The Origins of Buddhism

Buddhism, founded in the late 6th century B.C.E. by Siddhartha Gautama (the "Buddha"), is an important religion in most of the countries of Asia. Buddhism has assumed many different forms, but in each case there has been an attempt to draw from the life experiences of the Buddha, his teachings, and the "spirit" or "essence" of histeachings (called dhamma or dharma) as models for the religious life. However, not until the writing of the Buddha Charita (life of the Buddha) by Ashvaghosa in the 1st or 2nd century C.E. do we have acomprehensive account of his life. The Buddha was born (ca. 563 B.C.E.) in a place called Lumbini near the Himalayan foothills, and he began teaching around Benares (at Sarnath). His erain general was one of spiritual, intellectual, and social ferment. This was the age when the Hindu ideal of renunciation of family and socia llife by holy persons seeking Truth first became widespread, and when the Upanishads were written. Both can be seen as moves away from the centrality of the Vedic fire sacrifice.

Siddhartha Gautama was the warrior son of a king and queen. According to legend, at his birth a soothsayer predicted that he might become a renouncer (withdrawing from the temporal life). To prevent this, his father provided him with many luxuries and pleasures. But, as a young man, he once went on a series of four chariot rides where he first saw the more severe forms of human suffering: old age, illness, and death (a corpse), as well as an ascetic renouncer. The contrast between his life and this human suffering made him realize that all the pleasures on earth where in fact transitory, and could only mask human suffering. Leaving his wife—and new son ("Rahula"—fetter) he took on several teachers and tried severe renunciation in the forest until the point of near-starvation. Finally, realizing that this too was only adding more suffering, he ate food and sat down beneath a tree to meditate. By morning (or some say six months later!) he had attained Nirvana (Enlightenment), which provided both the true answers to the causes of suffering and permanent release from it.

Now the Buddha ("the Enlightened or Awakened One") began to teach others these truths out of compassion for their suffering. The most important doctrines he taught included the Four Noble Truths and the Eight-Fold Path. His first Noble Truth is that life is suffering (dukkha). Life as we normally live it is full of the pleasures and pains of the body and mind; pleasures, he said, do not represent lasting happiness. They are inevitably tied in with suffering since we suffer from wanting them, wanting them to continue, and wanting pain to go so pleasure can come. The second Noble Truth is that suffering is caused by craving—for sense pleasures and for things to be as they are not. We refuse to accept life as it is. The third Noble Truth, however, states that suffering has an end, and the fourth offers the means to that end: the Eight-Fold Path and the Middle Way. If one follows this combined path he or she will attain Nirvana, an indescribable state of all-knowing lucid awareness in which there is only peace and joy.

The Eight-Fold Path—often pictorially represented by an eight-spoked wheel (the Wheel of Dhamma) includes: Right Views (the Four Noble Truths), Right Intention, Right Speech, Right Action, Right Livelihood/Occupation, Right Endeavor, Right Mindfulness (total concentration in activity), and Right Concentration (meditation). TheEight-Fold Path is pervaded by the principle of the Middle Way, which characterizes the Buddha's life. The Middle Way represents a rejection of all extremes of thought, emotion, action, and lifestyle. Rather than either severe mortification of the body or a life of indulgence insense pleasures the Buddha advocated a moderate or "balanced" wandering life-style and the cultivation of mental and emotional equanimity through meditation and morality.

After the Buddha's death, his celibate wandering followers gradually settled down into monasteries that were provided by the married laityas merit-producing gifts. The laity were in turn taught by the monks some of the Buddha's teachings. They also engaged in such practices as visiting the Buddha's birthplace; and worshipping the tree under which he became enlightened (bodhi tree), Buddha images in temples, and the relics of his body housed in various stupas or funeral mounds. A famous king, named Ashoka, and his son helped to spread Buddhism throughout South India and into Sri Lanka (Ceylon) (3rd century B.C.E.).

Many monastic schools developed among the Buddha's followers. This is partly because his practical teachings were enigmatic on several points; for instance, he refused to give an unequivocal answer about whether humans have a soul (atta/atman) or not. Another reason for the development of different schools was that he refused to appoint asuccessor to follow him as leader of the Sangha (monastic order). He told the monks to be lamps unto themselves and make the Dhamma their guide.

About the first century C.E. a major split occurred within the Buddhist fold-that between the Mahayana and Hinayana branches. Of the Hinayana ("the Lesser Vehicle") branch of schools, only the The ravada school (founded 4th century B.C.E.) remains; it is currently found in Sri Lanka and all Southeast Asian countries. This school stresses the historical figure of Gautama Buddha, and the centrality of the monk's life-style and practice (meditation). The ravada monks hold that the Buddha taught a doctrine of anatta (no-soul) when he spoke of the impermanence of the human body/form, perception, sensations/feelings, consciousness, and volition. They believe, however, that human beings continue to be "reformed" and reborn, and to collect karma until they reach Nirvana. The The ravada school has compiled a sacred canon of early Buddhist teachings and regulations that is called the Tripitaka.

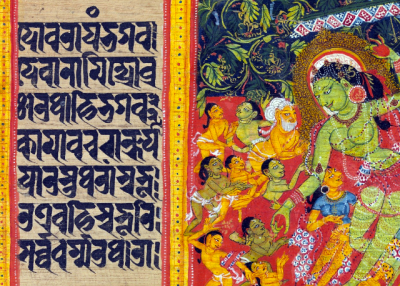

The Mahayana ("Greater Vehicle") branch of schools began about the 1st century C.E.; Mahayanists are found today especially in Korea, China, Japan, and Tibet. The three most prominent schools are Pure Land, Chanor Zen, and Tantra. Mahayana schools in general utilize texts called sutras, stressing that lay people can also be good Buddhists, and that there are other effective paths to Nirvana in addition to meditation—for instance the chanting and good works utilized in Pure Land. They believe that the Buddha and all human beings have their origin in what is variously called Buddha Nature, Buddha Mind, or Emptiness. This is not "nothing," but is the completely indescribable Source of all Existence; it is at the same time Enlightenment potential. The form of the historical Buddha was, they say, only one manifestation of Buddha Nature. Mahayana thus speaks of many past and also future Buddhas, some of whom are "god-like" and preside over Buddha-worlds or heavenly paradises. Especially important are bodhi sattvas—who are persons who have reached the point of Enlightenment, but turn back and take a vow to use their Enlightenment-compassion, -wisdom, and -power to help release others from their suffering. Mahayana canon says that finally there is no distinction between "self" and "other," nor between samsara (transmigration, rebirth) and Nirvana! Because of this the bodhi sattvais capable of taking on the suffering of others in samsara and of transferring his own merit to them.

Although Buddhism became virtually extinct in India (ca. 12th century C.E.)—perhaps because of the all-embracing nature of Hinduism, Muslim invasions, or too great a stress on the monk's way of life—as a religion it has more than proved its viability and practical spirituality in the countries of Asia to which it has been carried. The many forms and practices that have been developed within the Buddhist fold have also allowed many different types of people to satisfy their spiritual needs through this great religion.

Author: Lise F. Vail.