Academic Rigor and Student Engagement

A Perfect Match

By Chris Livaccari

November 2009

To Please and Instruct

As a teacher, I’ve often worried about some of my own classroom practices—like the time I asked my students to create their own Chinese language soap opera, and they wound up creating sordid tales of adultery, murder, cross-dressing, and just pure silliness. Was it appropriate to let a fifteen-year-old boy play the role of a pregnant teenage girl, or a sixteen-year-old girl play a heartless boy who bounced from girlfriend to girlfriend? I soon feared that parents would complain when they learned what was going on in their child’s Chinese class (though no one ever did complain). On reflection, I am amazed by the breadth of language the students retained, and how they came to love learning Chinese. That boy who played the teenage mother—and who received our classroom's mock Academy Award for “Best Dramatic Performance” by almost unanimous vote—is now a college student who endeavors to become a Chinese language teacher himself. Another student still remembers every line of the Blink 182 song she translated into Chinese and can sing it on cue!

I’ve often heard debates between teachers on the challenge of maintaining a rigorous curriculum while still engaging and motivating students. As I’ve traveled around the country visiting Chinese language classrooms, I’ve seen everything from the absolutely fantastic to the utterly abysmal, but the one thing I don’t often see is an appropriate balance of academic rigor and student engagement. Rather, I find that teachers fear what might be seen as “turning the asylum over to the inmates” and letting students discover the joys of learning for themselves.

In a video interview posted on YouTube, John Rassias uses the dictum “to please and instruct,” and I couldn’t agree more with his ideas on what it takes to be an effective teacher. While I’m not a slavish proponent of the “Rassias Method”—or any other “method,” for that matter—I do find him a kindred spirit in promoting the idea that language learning needs to be fun and surprising in order to be effective. Case in point: Rassias describes a project he devised for his French students at Dartmouth, where he literally stranded them in the middle of a remote rural village in France, and let them find their own way back to Paris using their French language skills and cultural knowledge!

Engaging Students, Motivating Teachers

While I’m not yet considering dropping a bunch of teenagers into Gansu and hoping they can find their way to Shanghai, I do think the ideas of surprising students and making learning a dynamic process are extremely important. In trying to strike the right balance between student engagement and academic rigor, I’ve been reminded that this is as much about teacher engagement as it is about student engagement. Part of the reason I encouraged off-the-wall, creative approaches from my students is that teaching color words, shopping terms, or time expressions can get pretty dull the fifth, sixth, or tenth time you teach them. By allowing my students to own the language, to play with it, to discover and create it, I made the classroom not only a place they wanted to be, but also one where I wanted to be as well. It was a place where I could discover new things each day, just as they could.

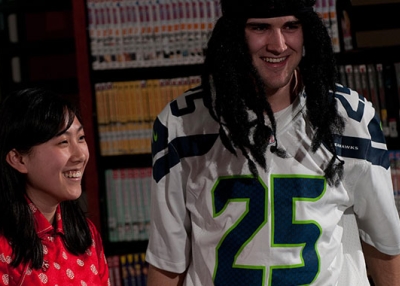

Some would say that this kind of engagement can only come at the expense of academic rigor, but I can’t agree. In fact, I have often been surprised to encounter third- and fourth-year Chinese students—in high performing schools with off-the-charts test scores—who can barely introduce themselves or answer a simple question in Chinese. In thinking about the rigor–engagement relationship, I have come to understand that they are truly two sides of the same coin, particularly in the early stages of language learning. Learning language at the beginning level is best achieved through play, even for adults. In running workshops, I see clearly how much adults enjoy language learning through movement, chanting, music, drama, and comedy—the kinds of activities that many see as more appropriate for the elementary school classroom.

In addition to embracing the language learning experience, our students need a different set of skills in order to succeed in the world. This skill set necessitates a different approach to instruction, and in the next section I have broken this down into three concepts: improvisation, inquiry, and insight.

A Whole New Mind

In his book, A Whole New Mind, Daniel Pink explores the new kinds of skills people need to be successful in the twenty-first century. He asserts that the Industrial and Information Ages are over, and that we are now moving into what he calls a new Conceptual Age. In Pink’s definition, the Conceptual Age is one in which information is ubiquitous and the most successful people are those that can analyze and synthesize many different kinds of information, and create and design new products and services. I think Pink’s book is a corrective to the kinds of practices that currently characterize the American education system.

In an interview he conducted with Tom Friedman in a recent issue of School Administrator (February 2008 Number 2, Vol. 65), Pink argues that people are naturally curious but that our education system “suffocates” that curiosity. Friedman agrees, and concludes: “And that’s why the Steve Jobses and the Bill Gateses drop out. What does it tell you when two of our greatest innovators are both college dropouts?” He cites a “favorite story about [Apple CEO] Steve Jobs' speech at Stanford's graduation. He says, ‘You know, I dropped out of Reed College and had nothing to do so I took a course in calligraphy. And it all went into the Mac keyboard!’ That was not an algorithm. That was a question of style and it helped define Apple's niche. Now, that's not to put down algorithms. Apple needed those algorithms to enable it all to happen. It's just you've got to have both. It's about integrating the two.” And we can’t teach students to communicate effectively in a new language purely by using algorithms, either.

Pink argues for a set of “Six Senses” that are crucial to our Conceptual Age: Design, Story, Symphony, Empathy, Play, and Meaning. Here’s how Pink defines each of these, and how I interpret them in the context of our Chinese language classrooms:

Not just function but also DESIGN.

“It’s no longer sufficient to create a product, service, an experience, or a lifestyle that’s merely functional. Today it’s economically crucial and personally rewarding to create something that is also beautiful, whimsical, or emotionally engaging.” (Pink, 65-66)

In the Chinese language classroom, DESIGN means creating comprehensive products using a wide range of media and technologies, rather than just completing assignments.

Not just argument but also STORY.

“When our lives are brimming with information and data, it’s not enough to marshal an effective argument. Someone somewhere will inevitably track down a counterpoint to rebut your point. The essence of persuasion, communication, and self-understanding has become the ability to fashion a compelling narrative.” (Pink, 66)

In the Chinese language classroom, STORY means connecting instructional content to students’ lives and helping students understand how to make meaning through storytelling.

Not just focus but also SYMPHONY.

“Much of the Industrial and Information Ages required focus and specialization. But as white-collar work gets routed to Asia and reduced to software, there’s a new premium on the opposite aptitude: putting the pieces together, or what I call Symphony. What’s in greatest demand today isn’t analysis but synthesis – seeing the big picture, crossing boundaries, and being able to combine disparate pieces into an arresting new whole.” (Pink, 66)

In the Chinese language classroom, SYMPHONY means seeing, seeking, and understanding connections among content areas and completing interdisciplinary projects.

Not just logic but also EMPATHY.

“The capacity for logical thought is one of the things that makes us human. But in a world of ubiquitous information and advanced analytic tools, logic alone won’t do. What will distinguish those who thrive will be their ability to understand what makes their fellow woman or man tick, to forge relationships, and to care for others.” (Pink, 67)

In the Chinese language classroom, EMPATHY means creating a community that supports students in their emotional development and helps them become responsible, independent citizens.

Not just seriousness but also PLAY.

“Ample evidence points to the enormous health and professional benefits of laughter, lightheartedness, games, and humor. There is a time to be serious of course. But too much sobriety can be bad for your career and worse for your general well-being. In the Conceptual Age, in work and in life, we all need to play.” (Pink, 67)

In the Chinese language classroom, PLAY means understanding that learning is fun and that imagination is a key element of intellectual life.

Not just accumulation but also MEANING.

“We live in a world of breathtaking material plenty. That has freed hundreds of millions of people from day-to-day struggles and liberated us to pursue more significant desires; purpose, transcendence, and spiritual fulfillment.” (Pink, 67)

In the Chinese language classroom, MEANING means using rich, deep questioning techniques in the classroom, asking teachers and students to continually reflect on their practices, and challenging them to consider issues from multiple perspectives.

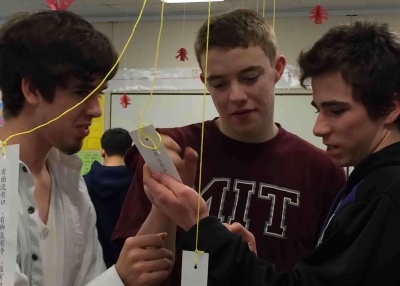

In order to make this discussion more explicitly applicable to the world language classroom, I use the three concepts of improvisation, inquiry, and insight. These refer specifically to instructional strategies that can create the bridge between academic rigor and student engagement, and create the habits of mind necessary for students to succeed in the Conceptual Age.

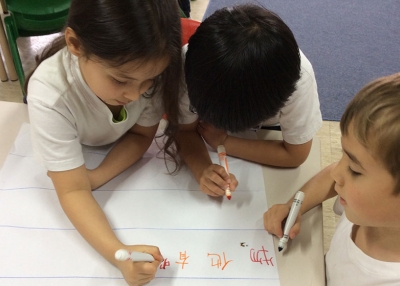

Improvisation is the teacher’s ability to create learning experiences that not only engage and instruct, but also change, develop, and evolve. So rather than memorizing a dialogue, for example, students are placed in interactive role-plays or simulations that involve unpredictable or unexpected outcomes or challenges, and force them to adapt and improvise.

Inquiry is the teacher’s ability to construct activities that fall into the category of what I call “Student as Linguist.” After all, math teachers ask their students to think like mathematicians and history teachers ask them to think like historians. It’s only appropriate that we ask our students to think like linguists. That is, rather than providing language points for students to learn, we allow them to explore authentic language, and to discover those patterns and rules for themselves. Show them a set of video clips from a TV drama in which time expressions are used, for example, and then ask the students to use context clues to figure out how to say the words for “today,” “tomorrow,” “yesterday,” etc. and to figure out where in a Chinese sentence they should be placed.

Insight is the teacher’s ability to help students make connections between their language learning experiences and their other life and academic experiences. This could mean, for example, allowing students to compare the structures of English and Chinese and the specific challenges they may face in distinguishing tones, learning characters, or using particles correctly.