Involution: The Generation Turning Inward and Away From Xi’s Chinese Dream

Summary

- In a time of stark inequality and stalling economic growth, young Chinese feel they are struggling to keep up. In recent years, a new discourse has taken hold in Chinese society. Phrases like “involution” and “lying flat” have become shorthand for a sense that what is required to live an adequate life has become unattainable or unsustainable.

- High rates of youth unemployment and poor prospects for university graduates mean that competition for scarce jobs is extremely intense, with those who find work often exploited by employers safe in the knowledge that they can easily replace burned-out employees. This discourse belies a sense of resignation amongst young people who are increasingly anxious about their future.

- Involution is the result of decades of uneven and unequal development. Young Chinese today face a much more precarious economy, due both to domestic policy reasons and an increasingly unstable international environment. The same means of wealth creation available to previous generations are no longer as accessible. These intergenerational dynamics entrench inequality and a pervasive sense of futility among the young.

- The government is increasingly worried about the level of disquiet amongst young people, with Xi Jinping himself making statements about the continued need for “struggle” and determination. Struggle, a term that resonates with the revolutionary fervor of the Mao era, is increasingly being set up as the official counterpoint to involution.

Turning Inwards

“Involution” (内卷化) has taken the Chinese internet by storm in the last two years, becoming one of the most commonly used terms online in 2020. It implies a growing sense of futility that many young Chinese feel as they struggle to succeed in conditions of increasing economic precarity. As unemployment has become a significant problem in Chinese society, with close to one in five young Chinese now unemployed, competition for scarce jobs has compounded. Instead of perpetuating a system that many feel is unable to reward them despite their efforts, a growing number of people are openly discussing dropping out, “lying flat” (躺平) or “letting it rot” (摆烂). This kind of discourse is percolating to create a normative atmosphere of disquiet, serving to undermine government rhetoric about the successes of single-party rule. Such discourse is therefore now receiving significant attention from official media, with leader Xi Jinping arguing for the continued need for “struggle” and the importance of hard work. His “Common Prosperity” campaign has also been launched and portrayed as a way to attempt to redress some of the entrenched inequality exacerbating involution. It remains to be seen whether this top-down approach will be effective, or whether it might end up further strangling the economy, only making the situation worse.

Involution has its roots as a relatively obscure anthropological term, usually attributed to the scholar Clifford Geertz, whose original research focused on rural Java.1 There he noted that despite increased agricultural sophistication and labor input, the economy remained stagnant. In essence, the excess output from farms was eaten by the laborers brought in to increase production. This created a crushing spiral, in which no matter how much increased effort was expended, the economy remained in stasis. Involution’s emergence in the context of contemporary China now defines a particular form of stagnation within modern urban culture. It captures a sense of wheels spinning in mud; no matter how hard one pushes on the accelerator, there is no forward momentum. Involution’s literal translation in Chinese is “to spiral inwards.”

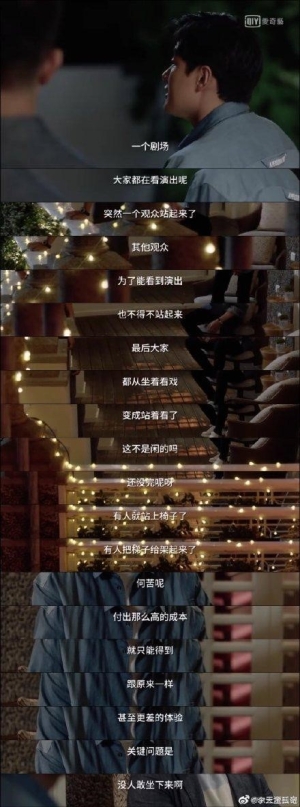

In April 2021, the hashtag “how to explain involution” (#如何解释内眷) became a trending topic on Weibo, garnering hundreds of millions of views within a few days. Chief among those explanations was a scene from the TV drama A Love for Dilemma 《小舍得》, which is about parents struggling to raise their children. In the scene, two fathers speak of the education system: “It is like being in a cinema,” one says, “and someone stands up. To see the film the people behind stand up. Soon the entire theater is standing to watch the film. Then some people stand on the seats. Some go far enough to even grab ladders. The film is the same; all that has changed is that now everyone is uncomfortable.”

To extend the metaphor, today increasing numbers of people aren’t even able to make it into the theatre. China’s youth unemployment rate hovered around 19% or higher throughout most of 2022. The sense that it is increasingly difficult to achieve a good life in the country is underscored by a new social and economic reality that sees many young people unable to find adequate employment. Young Chinese today face a much more precarious economy, both due to domestic policy reasons, including the continued pursuit of harsh epidemic prevention policies, and an increasingly unstable international environment, which means the same means of wealth creation available to previous generations are no longer as accessible. While there are parallels to the “rat race” as experienced elsewhere, there are also significant domestic conditions which make involution a phenomenon quite particular to this moment in Chinese history.

Inequality and Involution

When Deng Xiaoping accelerated economic reforms after Mao Zedong’s death, he conceded that it would be necessary to “let some people get rich first” (让一部分人先富起来). These reforms constituted the largest poverty alleviation program in human history, with 850 million people lifting themselves from poverty, and average life expectancy increasing by over a decade. They also cemented inequality, however. The days of the Mao era, in which society was largely equal because everybody had close to nothing, were soon replaced by spiraling inequality. As the author Yu Hua has noted, society quickly shifted from being told to never forget class struggle to being told to get rich, recreating the class structure that the Communists had railed against. Worse, during the reform period, proximity to the ruling elite became a pathway to phenomenal wealth. The structure of the reforms, which involved selling off state assets into private hands and building vast swaths of new infrastructure, created the perfect conditions for striking levels of corruption.

By 2012, when Xi Jinping took office, inequality and corruption had become existential threats to the Chinese Communist Party. In the preceding decade, under his predecessor Hu Jintao, China’s GINI coefficient (measuring economic inequality) had risen to 43.7, well over the threshold that the UN recognizes as typically creating the potential for social unrest. There were widespread protests around the country, with as many as 180,000 mass incidents occurring per year, or roughly 500 a day.2 As Xi said in his very first speech in office, “there are many pressing problems within the party that need to be resolved. The problems among the party members and cadres of corruption, taking bribes, being out of touch with the people, undue emphasis on formalities and bureaucracy must be addressed with great efforts. The whole party must be vigilant against them."

Xi had very little tolerance for the “loose and soft” governing style of his predecessor. He initiated a massive anti-corruption campaign, which to date has seen nearly 4 million communist party members investigated, including high-ranking officials that had previously been seen as untouchable.

While the anti-corruption campaign has been broadly popular with the average Chinese, inequality is a stubborn social phenomenon. The GINI coefficient in China started to decline in 2013, but it still remains around 38, making China roughly as unequal as Malawi or Indonesia. The fact that some people “got rich first” has meant they continue to benefit from their amassed wealth and enjoy embedded advantages over their less wealthy peers. They have real estate and other assets, social status, and, crucially, are able to buy greater opportunities for their children, compounding inequality into the future.

The reality is that in China the poor are desperately poor. Despite Xi Jinping’s declaration of victory over absolute poverty in 2021, there are still hundreds of millions of people who barely eek out an existence on the margins of society. This was underscored by a video that went viral on Duoyin (the Chinese equivalent of TikTok) that shows a 52-year-old migrant laborer in Zhengzhou, the capital of Henan province. In the video, he is interviewed about his life, and tells the filmmaker that he normally eats only one meal per day, two hard buns (馍) and some water. When he needs a treat, he adds some sugar to his water. That week he had only found one job to do, which meant he had earned only 200 RMB ($30). He was living under a bridge with other migrant workers, all middle-aged. “There are even a few over the age of 60,” he says to the cameraman. He has two children that he is trying to support. The video underscores the fact that there are still scant safety nets in China, and that the disparity between the haves and the have nots now gapes wide.

The growth model that China pursued over the past four decades was always understood to be temporary. Growth rates in the double digits, sustained over a number of years, were the result of technological catch-up, infrastructure development, and the unleashing of the Chinese people to lift themselves from poverty through their own incredible efforts. As the scholar Yuen Yuen Ang argues in her book China’s Gilded Age, corruption acted like a steroid during this period, creating enormous growth but also inducing some nasty side-effects, including environmental degradation and social stratification. It also contributed to a general belief that society was rigged. This laid the foundations for the current ennui that is characterized by involution, as average people came to believe that they will never catch up to the elite, no matter how hard they work.

It may have been inevitable that growth rates would decline over time as this model produced diminishing returns, but Xi’s decision to crack down on corruption and his moves to rebalance the economy have added additional impediments to growth. China still identifies as a socialist polity, and its constitution defines the “principal contradiction” in society in Marxist terms. This is essentially the most pressing issue that must be resolved, according to a dialectical materialist understanding of social dynamics. In 2017, Xi shifted the contradiction from "the ever-growing material and cultural needs of the people versus backward social production," to the “contradiction between unbalanced and inadequate development and the people's ever-growing needs for a better life." The initial contradiction highlighted that the economy did not meet the needs of the people (in terms of growth); Xi amended it to suggest that while it had successfully met most people’s basic needs, it did so more effectively for a small group of elites at the expense of the poor. It was therefore clear that his anti-corruption campaign had fallen short of solving inequality, and a more sweeping policy was needed. Soon, he ushered in his Common Prosperity (共同富裕) campaign. The term has floated in official discourse since the 1950s, as David Brandurski of the China Media Project notes, but in the early reform period it was directly linked to Deng’s notion of letting some people get rich first. As Brandurski shows, a 1979 People’s Daily bore the headline “A Few Getting Rich First and Common Prosperity'' (一部分先富裕和共同富裕), which linked wide-scale growth to allowing some inequality. Under Xi, the campaign has portended a broad restructuring of the economy to reprioritize common prosperity, sending shockwaves through private enterprise.

As Dr. Ang notes in her book, in the United States the gilded age in time brought about the progressive era, in which social instability was quelled with redistributive policies, a huge expansion of civil society, and greater protections for individual liberty. Under Xi Jinping, China’s gilded age is being met with a suite of top-down policies and a further contraction of civil society, arguably inverting the dynamics seen historically in the United States. Many of the policies pursued under the auspices of the Common Prosperity campaign to date, such as the assault on the after-school tutoring business or the crackdown on tech companies, have only further impeded economic growth. In this period of declining growth the people’s expectations that the future will necessarily be brighter have started to dim. The country is therefore in a bind as it struggles to address inequality without strangling growth altogether. The social response to this predicament is the pervasive sense of involution, as people see an entrenched class system failing to reform itself as growth rates fall precipitously. People feel a sense of incredible anxiety as they strive ever harder to ensure their slice of a shrinking pie.

These trends have been massively exacerbated by Xi’s pursuit of a “zero-COVID” policy to contain the COVID-19 pandemic. The strict policy has badly destabilized the economy through snap lockdowns, constant testing, and a freeze on the geographic mobility of labor, among other measures. This was evidenced dramatically recently when video emerged showing workers fleeing a major Foxconn factory in Zhengzhou upon hearing about potential cases, traveling miles on foot along busy highways to escape the factory and the city before being locked down. Foxconn’s stock price fell nearly 3% on news of the outbreak.

The mounting frustrations of the population with the policy were well captured by a Shanghai resident during the city’s protracted lockdown in the spring of 2022, in a conversation with a local official archived by China Digital Times: “Since reform and opening started in ’79, we’ve been working for 40 years to earn a bit of wealth, but look how this month of suffering has left us,” the resident tells the official, his voice breaking with frustration. “We’re going backwards. We’ve put the car in reverse and we’re giving it gas.”

The damage that the zero-COVID policies have meted out on the Chinese economy is vast. One analyst recently even argued that the economic fallout for China could be greater than the war in Ukraine. While this estimate is probably overblown, it is clear that China is set to miss its growth target of 5.5% for 2022. If it performs at around 3.3%, as some analysts predict, then zero-COVID policies will have cost $384 billion in lost GDP this year alone. Moreover, the shattering of business confidence and the decision by many multinationals to start moving supply chains away from China will have repercussions long into the future.

Beyond the hard economic reality of these policies, they have also proven the intractability of inequality. For those with low to middle incomes, the massive spikes in food prices associated with lockdowns has cut into their already tight monthly budgets. Migrant workers have been hit the hardest. Those who work in the gig economy, such as delivery drivers, have had to choose whether to risk being infected at work — or exposed and forced into quarantine — or earning nothing whatsoever. Some drivers have ended up sleeping rough for months, unable to return to their homes because their decision to work in the city meant they could not return to their local communities. Like elsewhere in the world, knowledge workers have in comparison transitioned more easily to working from home, and despite significant struggles have managed to remain productive, while laborers and service workers have found themselves unable to continue earning as before. Rich parents have managed to keep their kids in school online, while poorer parents struggle to keep their kids up to date with schooling when they have limited internet access. According to research from Southwestern University of Finance and Economics and Ant Group Research, China’s poorest households have seen their wealth decline every quarter since the pandemic began, while the wealthiest households have actually grown richer. The pandemic has therefore underscored the sense that Chinese society is deeply unequal. It might be the same storm, but people have been reminded time and again that they weather it in different boats.

Educational Involution

Chinese society has had significant social barriers that exacerbate inequality since the launch of economic reforms in the 1970s, but one of the key determinants of success has always been educational achievement. The education system has functioned as a dramatic social filter. Students at the age of 16 take the extensive High School Entrance Exam (中考). This exam decides whether or not students are able to progress in their education and compete in the college entrance exam gaokao (高考). Those who do poorly are forced to drop out of school or to shift into vocational qualifications. The exam essentially traps a huge subsection of Chinese students into vocational education and eking out a living in service jobs. This bifurcation has rendered the education system deeply competitive and a key vector for involution.

Those lucky enough to continue their schooling face what has been called the toughest academic exam on earth. This year, the math exam for students in Zhejiang province was so hard that many students were filmed bursting into tears. It is not uncommon for students in their final year of preparation for the gaokao to study at least 12 hours a day through every year. There are reports of students who put in even more herculean efforts — in 2019, one student’s 17-hour-a-day study schedule became a viral sensation. The anthropologist Zachary Howlett has referred to the gaokao as a “fateful rite of passage.” In my own work as an ethnographic researcher, I have been struck by how often people, even those decades removed from taking the exam, would still be able to quote their scores.3 In a very real sense, the exam had altered the course of their lives.

The power of educational achievement can be seen in the case of Yongwei Jinqiao Xitang development in Zhengzhou, Henan province (hereafter "Xitang project"). The province has been wracked in recent months with waves of unrest over failed development projects, as construction companies have defaulted and failed to complete apartment buildings that they had already sold. The “Xitang project” was a development meant to be built in Zhengzhou’s high-tech development zone, near universities and a science park. The developer defaulted after a shareholder misappropriated 1.6 billion RMB, leaving the project stalled. Media reports focused intently on the education levels of the property owners. As one article noted, due to its location the building had attracted a lot of “high academic achievers” (高学历人才): there were 1,313 people with bachelor's degrees, 481 people with master's degrees, and 189 people with doctorates. Together, as one article noted, they decided to make a point of their status, posting videos online and filming their personal stories. The fact that they were such high achievers garnered significant online interest, which further pressured the developers to find the funds to continue. Their educational status conferred on them an expanded ability to assert their rights as property holders. In the midst of a nationwide mortgage crisis, it was this particular building that garnered outsized attention. Educational achievement in China represents a reputational golden ticket long after graduation.

But today educational achievement is no longer a sufficient condition for a good life. In theory, passing the gaokao is supposed to guarantee a life of improved earnings and middle-class status. Successful gaokao takers are not supposed to end up stuck on a factory line producing “made in China” products or confronting the precarity of the gig economy. Today, however, even those who have passed the gaokao — who have made safe passage into the supposed upper echelons of society — find themselves involuting. The anthropologist Susanne Bregnbaek wrote about a spate of suicides at Tsinghua, one of the top universities in China (and Xi Jinping’s alma mater) in her monograph Fragile Elites.4 Despite their success, the experience of the students Bregnbaek followed was hollow. She describes being in a train station with one of the students; he stares at the mass of people moving along the concourse before turning to her and saying, “we are on a train that is going fast, leaving the past, speeding towards the future, but nobody seems to stop and reflect on where the train is going.”5

In 2020, a student at Tsinghua became an online sensation when he was spotted cycling around campus while doing statistical modeling on his laptop. Netizens refer to people like him as “involution kings” (卷王). The fact that even the most successful students in China seem unable to rest reinforces the pervasive sense that competition has grown out of control. “Involution kings” exist because even the most elite students cannot feel certain that they will graduate into a great life.

Nobody wants to fall into the mass of unemployed people. With economic growth faltering, the threat of continued COVID lockdowns, and deep uncertainty about the future compound to create a sense in which people have to fight ever harder to succeed — teetering on their bicycles, laptops balancing across handlebars, pedaling furiously to keep up.

Burnout

But what happens to people if they stop pedaling? Involution is one metaphor among many in China that point to a growing sense of unease and anxiety about the intense competition that characterizes all aspects of society. One young woman I interviewed in Chengdu, Rui Qi, had already cycled through several jobs since graduating from college. She felt like she was close to burning out and had no idea what she wanted. When I suggested she take a break to take stock and try to map out a new path for herself, she said that would be impossible. “I can’t stop, not even for a minute,” she said, “because if you step away there are a hundred people who would fill your spot immediately.”6 This sense that people are instantly replaceable is also reinforced by phrases like cutting chives (割韭菜) — wherein people refer to themselves as an herb that, once cut, grows back (i.e. they are replaced) in a matter of days. This phenomenon was on display in February 2022, when a censor at the video streaming site Billibilli died from suspected overwork. The company wasn’t fazed, quickly fulfilling plans to hire another thousand censors in the wake of his death.

The pervasive sense of overwork in China is contributing to feelings of burnout and anxiety. Where previous generations saw white-collar work in the knowledge economy as a respite from the intensity and brutality of working conditions in factories, construction, or the service industry, the working practices at some of today’s most prominent tech companies are punishing in their own way. The phrase “996” refers to the phenomenon of working from 9am to 9pm, 6 days a week, which is traditionally standard for employees in China’s tech industry. When Alibaba’s founder, Jack Ma, was questioned about conditions for his employees, he scoffed — “I think 996 is a huge blessing…” he said, adding that employees unwilling to work long hours should look elsewhere. “Why bother joining? We don't lack those who work eight hours comfortably.”

People are thus given an impossible choice — stop competing and risk falling into the increasingly large ranks of the unemployed or continue to work harder in industries where employers know there is an easily replaceable workforce and thus do not hesitate to overwork their employees. As one user on zhihu notes, putting their Marxist studies to good use, “the root cause of social involution is that the marginal efficiency of individual social labor output per unit of time is getting lower and lower, so that the exploiting class is more inclined to hire lower-cost labor to increase their earnings, which in turn leads to lower and lower relative income of the exploited class.” This is happening at a time in which necessities in China, and around the world, are growing more expensive. Young people are driven to work incredibly hard — to the point of breaking. 996 culture was deemed illegal by authorities in 2021, but in truth, the practice is still very much alive. The harsh reality is that when someone like Rui Qi does finally burn out, her employer will be able to find a replacement in no time.

Lying Flat

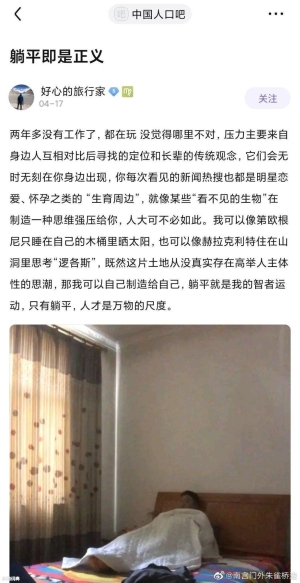

The sense that involution has reached impossible levels is captured by the phrase “lying flat” (躺平). The term is often associated with a young man named Luo Huazhong, who quit his factory job in Sichuan province and moved to rural Tibet, where he believed he could get by working odd jobs because the cost of living was so much lower. In April 2021, he wrote a post on a Baidu forum entitled “lying flat is justice” in which he argued, “I can be like Diogenes, who sleeps in his own barrel taking in the sun.” Instead of spiraling inwards, why not lie flat? As one online meme (above) points out, chives that lie flat are harder to cut.

China’s internet has always been a satirical place, even amid harsh government censorship. Terms like involution, lying flat, and more recently “let it rot” (摆烂) play well in China’s unstoppable meme culture. They also provide a pressure valve for netizens tired of conforming to government slogans promoting “positive energy” (正能量) or the need to strive towards the Chinese Dream (中国梦). These memes are an implicit critique of social reality, which allow netizens to vent their frustrations in an oblique manner that doesn’t bring them into direct confrontation with the government. To “lie flat” is by its very nature a deeply resigned form of dissent, reflecting a social reality in which protest and mass movements have been effectively crushed by Xi Jinping’s crackdowns on civil society.

Lying flat is in truth more of a rhetorical device than a social phenomenon. As of now, there is no evidence of a mass movement of young people dropping out of society altogether. But the government is clearly concerned that it could manifest into a real social movement. Lying flat has become such a cause for concern that Xi Jinping himself commented on the trend in an article for the Party’s top theory journal, Qiushi. “We must work to prevent social class solidification, smooth upward mobility channels, to create opportunities for more people to get rich, and to involve everyone in the development of the environment; in doing so we must avoid ’involution’ and ‘lying flat’.” He does not see the value in dropping out. “A happy life is achieved through struggle,” he wrote. His comments were reinforced after the 20th Party Congress when he pointedly visited the Hongqi (Red Flag) Canal, a symbolic site important to Communist Party history. There he implored the youth to “abandon the finicky lifestyle and complacent attitude.” He also reaffirmed that “China’s socialism is won by hard work, struggles and even the sacrifice of lives.”

This notion of struggle in official discourse has resonances with the Mao-era, and it was telling that Xi gave these remarks at the Red Flag canal, a large piece of industrial infrastructure started during the Great Leap Forward, which has long been touted as an example of what Chinese workers can achieve. The implication here is that China has been built through the intense industry and sacrifice of its people. For large swathes of the youth to consider dropping out therefore threatens the continued advancement of Chinese society. At a time of shaky economic growth, the government cannot afford to have young people dropout en masse. Many of Xi’s long-standing goals, such as the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese people” and the “Chinese dream of a strong nation” (中国梦 强国梦) rely on the industry of the population. Xi looks towards an international system that is ripe for China’s ascent, as the world undergoes “great changes unseen in a century.” To seize these opportunities, China cannot falter at home. As such, Xi is reaching back to Mao-era notions of struggle as an official counterpoint to these popular discourses. The fact that he feels the need to engage with them underscores the contingency of his aims, and his sense that these calls to lie flat are an implicit threat to them.

But while lying flat may not rise to the level of a social movement, the desire for a life not characterized by such harsh competition is genuinely held by many people. But there is a sad sense in which this feeling has no obvious solution. In a forthcoming book chapter, Linda Qian and I argue that involution is becoming inescapable in China today.7The irony is that many of the projects that young Chinese are turning towards to manage their sense of burnout, such as moving to rural areas or trying to facilitate their own healing through psychotherapy workshops, only end up recreating the same involuted logic they are trying to escape. In her fieldwork in rural Lishui, in Zhejiang, Dr. Qian found young urbanites who had moved to the village to set up small businesses, only to find they were competing against other young people who’d had the same idea.

Terms like “lying flat” and “involution” convey the resignation that many young Chinese feel today. Young people feel additional stress because their feelings are misunderstood by their parents and elders, who saw real material advantages result from their hard work. They saw miracles: cities rising from rice fields, the world’s largest high-speed rail network crisscrossing their nation, and the internet connecting them even further. For the generation born with these advances already largely in place, they no longer see so clearly the fruits of their labor.

There is a sense in which this is part of a global trend, as young people in the West struggle to get onto a property ladder that their parents climbed more easily, and as spiraling inflation, coupled with decades of stagnant wages, creates its own dynamics of involution. There is much in this global environment that resonates with the Chinese experience. However, in the Chinese context, many of these dynamics are directly related to government policies, and Xi’s authoritarian tendencies dictate that, instead of stepping back from intervening in society and creating greater autonomy for people to challenge these dynamics, he will further intervene via his Common Prosperity campaign. It is too early to tell what the exact consequences of this policy might be, but it seems likely to further constrict individual liberty and tighten Xi’s control of the economy — neither of which bode well as genuine potential solutions for involution.

Instead of further spiraling inwards, many young Chinese are weighing up what it might mean to live a life not constricted by the dominant norms of society. “Don’t buy property; don’t buy a car; don’t get married; don’t have children; and don’t consume” has become a new mantra of sorts. The sense that a happy life might be achieved not through struggle, but through acceptance, is spurring people to look for alternative sources of meaning. In the next paper in this ongoing series, we will look at one such avenue in the context of the rise of psychotherapy in China.

Notes

- Geertz, Clifford. 1971. Agricultural Involution: The Process of Ecological Change in Indonesia. Berkeley/Calif. U.A.: Univ. Of California Pr; Geertz was actually applying the concept as conceived by the anthropologist Alexander Goldenweiser, see McCullough, Colin. (2019). “Review of ‘Agricultural Involution: The Processes of Ecological Change in Indonesia’ by Clifford Geertz.” International Journal of Anthropology and Ethnology 3 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41257-019-0021-y.

- Alfred Chan, Xi Jinping: Political Career, Governance, and Leadership, 1953-2018 p. 182.

- Bram, Barclay 2021 We Can Only Change Ourselves: Psychological Counselling and Mental Health in China https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:a0f4faa8-fc6b-4375-aba9-44692b99b3ca…;

- Bregnebaek, Susanne (2016) Fragile Elites: the Dilemmas of China’s Top University Students Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Ibid. p.4.

- Bram, B. (2022), "Troubling Emotions in China's Psy-boom" Hau: Journal of Ethnographic Theory special section, politics of Negative Affect in China https://doi.org/10.1086/717183 p. 924.

- Qian, Linda and Bram, Barclay (forthcoming) “Involution” Keywords for Personal Development ed. Gil Hizi, Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam Press.