World Language Teachers Find Familiar Ground with the Common Core

Heather Clydesdale on how world language teachers can align their curriculum with the Common Core State Standards. This article covers a breakout session on that very topic from the 2015 National Chinese Language Conference with speakers Janice Dowd, Lucy Chu Lee, and Carol Chen-Lin.

"I think they really stole from us," smiles Dr. Janice Dowd, talking about the similarities between the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) and longtime pedagogical approaches of world language teachers. Dowd, who serves as director of Glastonbury STARTALK for Chinese teachers in Connecticut, urges language teachers not to avoid the national discussion about the CCSS, and also offers encouraging news: language teachers are already versed in the CCSS emphasis on multiple perspectives, communication, and collaboration. Speaking of aligning their curriculum with the CCSS, Dowd tells world language teachers, "You can do it. You are already doing it."

As a case in point, Dowd notes that the English language arts (ELA) K–12 standards emphasize reading, writing, speaking and listening, and language—all of which are the central focus of world language teachers. The aim of these standards is to prepare students for settings where people from "divergent cultures and who represent diverse experiences and perspectives must learn and work together." Dowd says, and then sighs, “Finally, English language arts people are understanding what language is all about."

In fact, there are obvious correlations between the ELA standards and the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Language's (ACTFL) "Five Cs" for foreign language learning: communication, cultures, comparisons, connections, and communities. These also correlate to the "Four Cs" developed by the Partnership for 21st Century Learning: communication, collaboration, critical thinking, and creativity. The Common Core ELA standards encourage teachers to use a range of reading materials representing different levels of complexity, and ask students to integrate information, evaluate a speaker’s point of view, and present knowledge and ideas. "This is at the heart of language learning," observes Dowd.

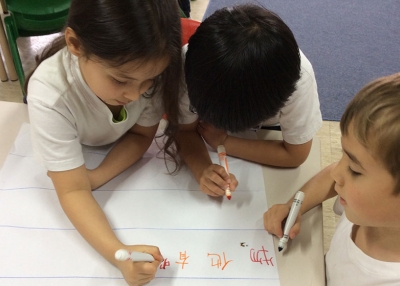

Yet, even as they find that they are familiar with the CCSS, world language teachers can still be more intentional in integrating the standards into their teaching. Dr. Carol Chen-Lin, Chinese teacher and director of summer and academic term programs at Choate Rosemary Hall, demonstrates how with her unit titled "Global Awareness."

In a lesson on China’s economy, she asks students to choose a top company operating in China and find out its secrets to success. Students conduct research on the Internet and interpret and analyze the informational texts they locate. One group of students may decide to focus on Ikea, scouring Internet reviews (an excellent source of authentic language and contemporary usage) to find out why Chinese consumers like the company and then make a video about designing a bedroom. Another group may choose Starbucks, exploring how the company created new flavors such as green tea, mango, and red bean to appeal to Chinese customers; and how they adjusted product pricing to accommodate the cultural penchant for lingering at tables longer than American customers.

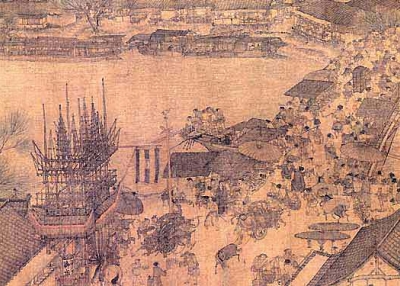

After students share their findings through video commercials, dialogue exchanges, and multimedia presentations, Chen-Lin introduces them to the Silk Roads, the network of trade routes that connected China to central, west, and south Asia and to Europe, and explores how cultural interchange and global economic exchanges have been taking place for more than two thousand years. As they analyze how China’s global economy affects their lives, and how they can work within that structure, "they use a lot of higher order thinking skills," explains Chen-Lin. Such skills are exactly what the CCSS seek to develop.

The CCSS, which have been adopted by 42 states plus the District of Columbia, were created in a joint effort by the National Governors Association (NGA) and the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO) in response to concerns in the American public and business community about the readiness of college students and the workforce to perform in the globally connected 21st century. The standards stipulate what students should know and be able to do at the end of each grade in mathematics and English language arts.

Lucy C. Lee, a veteran teacher of Livingston High School in New Jersey, explains that early on in the process, the NGA and CCSSO talked to business and corporate leaders who felt students were not equipped with the skills needed for a global economy. Lee says the CCSS "reflect what the corporations and business world want. They get students ready for the 21st century and for the world."

Specifically, the CCSS are designed to be applied consistently across the United States and evaluated using common and comprehensive assessments that will replace inconsistent and outdated state testing systems. Their core focus is developing higher-order thinking.

"Just speaking in a foreign language is higher order thinking," Dowd points out. At the same time she also urges world language teachers to see the CCSS as an opportunity to reach higher, asking, "Collaboration, creativity, critical thinking: what are the things that you do in your classroom where you could add more?"