Introduction to Southeast Asia

History, Geography, and Livelihood

by Barbara Watson Andaya

Southeast Asia consists of eleven countries that reach from eastern India to China, and is generally divided into “mainland” and “island” zones. The mainland (Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam) is actually an extension of the Asian continent. Muslims can be found in all mainland countries, but the most significant populations are in southern Thailand and western Burma (Arakan). The Cham people of central Vietnam and Cambodia are also Muslim.

Island or maritime Southeast Asia includes Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, the Philippines, Brunei, and the new nation of East Timor (formerly part of Indonesia). Islam is the state religion in Malaysia and Brunei. Although 85 percent of Indonesia’s population of over 234,000,000 are Muslims, a larger number than any other country in the world, Islam is not the official state religion. Muslims are a minority in Singapore and the southern Philippines.

Geography, Environment, and Cultural Zones

Virtually all of Southeast Asia lies between the tropics, and so there are similarities in climate as well as plant and animal life throughout the region. Temperatures are generally warm, although it is cooler in highland areas. Many sea and jungle products are unique to the region, and were therefore much desired by international traders in early times. For example, several small islands in eastern Indonesia were once the world’s only source of cloves, nutmeg, and mace. The entire region is affected by the monsoon winds, which blow regularly from the northwest and then reverse to blow from the southeast. These wind systems bring fairly predictable rainy seasons, and before steamships were invented, these wind systems also enabled traders from outside the region to arrive and leave at regular intervals. Because of this reliable wind pattern, Southeast Asia became a meeting place for trade between India and China, the two great markets of early Asia.

There are some differences in the physical environment of mainland and island Southeast Asia. The first feature of mainland geography is the long rivers that begin in the highlands separating Southeast Asia from China and northwest India. A second feature is the extensive lowland plains separated by forested hills and mountain ranges. These fertile plains are highly suited to rice-growing ethnic groups, such as the Thais, the Burmese, and the Vietnamese, who developed settled cultures that eventually provided the basis for modern states. The highlands were occupied by tribal groups, who displayed their sense of identity through distinctive styles in clothing, jewelry, and hairstyles. A third feature of mainland Southeast Asia is the long coastline. Despite a strong agrarian base, the communities that developed in these regions were also part of the maritime trading network that linked Southeast Asia to India and to China.

The islands of maritime Southeast Asia can range from the very large (for instance, Borneo, Sumatra, Java, Luzon) to tiny pinpoints on the map (Indonesia is said to comprise 17,000 islands). Because the interior of these islands were jungle clad and frequently dissected by highlands, land travel was never easy. Southeast Asians found it easier to move by boat between different areas, and it is often said that the land divides and the sea unites. The oceans that connected coasts and neighboring islands created smaller zones where people shared similar languages and were exposed to the same religious and cultural influences. The modern borders created by colonial powers—for instance, between Malaysia and Indonesia—do not reflect logical cultural divisions.

A second feature of maritime Southeast Asia is the seas themselves. Apart from a few deep underwater trenches, the oceans are shallow, which means they are rather warm and not very saline. This is an ideal environment for fish, coral, seaweeds, and other products. Though the seas in some areas are rough, the region as a whole, except for the Philippines, is generally free of hurricanes and typhoons. However, there are many active volcanoes and the island world is very vulnerable to earthquake activity.

Lifestyle, Livelihood, and Subsistence

A distinctive feature of Southeast Asia is its cultural diversity. Of the six thousand languages spoken in the world today, an estimated thousand are found in Southeast Asia. Archeological evidence dates human habitation of Southeast Asia to around a million years ago, but migration into the region also has a long history. In early times tribal groups from southern China moved into the interior areas of the mainland via the long river systems. Linguistically, the mainland is divided into three important families, the Austro-Asiatic (like Cambodian and Vietnamese), Tai (like Thai and Lao), and the Tibeto-Burmese (including highland languages as well as Burmese). Languages belonging to these families can also be found in northeastern India and southwestern China.

Around four thousand years ago people speaking languages belonging to the Austronesian family (originating in southern China and Taiwan) began to trickle into island Southeast Asia. In the Philippines and the Malay-Indonesian archipelago this migration displaced or absorbed the original inhabitants, who may have been related to groups in Australia and New Guinea. Almost all the languages spoken in insular Southeast Asia today belong to the Austronesian family.

A remarkable feature of Southeast Asia is the different ways people have adapted to local environments. In premodern times many nomadic groups lived permanently in small boats and were known as orang laut, or sea people. The deep jungles were home to numerous small wandering groups, and interior tribes also included fierce headhunters. In some of the islands of eastern Indonesia, where there is a long dry season, the fruit of the lontar palm was a staple food; in other areas, it was sago. On the fertile plans of Java and mainland Southeast Asia sedentary communities grew irrigated rice; along the coasts, which were less suitable for agriculture because of mangrove swamps, fishing and trade were the principal occupations. Due to a number of factors—low populations, the late arrival of the world religions, a lack of urbanization, descent through both male and female lines—women in Southeast Asia are generally seen as more equal to men that in neighboring areas like China and India.

Cultural changes began to affect Southeast Asia around two thousand years ago with influences coming from two directions. Chinese expansion south of the Yangtze River eventually led to the colonization of Vietnam. Chinese control was permanently ended in 1427, but Confucian philosophy had a lasting influence when Vietnam became independent. Buddhism and Taoism also reached Vietnam via China. In the rest of mainland Southeast Asia, and in the western areas of the Malay-Indonesian archipelago, expanding trade across the Bay of Bengal meant Indian influences were more pronounced. These influences were most obvious when large sedentary populations were engaged in growing irrigated rice, like northern Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, Burma, Java, and Bali. Rulers and courts in these areas who adopted Hinduism or forms of Buddhism promoted a culture which combined imported ideas with aspects of local society.

Differences in the physical environment affected the political structures that developed in Southeast Asia. When people were nomadic or semi-nomadic, it was difficult to construct a permanent governing system with stable bureaucracies and a reliable tax base. This type of state only developed in areas where there was a settled population, like the large rice-growing plains of the mainland and Java. However, even the most powerful of these states found it difficult to extend their authority into remote highlands and islands.

The Arrival of Islam in Southeast Asia

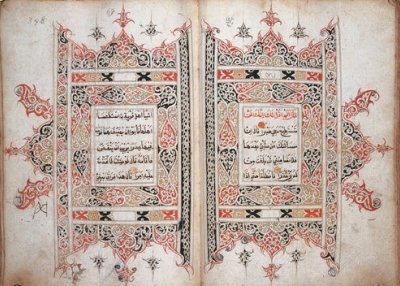

Islamic teachings began to spread in Southeast Asia from around the thirteenth century. Islam teaches the oneness of God (known to Muslims as Allah), who has revealed his message through a succession of prophets and finally through Muhammad (ca. 570-632 CE). The basic teachings of Islam are contained in the Qur’an (Koran), the revelation of Allah’s will to Muhammad, and in the hadith, reports of Muhammad’s statements or deeds. There are several specific requirements of a Muslim, which are known as the “Five Pillars”. These are: 1) the confession of faith. “I testify that there is no god but Allah and Muhammad is his Prophet”; 2) prayers five times a day, at daybreak, noon, afternoon, after sunset and early evening; 3) fasting between sunrise and sunset in the month of Ramadan, the ninth month of the lunar year; 4) pilgrimage to Mecca (in modern Saudi Arabia), or hajj, at least once in a lifetime if possible; and 5) payment of ¼º of income as alms, in addition to voluntary donations. There are no priests in Islam, but there are many learned teachers, known as ‘ulama, who interpret Islamic teachings according to the writings and commentaries of scholars in the past, and the teachings of the four schools of law practiced within the majority Sunni tradition. Sunni Muslims, who comprise about 85 percent of all Muslims, recognize the leadership of the first four Caliphs and do not attribute any special religious or political position to descendants of the Prophet’s son-in-law Ali.

After the Prophet’s death, Islam continued to expand. At the height of its power between the eighth and fifteenth centuries, a united Muslim Empire included all North Africa, Sicily, Egypt, Syria, Turkey, western Arabia, and southern Spain. From the tenth century CE Islam was subsequently brought to India by a similar moment of conquest and conversion, and its dominant political position was confirmed when the Mughal dynasty was established in the sixteenth century.

The chronology of Islam’s arrival in Southeast Asia is not known exactly. From at least the tenth century, Muslims were among the many foreigners trading in Southeast Asia, and a few individuals from Southeast Asia traveled to the Middle East for study. In the early stages of conversion, trade passing from Yemen and the Swahili coast across to the Malabar Coast and then the Bay of Bengal was also influential, as well as the growing connections with Muslims in China and India. Muslim traders from western China also settled in coastal towns on the Chinese coast, and Chinese Muslims developed important links with communities in central Vietnam, Borneo, the southern Philippines, and the Javanese coast. Muslim traders from various parts of India (e.g. Bengal, Gujarat, Malabar) came to Southeast Asia in large numbers and they, too, provided a vehicle for the spread of Islamic ideas.

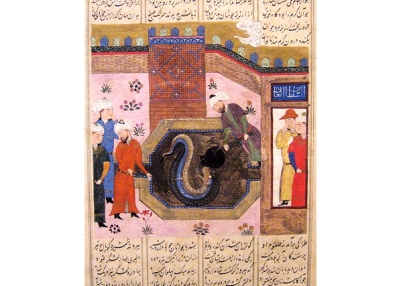

As a result of its multiple origins, the Islam that reached Southeast Asia was very varied. The normal pattern was for a ruler or chief to adopt Islam—sometimes because of a desire to attract traders, or to be associated with powerful Muslim kingdoms like Mamluk Egypt, and then Ottoman Turkey and Mughal India, or because of the attraction of Muslim teaching. Mystical Islam (Sufism), which aimed at direct contact with Allah with the help of a teacher using techniques such as meditation and trance, was very appealing.

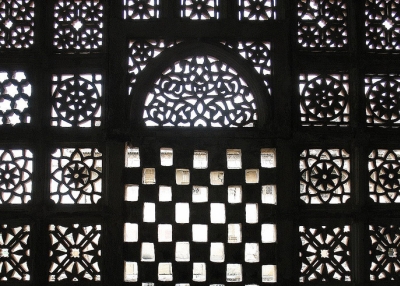

The first confirmed mention of a Muslim community came from Marco Polo, the well-known traveler, who stopped in north Sumatra in 1292. Inscriptions and graves with Muslim dates have been located in others coastal areas along the trade routes. A major development was the decision of the ruler of Melaka, on the west coast of the Malay Peninsula, to adopt Islam around 1430. Melaka was a key trading center, and the Malay language, spoken in the Malay Peninsula and east Sumatra, was used as a lingua franca in trading ports throughout the Malay-Indonesian archipelago. Malay is not a difficult language to learn, and it was already understood by many people along the trade routes that linked the island world. Muslim teachers therefore had a common language through which they could communicate new concepts through oral presentations and written texts. A modified Arabic script displaced the previous Malay script. Arabic words were incorporated into Malay, particularly in regard to spiritual beliefs, social practices, and political life.

Change over Time

Islam’s success was primarily due to a process that historians term “localization,” by which Islamic teachings were often adapted in ways that avoided avoid major conflicts with existing attitudes and customs. Local heroes often became Islamic saints, and their graves were venerated places at which to worship. Some aspects of mystical Islam resembled pre-Islamic beliefs, notably on Java. Cultural practices like cockfighting and gambling continued, and spirit propitiation remained central in the lives of most Muslims, despite Islam’s condemnation of polytheism. Women never adopted the full face veil, and the custom of taking more than one wife was limited to wealthy elites. Law codes based on Islam usually made adjustments to fit local customs.

The changes that Islam introduced were often most visible in people’s ordinary lives. Pork was forbidden to Muslims, a significant development in areas like eastern Indonesia and the southern Philippines where it had long been a ritual food. A Muslim could often be recognized by a different dress style, like chest covering for women. Male circumcision became an important rite of passage. Muslims in urban centers acquired more access to education, and Qur’anic schools became a significant focus of religious identity.

Reforming tendencies gained strength in the early nineteenth century when a group known as the Wahhabis captured Mecca. The Wahhabis demanded a stricter observance of Islamic law. Although their appeal was limited in Southeast Asia, some people were attracted to Wahhabi styles of teaching. There was a growing feeling that greater observance of Islamic doctrine might help Muslims resist the growing power of Europeans. Muslim leaders were often prominent in anti-colonial movements, especially in Indonesia. However, the influence of modernist Islamic thinking that developed in Egypt meant educated Muslims in Southeast Asia also began to think about reforming Islam as a way of answering the Western challenge. These reform-minded Muslims were often impatient with rural communities or “traditionalists” who maintained older pre-Islamic customs. Europeans eventually colonized all Southeast Asia except for Thailand. Malaya, Burma, Singapore, and western Borneo were under the British; the Dutch claimed the Indonesian archipelago; Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam were French colonies; East Timor belonged to Portugal; and the Spanish, and later the Americans, controlled the Philippines.

After these countries gained their independence following World War II, the major question for politically active Muslims has concerned the relationship between Islam and the state. In countries where Muslims are in a minority (like Thailand and the Philippines) this relationship is still causing tension. In Malaysia, Muslims are only around 55 percent of the population and there must be significant adjustments with the largest non-Muslim group, the Chinese. In Indonesia, Muslims are engaged in a continuing debate about different ways of observing the faith, and hether Islam should assume a greater role in government.

Discover Asia

Thank You for Reading!

If you’d like to support creating more resources like this please consider donating or becoming a member.