ASPI Climate Action Brief: India

May 6, 2022 by Kate Logan and Betty Wang

Background

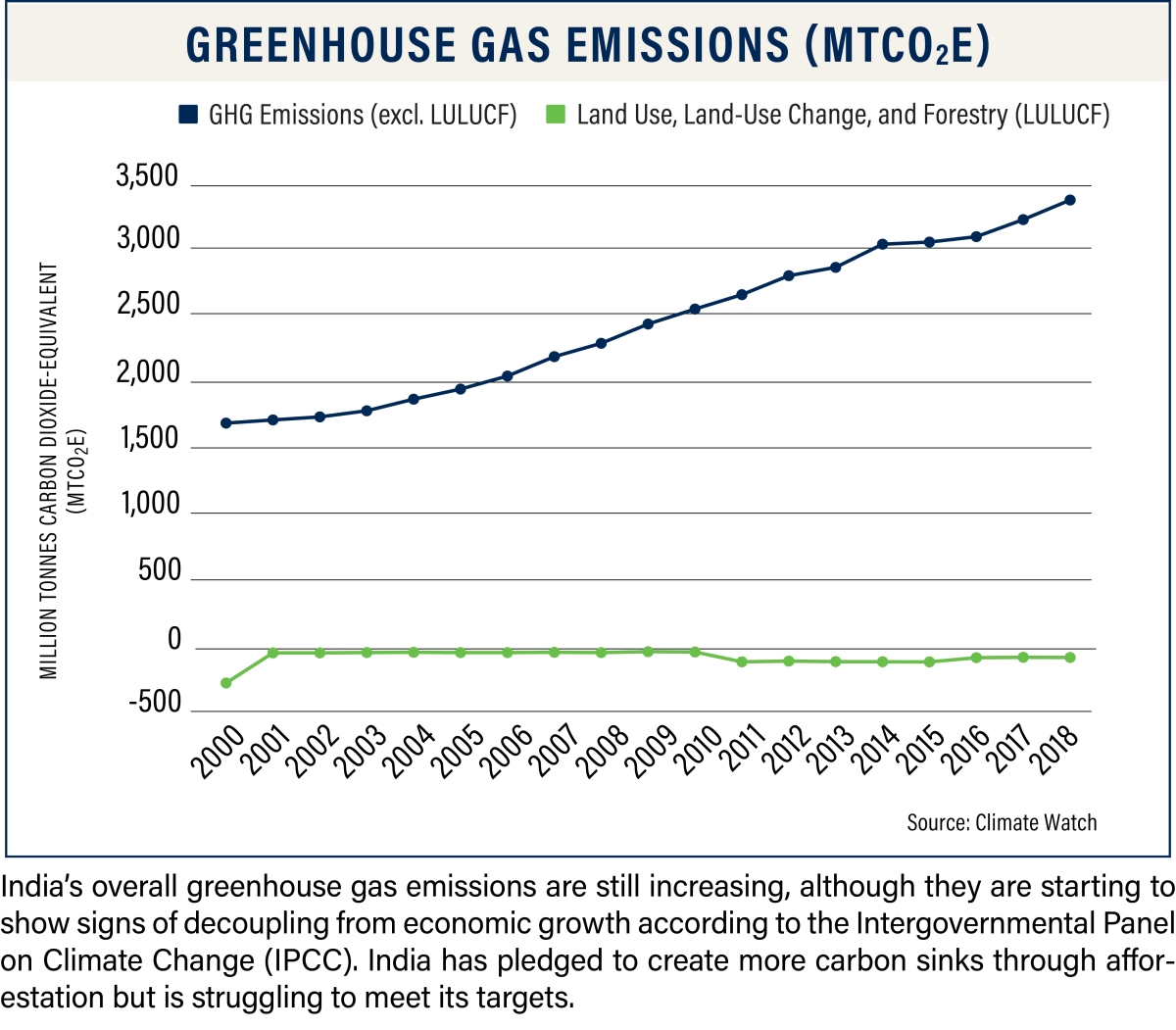

As one of the world’s fastest-growing economies in the mid-2000s, India became the third-largest annual greenhouse gas (GHG) emitter after China and the United States, although its cumulative historical emissions trail further behind. In 2008, it released its first National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC), which outlined eight national climate “missions” including those on solar, energy efficiency, water, and sustainable agriculture.

Soon after COP15 in Copenhagen in 2009, India joined the Copenhagen Accord and pledged to voluntarily cut its emissions intensity by 20%-25% from 2005 levels by 2020. The target marked a major change in India's policy on tackling climate change and showed its willingness to coordinate with the international agenda.

In 2016, India became the 62nd country to join the Paris Agreement. Representing around 4.5% of annual global emissions at the time, India was the only BASIC country among Brazil, South Africa, India, and China that did not set a carbon-peaking year. In its Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC), which it later resubmitted as its official NDC, India pledged to reduce the emissions intensity of its economy by 33%-35% compared to 2005 levels by the year 2030 which it is on track to overachieve. It also outlined a plan to increase total tree cover to create a cumulative carbon sink of 2,500-3,000 MtCO2e by 2030 — a figure roughly on par with its total emissions from a single year.

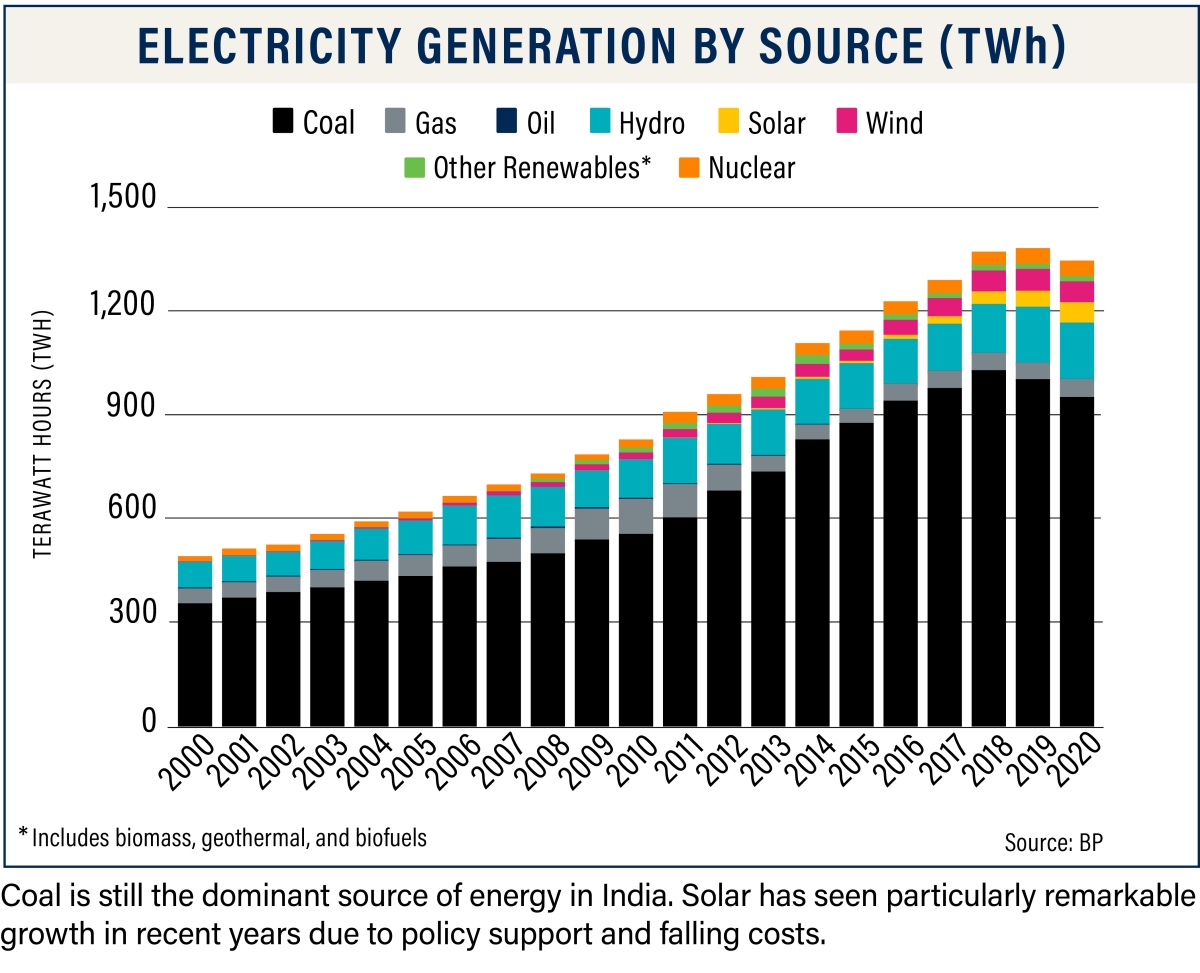

In terms of transforming its electricity mix, India aimed to have 40% of its installed electricity come from non-fossil sources by 2030. In 2019, India announced it would install 175 gigawatts (GW) of renewable energy by 2022 and 450 GW by 2030, targets more ambitious than the figures it pledged under the Paris Agreement.

Latest developments

Although signals suggested that India might update its NDC before COP26 in 2021, India did not announce any significant climate updates until Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s national statement at COP26 in Glasgow. Modi set forth five new goals or a panchamrit on climate, although India has yet to officially submit these targets to the UN’s climate change body:

- Achieving net zero emissions by 2070

- Reducing total projected carbon emissions by 1 billion tonnes between 2021 and 2030

- Increasing renewable energy to 50% of total energy requirements by 2030

- Reducing carbon intensity by 45% per unit of GDP by 2030 (from 2005 levels), up from a 33%-35% reduction target in its NDC

- Increasing non-fossil energy capacity to 500 GW by 2030

India’s 2070 net zero pledge was a particularly important moment in its climate action history, as the government had not previously indicated any decision toward setting a net zero plan.

India signed up to the UK’s Breakthrough Agenda to reduce emissions in the key sectors of power, steel, road transport, hydrogen, and agriculture by 2030. It also joined forces with the UK to spearhead the Green Grids Initiative to dramatically accelerate the global transition to clean energy by improving grid connections. Eighty countries at COP26 backed the initiative.

Meanwhile, Modi urged developed countries to make $1 trillion in climate finance available to developing countries "as soon as possible" and emphasized climate justice in technology and finance. India maintained that it would not update its NDC to reflect Modi’s pledges until more clarity is seen in climate finance. Indian officials have suggested that India alone will need $1 trillion by 2030 for renewable energy development and decarbonization.

In developing the final text of the Glasgow Climate Pact, India opposed the clause to "phaseout" unabated coal at the last minute and would only commit to "phasedown." While India received flak for publicly proposing the change, this language had already been used in the U.S.-China joint statement at COP26 and the October 2021 G20 deal. The change received support from other countries including China, Iran, and South Africa. India also did not sign key voluntary pledges on reducing methane and ending deforestation, which the country claimed did not align with its national goals.

Reading between the lines

India’s net zero by 2070 target is a very significant step forward, as India was one of the last major emitters without a target. However, India has not developed or submitted its official Long-Term Strategy (LTS) outlining its road map to net zero. Its net zero target is also at least a decade later than any other country’s target and does not align with the mid-century timeline required to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. Recent research by a major Indian think tank indicates that for India to reach net zero in 2070, it would need to reduce coal-based power generation by 99% by 2060, increase solar capacity to 1,689 gigawatts by 2050, and achieve large-scale development of hydrogen as a fuel source.

India’s new target to reduce total projected carbon emissions by 1 billion tonnes could be a significant contribution to the global carbon budget depending on the baseline that India chooses. Under a business as usual (BAU) scenario, projected CO2 emissions in 2030 could reach 4.48 gigatonnes (Gt), in which case the commitment would reduce emissions by around 22% below the predicted figure.

India’s pledge for 50% of its energy requirements to come from renewable sources is phrased ambiguously but has been signaled to refer to installed power capacity as in the pledge in its 2016 NDC. Achieving the 500 GW installed capacity target would imply that this share is more than achieved. India plans to rely in part on its renewable purchase obligation to achieve the 500 GW goal, which its renewables minister has billed as “easily achievable,” even though renewables capacity at the end of 2021 was only around 150 GW. One barrier to renewables expansion is the high debt burden of state-owned distribution companies, though this could be helped by a recent judgment allowing distribution companies to leave end-of-tenure agreements that otherwise require them to purchase inefficient coal power.

India’s carbon intensity reduction target upgrade from 33%-35% to 45% below 2005 levels by 2030 is projected to be easily achievable based on its current policies and actions. However, a reduction in carbon intensity does not necessarily mean a reduction in overall emissions.

India largely ignored land use during COP26. The country did not announce any new targets beyond its existing one to increase tree coverage, nor did it join the pledge to end deforestation. Although India has claimed that it has sufficient policies in place to reach its current goal, the data indicate it may be challenging: between 2001 and 2020, India lost 18% of its primary forest and 5% of its tree cover.

What to watch for next

Although Modi’s speech at COP26 presented a series of targets that have been widely interpreted as India’s updated NDC, India is unlikely to submit them to the UN’s climate change body until more clarity is achieved around Modi’s call for finance. Potentially delaying this is that the UN process to set a long-term finance goal will not take place until 2024. It remains to be seen whether ambitious earlier action on finance could prompt India to submit its updated NDC this year based on the Glasgow Climate Pact’s call for countries’ NDCs to be updated by COP27.

Despite its insistence on softening the Glasgow Climate Pact’s language on fossil fuels, India has been making progress on coal at the subnational and non-state levels, where states and companies that own 50% of India’s power capacity are now committed to no new coal. More subnational and non-state commitments could further India’s progress toward its climate goals while nudging the national government to adopt a more assertive stance. Reports indicate that the government may be considering halting new coal construction and retiring inefficient plants by 2023 to meet its COP26 targets.

Perhaps the biggest barrier inhibiting India’s willingness to phase out coal domestically, however, is securing a just transition for the more than 13 million Indians who are employed in coal economy sectors, the core of whom are concentrated in India’s central and eastern states. The transition could also be costly for local governments: about 40% of India’s 700+ districts have some sort of coal dependency. Comprehensive mechanisms to support workers and create alternate revenue sources for coal-dependent regions are critical for making India’s transition away from coal politically feasible.

Significant amounts of financing will be needed to close emissions reduction gaps, especially in renewable technology investment, energy storage, and coal phaseout. India is a prime candidate for a just energy transition deal in the vein of South Africa’s Just Energy Transition Partnership, with several nations purportedly exploring this possibility. Other initiatives like the Climate Investment Fund’s $2.5 billion Accelerating Coal Transition (ACT) could speed up India’s coal phaseout and just transition. India’s sheer magnitude and that of its coal industry mean that multiple avenues may be pursued in tandem.

India may also continue leveraging its own platforms for influence. Modi’s co-founding of the International Solar Alliance ahead of COP21 in Paris established his strong political commitment to renewables. Apart from the Green Grids Initiative, India also co-launched the Infrastructure for Resilient Island States (IRIS) initiative at COP26 to provide support to small island developing states on the multifaceted issues posed by infrastructure systems. The program strategically signifies India’s solidarity with some of the most climate-vulnerable nations while helping to channel in more financial support from developed countries.

In 2023, India will take up the G20 presidency and also host the Clean Energy Ministerial and Mission Innovation Ministerial. These could serve as platforms for India to further enhance its climate action reputation in the lead-up to COP28 in 2023.