Bringing 'American Food' to the Streets of China

After living in China in the late 1990s and repeatedly returning to visit, American Howie Southworth felt his stories and photos still weren’t quite getting across “the essence” of China to friends and family back home. He also noticed that his Chinese friends were often curious about what he ate in the U.S. So to kill two birds with one stone, he started the web series Sauced in Translation in order to give both sides a window into the other through the most basic tool of cross-cultural communication: food.

For the series, he and his friend Greg Matza travel to a different Chinese city for each episode and try the local cuisine. But the twist comes when Southworth, a classically trained cook, attempts to make an American-style meal for a Chinese crowd using only local ingredients. This has led him to taking over restaurant kitchens, a college cafeteria, and even a street-side food stand.

At Asia Society’s 2016 National Chinese Language Conference from April 28-30, Southworth will join a panel to discuss bridging cultures through food. Ahead of the conference, he spoke with Asia Blog about what “American food” is to China and how locals respond when he enters their kitchens and alters their perceptions.

What does “American food” mean to most Chinese?

Most Chinese don’t have a clear definition of American food, per se. Throughout China you’ll see McDonald’s, Pizza Hut, and KFC, and we assumed people recognized those as American brands. In some cases, particularly among the educated and the young, that may be true, but we've asked hundreds of people on the street if they've eaten American food and they most often say no. Then we mention the fast food chains and they occasionally reconsider their answer.

There's a fundamental difference in the way that Americans view international cuisines compared to Chinese. Americans live in a country built on immigration, so we tend to categorize by region, country, if not specialty when it comes to dining. “Let's go grab some sushi,” or “hey, you up for Ethiopian tonight?” Chinese, on the other hand, have a very long history of isolationism, and they're much more likely to see food as binary. It’s either Chinese — and that can be very rich and varied — or "other." So, the fast food joints fall into what I think is the "other" category.

For those who do make the connection to these ubiquitous fast food chains, what kind of impression does that tend to leave about “American food?”

Sure, the hamburger at McDonald’s is the hamburger at McDonald’s and that is American, but overall it’s not an exceedingly accurate impression. Despite being American brands with familiar logos, even Americans may not recognize some the food that comes out of these kitchens as American. Some McDonald’s have spring rolls, KFC serves warm soy milk during breakfast, and Pizza Hut serves noodle soup.

In fact, the Chinese Pizza Hut menu is encyclopedic and includes some real gems. Recently they added durian pizza to their menu. For those not familiar, durian is a spiky fruit with a strange meaty texture and rather putrid odor. It’s horrible. Granted, durian has its place and it's very popular in Southeast Asia. Whether Chinese people believe this to be American, I can't speak to. I sincerely hope not. When durian becomes a topping, pizza ceases to be pizza.

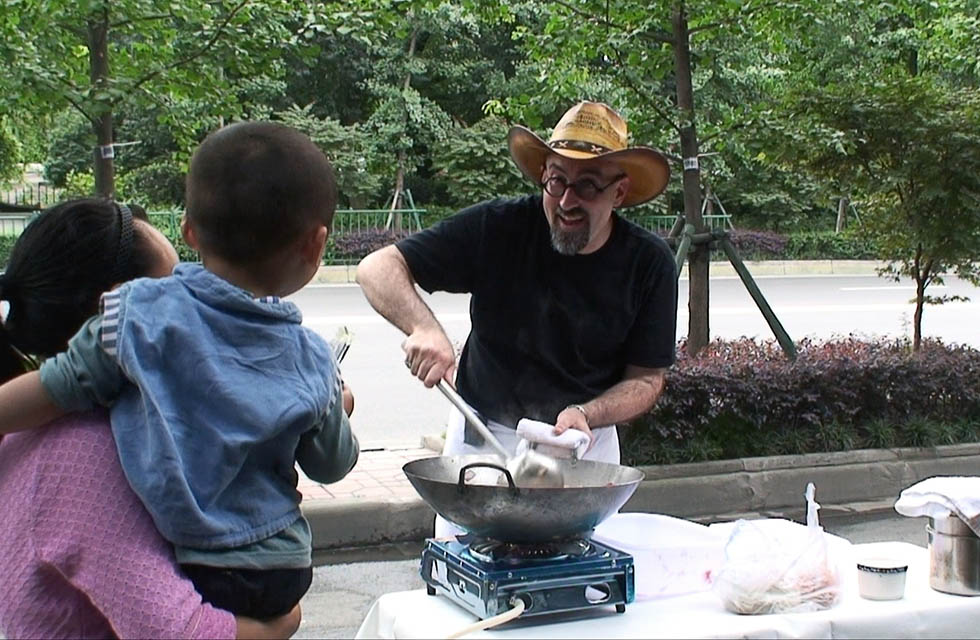

Howie Southworth cooks chili on the street in "Sauced in Translation" episode 1 in Chengdu, Sichuan, China. (Howie Southworth)

On Sauced in Translation, what have been some of the dishes you’ve made for Chinese locals that went over especially well?

The biggest hit was chowder in a bread bowl that I cooked in Harbin in far Northeastern China. That was amazing — local buttery river fish, fresh cream from a countryside dairy, these huge sourdough loaves hot out of a bakery that was built by Russians a hundred years ago. Sourdough in China? Mind=Blown. The reason the chowder was so popular was that it was essentially a reformatted version of things locals already enjoy. One of the main missions of Sauced in Translation is to do exactly that: Serve what locals love, surprisingly reshaped into an American dish.

A very close second was the spicy chili in Chengdu — that was a triple, if not a home run. It almost goes without saying. Beef, soybeans, tomatoes, chilies, and beer. Nobody goes wrong with that roster in Sichuan province. How these ingredients came together may have been unfamiliar, but the flavors and what they evoked very much matched the local palate. Indeed, one woman came to a dead stop on her bike in front of where I was cooking and exclaimed, “That Chinese food smells great!”

It may well be a cool adventure for the locals to eat the food that I cook, but it's also a remarkable experience for Greg and me. We’re not out to prove anything, necessarily, but we are, almost by accident, discovering that there are a lot more similarities between American and Chinese cuisines than most people appreciate. I think the series highlights this well.

Any culinary disasters you’ve thrust upon locals?

Any missteps on Sauced usually involve a comedy of errors. My failures are less about how a dish is received and more about being faced with an unfamiliar location, strange ingredients, or I’ll admit, chemistry. In episode six of Sauced, I cooked in a college cafeteria on Hainan Island. Eggplant parmesan was an inspired idea, but trying to make mozzarella out of ultra-pasteurized Chinese milk turned out to be a disaster. I won’t give away the ending, but let’s just say that I ended up inventing a new American dish.

I’ve also come close to disasters, but got lucky in the end. In episode 8 of the series, which is now in post-production, I make veggie burgers. I wed myself to the concept after discovering the amazing wild mushrooms in deep southwestern Yunnan province, but buns became a problem. I must have eaten hundreds of breads off camera before I found something eerily similar to slider buns, very atypical for China. That was a close one.

What’s the most unique Chinese food you’ve encountered in your travels?

Where does one begin? We had this amazing meal, also in Yunnan province. We asked this well-renowned chef for a survey of local cuisine, and he did not disappoint. This guy was the mad genius of foraging, but his prize was moss. He brought to the table a small covered bowl of soup for each of us. When we removed the lid, what appeared was a huge lump of tree moss floating in chicken broth. But, what we guessed was a mass of moss was actually a moss covered meatball. I may actually be the first American to have used that exact phrase. It was delicious, extremely local, and a revelation. Luckily, the cameras were rolling, so we caught that dish on film to share with our viewers.

Moss-covered meatballs in Qilin, Yunnan, China. (Howie Southworth)

What are some of the big regional differences in eating customs around China that you’ve noticed?

The enormity of China is definitely underappreciated. We try to highlight the uniqueness of each location we shoot on Sauced. Every region has had thousands of years to develop cuisine based on the local climate, produce, and customs. When you sit down for a meal, this becomes very clear. In the northeast, it's very cold and very dry, so you’ll see a lot of hearty stews made with ingredients like cabbage that will keep over the long winter. The southwest, on the other hand, is steamy, mountainous and verdant. There, you are likely to see simple, amazingly fresh, quickly fried veggies. The water towns near the east coast are all about fish and sea food. The areas around Shanghai, Zhejiang, and Jiangsu are filled with these little joints that specialize in crayfish, shrimp, or oysters. If you’ve never tried hairy crab, you’re missing out.

For eating, Beijing is also incredible. Here, one is able to experience all of the above within a day. It is a melting pot, like New York. Without leaving the city limits one is able to eat the entirety of China: the finest Cantonese dim sum in the morning, a noon time street snack from Shandong province, and perhaps a knock-your-socks-off Sichuan dinner to cap it all off. I’m making myself hungry.

Increasingly, many Chinese cities are offering what Beijing has for years. Regional restaurants are becoming more and more popular. That’s not to say that each city doesn’t have its own unique culinary personality. But, the countryside is where you continue to see the big differences. Rural Liaoning province, where I lived, is another food planet compared to a mountain village in Guizhou.

How do people tend to respond to two strange Americans wanting to come into their kitchens and make them food?

We're consistently astonished by the level of hospitality in China. Can you imagine walking into a nice restaurant in New York and asking to cook something in their kitchen? You’d likely be escorted to the nearest treatment center to have your head examined. It just wouldn’t happen here.

Before we turn on any camera, Greg and I are already talking to folks about our mission, to share cuisines across cultures and it’s always met with welcoming smiles. If we’re lucky enough to meet a chef or restaurateur, we respectfully propose feeding their staff and/or their diners. We are always shocked when they say yes. Sometimes we do have to get creative and cook al fresco and keep our fingers crossed.

For example, we decided to cook a luau at Bo’ao Beach on Hainan Island. Isn’t someone going to stop us from lighting a big fire? Turns out, much to our surprise, no. In fact, the locals brought us kindling. Really, this openness and hospitality is what keeps drawing us back. Well, also the amazing food.

On Sauced in Translation, Greg and I try to give the viewers a sense of not only the cuisine of China, but also the people involved in making it and eventually eating it. For those who may never travel to China, it’s an awakening that Americans and Chinese will bond over food. With any luck, however, the series also inspires others to visit China and do some Saucing themselves!