Improvisation, Insight, and Inquiry

By Chris Livaccari

January 2010

In a recent article, I made reference to Daniel Pink’s set of the “Six Senses” needed for success in what he dubs the new “Conceptual Age,” and I also introduced my own three concepts of “Improvisation, Inquiry, and Insight,” and their relevance to the world language classroom. While all of these ideas address the current educational challenges we face, they are not completely without precedent—indeed, I am constantly struck by the work of Maria Montessori, who pioneered an approach to education in the early part of the twentieth century that was student-centered, discovery-based, and was predicated on the notion of students as self-directed, thinking beings rather than empty vessels waiting to be filled. It’s amazing how, more than 100 years after Dr. Montessori established the first Montessori school, our school system in many ways still resembles a nineteenth-century factory.

In a 2003 article in Harpers magazine, John Taylor Gatto, a career educator in New York City, contributed an article entitled “Against School,” in which he offers the following imperative to parents and educators:

School trains children to be employees and consumers; teach your own to be leaders and adventurers. School trains children to obey reflexively; teach your own to think critically and independently. Well-schooled kids have a low threshold for boredom; help your own to develop an inner life so that they'll never be bored. Urge them to take on the serious material, the grown-up material, in history, literature, philosophy, music, art, economics, theology—all the stuff schoolteachers know well enough to avoid. Challenge your kids with plenty of solitude so that they can learn to enjoy their own company, to conduct inner dialogues. Well-schooled people are conditioned to dread being alone, and they seek constant companionship through the TV, the computer, the cell phone, and through shallow friendships quickly acquired and quickly abandoned. Your children should have a more meaningful life, and they can.

While Gatto’s perspective may seem extreme, he is obviously reacting to a lifetime of teaching in America’s largest urban school system, the very one in which I worked for most of the past five years. I can envision high schools becoming more like offices one day, in which each student has his or her own cubicle with workspace, computer, etc., and has to manage his or her own appointments with teachers, class schedule, and extracurricular activities. But we’ll never get to that stage of the game unless we start committing to a pedagogy that prepares students to love learning and exploration, and to really own and embrace that process—which brings us back to “improvisation, inquiry, and insight.”

Improvisation

“Improvisation” for me is the idea that learning is a dynamic and constantly evolving process that should involve surprises and unexpected challenges. At the beginning levels of language learning, I often see teachers asking their students to memorize prepared dialogues. While there is a place for this kind of exercise, I always encourage teachers to use these written conversations as jumping off points for participation in role plays that involve unrehearsed scenarios, interaction, and often humor. When I ask students to participate in role plays, I always introduce myself at the end as an unexpected character and I ask questions that are within the student’s ability, but which he or she has not necessarily heard before.

For example, every year I ask my students to create a restaurant concept complete with a name, sign, and menu, and have them act as customers and wait staff to practice the language they’ll need to order in a restaurant or have a meal with friends. When the students engage in their role plays around the restaurants they have created, I will always turn up as a difficult, confused, or completely crazy customer, who forces the students out of their comfort zone, and (I hope) beyond some of their anxieties about using language and into the realm of discovering the strength of their growing linguistic skills. The key thing to remember is that students will always be using language in a dynamic context. I’m sure many of us remember the first time we landed in a foreign country and found that we were completely unprepared for dealing with the rapid-fire language that native speakers throw our way.

Inquiry

Improvisation is the first stage in bringing students to the full realization of their language learning skills. The second is “inquiry,” and this is where I think the link between academic rigor and student engagement is most clearly visible. By inquiry, I really mean what I like to call “student as linguist.” In many classrooms, I continue to see teachers lecturing on grammar points and then asking the students to practice these. While there is certainly a place for this approach in the contemporary classroom, we can be using a more discovery-based approach with authentic language earlier on. In math and science classes, we often ask students to think like mathematicians or scientists, so it makes perfect sense to ask them to think like linguists in the context of a world language class. While it is often more efficient to directly teach students grammatical points and sentence patterns, it is also possible to give students a rich array of authentic language and then ask them to figure out how it works, how it is structured, and what it means.

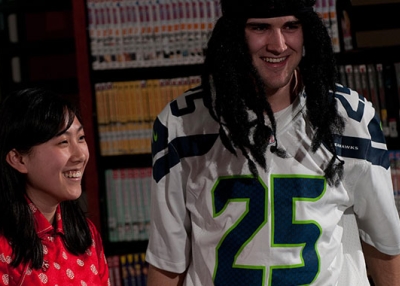

For my first-year Japanese students, one of my favorite activities was the teaching of command forms, which I introduced through a video I made with my wife – with whom I studied Japanese in Tokyo – in which she follows me around the house in an overbearing way, telling me not to “drink sake” but to “drink milk” instead; not to “read comic books” but to “read textbooks” instead; not to “listen to rock music” but to “listen to classical music” instead; not to “play” but to “clean.” The students generally laugh hysterically at seeing me so abused and put upon and I usually start the whole presentation by telling the students about my terrible marital troubles and how much I need their help!

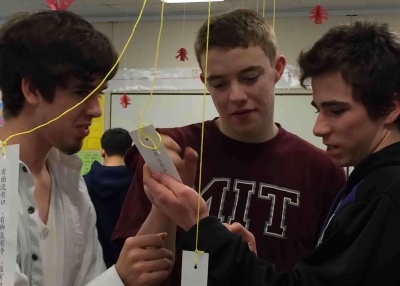

After watching the video, I ask the students not only to tell me what form of the verb my wife was using, but also to tell me the structure and analyze the ways in which the form is made as well. By doing so, students develop their listening skills and have to use context clues to more clearly understand the structure of language. The students work in groups to analyze and come up with all the appropriate forms for positive and negative commands in Japanese, and then move on to create original skits in which they have a difficult boyfriend, parent, or roommate, not unlike my “difficult wife.” In this way, students enter the language through inquiry, make it their own by having their own analyses and conclusions validated, and then move on to practicing the language in a simulated—though ideally somewhat authentic—setting.

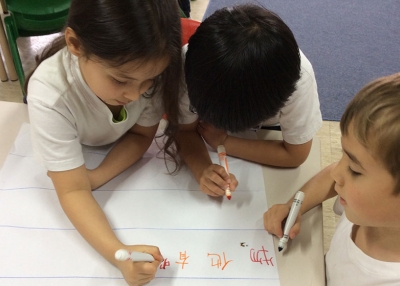

In Chinese, this kind of learning works wonderfully when introducing Chinese characters, for example. When I learned Chinese characters as a university student, I was given a list of 200+ radicals and asked to memorize them. But rather than simply telling students about radicals, I like to arrive to the first week of class with a pile of hundreds and hundreds of index cards with Chinese characters on them. The students first need to sort and organize the cards by identifying similar radicals, and then to look at the characters’ English meaning and make a guess as to what the radical indicates. For example, after matching the words for “speaking,” “talk,” “language,” etc., by identifying similar graphic components in the characters, the students make the inference that they have discovered a radical with the meaning of “speech” or “language.” In this way, I give the students the authentic language and allow them to discover what it means. In learning to articulate this new knowledge, they develop an even deeper intuitive understanding of the language.

Another good technique in the same vein is to collect video clips of movies or TV dramas in which the characters use a certain type of language—time words, greetings, color words, etc.—and to have the students analyze the material and come up with their own chart of these words, expressions, or grammatical structures. In my Chinese and Japanese classes, I have had great fun using video clips of TV drama scenes about dating, a popular subject with teenagers. It’s amazing how the least engaged boys in the class suddenly start paying strict attention once they believe they’re going to be exposed to language that will allow them to meet girls!

And through this process, you wind up showing these students that they are smarter than they think and that they have the intelligence to decipher, interpret, and analyze new language on their own, without the constant intervention of the teacher. It’s a subtle way of motivating them with something seemingly frivolous, but it actually translates into a kind of intrinsic motivation that boosts the student’s self-image and self-esteem. This is why understanding your students is so important, and asking them to understand themselves better is the core component of the third part of my conceptual framework, which I call “insight.”

Insight

“Insight” involves asking students to be reflective about their learning and to engage in a constant process of self-discovery. In being reflective, I really mean that students learn to make associations between the target language and their native language, and between academic course content and their daily lives and experiences. One example of asking students to think in this way is simply to ask students to compare the grammar, phonology, or sentence structure of the target language with that of English. This seems like a simple task, but it can be very effective in helping the students understand how language works—not just English, not just Chinese, but language in general.

The other important aspect of “insight” is creating opportunities for students to understand and think about their own challenges, strengths and weaknesses as learners. This is where self-assessment can be a powerful tool, and helping students become more accurate in their assessment of their own performance and skills is ultimately the most significant gift you can offer them.

In Daniel Pink’s latest book Drive, he offers the following: “The science shows that the secret to high performance isn’t our biological drive or our reward-and-punishment drives, but our third drive – our deep-seated desired to direct our own lives, to extend and expand our abilities, and to live a life of purpose.” While children will always need guidance and direction, allowing them a taste of autonomy in the educational process will give them the skills to become lifelong learners, successful workers, and compassionate citizens. This starts by letting them learn intuitively by “improvisation,” through discovery by “inquiry,” and through a deeper understanding of themselves as learners and the larger context of the language through “insight."

Discussion

How have you used improvisation in your teaching? How have you encouraged insight and inquiry?