent from 2013 to 2020 — many young Chinese women also have strong single female role models they can look to as examples. The party is trying to encourage women to give birth, but without addressing the deeper systemic issues of gender discrimination, this call increasingly rings hollow.

More Child Policy

As political U-turns go, the CCP’s stark shift, from the One Child Policy (1980–2016) to desperately encouraging Chinese women to give birth in the years since, will likely go down in history as one of the world’s most dramatic. Demography is now a key existential issue facing the CCP, as the country risks growing old before it has grown rich. If current trends continue, the size of the labor force will be reduced by 23 percent in 2050 compared to 2020. When the proportion of the elderly population in the United States, Japan, and South Korea reaches 13.5 percent, the per capita gross domestic product (GDP) in each of these countries will be more than US$25,000. In China, which is rapidly approaching this number, GDP is forecast to be only slightly more than US$10,000.

No wonder, then, that Xi Jinping has repeatedly extolled the virtues of families and reinforced his desire that Chinese women give birth. In 2016, he described “wifely virtue” (妻贤) and “motherly kindness” (母慈) as exemplary qualities in Chinese women. Xi has also repeatedly tied traditional family life to being a good citizen: “Loving your family should be like loving your country, every person and every family must make a contribution to the whole family of the Chinese people.”

Along with these lofty words, Xi has instigated a suite of policies to encourage births. Authorities have offered couples several new incentives to have children, including better parental leave, home-purchase subsidies, and a range of other financial incentives. In 2016, with the arrival of the Two Child Policy, China canceled “late wedding leave,” a 30-day paid work leave to encourage marriage after the age of 25. It now hopes that people will marry earlier and have children sooner. Changes to divorce law in recent years also encourage couples to stay together and have children. Couples seeking a divorce must now go through a 30-day “cooling-off period” before they can separate. That change, along with the harsher criteria that are applied when a couple wants to separate, led to a 43 percent drop in divorces in 2021.

State media have begun publishing articles showing that having children young can be a good thing. One such article, “College students have children at school: Most of them do not regret it when they are already two-child mothers,” published by The Paper (澎湃新闻) in 2016, warned that having children late would mean less support from the family: “Late marriage and late childbearing have caused the grandparents to be too old to take care of the child after the child is born.”

More extreme proposals have called for a prohibition of women being able to freeze their eggs. The physician Sun Wei, a delegate to the National People’s Congress, raised this idea at the Two Sessions (两会) in 2020, to encourage people to “marry and reproduce at the appropriate age.” Single men have also been prevented from getting vasectomies, as many hospitals have been directed not to offer the procedure without a “family planning certificate” listing the man’s marital status and number of children. Other facilities require express permission from the man’s partner. One single man chronicled his journey through six hospitals before he was finally able to convince one to perform the procedure.

Still, the government is not willing to encourage births at all costs. Single women who do manage to freeze their eggs find that they are unable to have them inseminated, as they must provide three certificates: their identification card, their marriage certificate, and their zhunshengzheng (准生证) — the “Permission to Give Birth,” which is not granted without the marriage certificate. In general, the legal “gray zone” in which single people find themselves significantly limits the possibility of raising children outside of marriage. LGBT+ couples are not eligible to adopt children or use surrogates, as they are not granted any legal recognition in the country.

This latter point is a blight against the government as it continues to be unsupportive of the LGBT+ community in China, even though this could be a simple win that would encourage more families. If the government believes it is more likely to create stable families by preventing social recognition of the LGBT+ community, then it is misguided. The existence of millions of tongqi (同妻) — straight women married to closeted gay men — shows the unfortunate externalities of suppressing the ability of people to come out and live their fullest lives. Some gay couples in China have managed to subvert family planning rules by using a surrogate abroad and then repatriating the child, but this process is tortuous, requires significant capital, and increases the risk that the government will tighten regulations in the future. The fact that some couples are still willing to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars and years of their lives shows the demand that exists for them to have children.

If the government was not so tight in its definition of a traditional family, it could create the conditions for more births. Single parents are just as likely to raise a successful child as married couples, especially if they are properly supported by the state. Greater tolerance for the LGBT+ community could also be a boon to birthrates. There is an irony here, as one of the long-term consequences of the One Child Policy has been a massive imbalance in the sex ratio in China, as many families sadly chose to abort females, meaning that there are roughly 1.18 men to every woman in China. Given the large size of the population, this means that there are more than 33.5 million more men than women in China. As one netizen wryly pointed out when the latest data were released, “We don’t need to worry about those 30 million. Men can also be together.” As it stands, however, the government is still tightly wed to its understanding of a family as a heterosexual male/female partnership. Therefore, it is only interested in encouraging births within the context of “traditional families.”

Conclusion

When young Chinese talk about being “the last generation,” this should be read as a protest. It is not just a protest against a particular government policy — for example, in opposition to the government’s approach to the pandemic — though this might be true for some. For some young Chinese women, it is a protest against the harshly imbalanced gender dynamics in the country and policies that they feel reduce them to “baby-making machines.” But for the majority of young Chinese people, it is a protest against a growing sense of hopelessness about the future.

In expressing themselves this way, many Chinese share the same sense expressed around the world as inequality skyrockets, the cost of living becomes untenable, and the long-term effects of climate change loom ever greater. As the author Meehan Crist asked searchingly in the London Review of Books, “Is it OK to have a Child?” The fact that this is now a question, and that the biological imperative to propagate could be subject to genuine ethical inquiry, says a lot about how attitudes toward parenthood have changed globally.

The Chinese government’s heavy-handed approach to encouraging births risks further alienating many Chinese women, who already feel as if the country’s gender dynamics are extremely unequal and only likely to get worse as Xi Jinping’s tenure continues. The lack of female representation in the Politburo augurs badly for the future in this regard. If the government is serious about increasing birthrates, it should not try to do so by creating impediments to women freezing their eggs or by preventing men from getting vasectomies. It should also be extremely careful about policies that could be read as reducing women to stereotypical gender roles. Instead, it should consider policies that allow for the flourishing of nontraditional families and make sure that it fulfills its promises to provide a better life for its people. Only when young people believe their futures are secure will they be willing to bring children into that world.

Notes

1 According to the OECD, “The total fertility rate in a specific year is defined as the total number of children that would be born to each woman if she were to live to the end of her child-bearing years and give birth to children in alignment with the prevailing age-specific fertility rates.”

2 This is also a pun, as tieding (铁定) means “resolute.”

3 The #MeToo movement is sometimes referred to in China as #RiceRabbit (#米兔, pronounced “mi tu”) because of the homophonic nature of the characters.