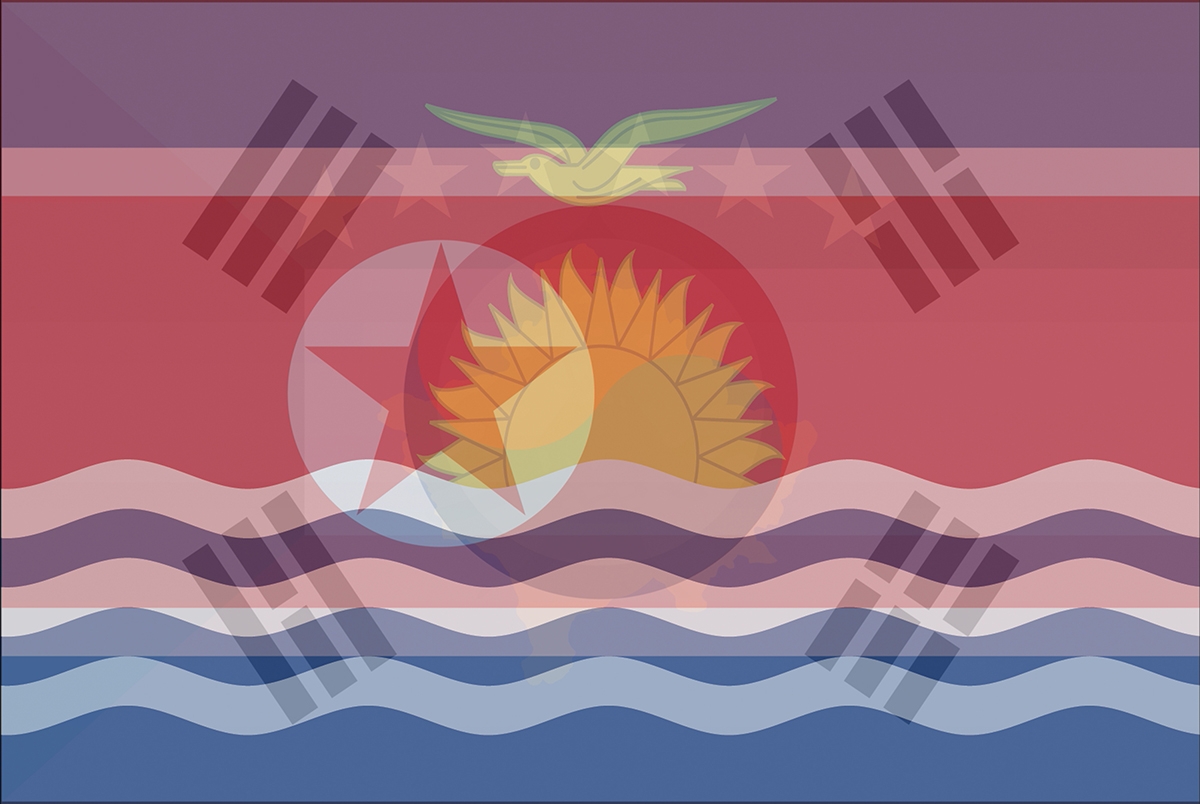

Wolak National Park. Photograph courtesy of the artist

-

Wolak National Park. Photograph courtesy of the artist

Dreaming With: Kimsooja

In the lead up to the Triennial opening, our Dreaming With Q&A series provides an exclusive glimpse into the artists’ lives and studios.

Where have you been during the lockdown?

I’ve been staying in Korea, between home and regularly visiting a hut in the mountains.

Is there anything you have found yourself cooking a lot of, and if so, would you be open to sharing the recipe with our readers?

I actually spent a lot of time in the kitchen preparing meals for my husband, who is on a liquid diet. It has been mostly porridges, vegetable juices, and soups that must be finely ground. I don’t have time to make anything interesting for myself and also don’t want to make any other smells at home.

What are you reading?

I am not a reader but also haven’t had enough time to read even a single book over the last six months, although I tried. I can only go online from time to time, in between taking care of many things at home. Instead, I can say I’ve been reading nature and contemplating it as I regularly spend time in Wolak National Park.

What music are you listening to?

Normally, I don’t make much effort to listen to a piece of particular music unless I have various selections to choose [from]. I enjoy all genres, including experimental music, but when I stay in the mountains I very much enjoy the jazz radio channel as it gives me so much freedom and provides a pleasant rhythm in nature. However, silence and the sound of nature is the best music of all. Listening to the wind, water, birds songs, and frogs...

Have you seen any particularly good digital exhibitions in the past few months?

Not really. I don’t like digital exhibitions except when it is created for a site-specific context.

What do you find yourself working on most during quarantine?

I've been contemplating non-stop on the vulnerabilities of life and the power of nature, planting some green vegetables in a small garden around the mountain hut while working long-distance on my exhibition at Wanås Konst in Sweden. This exhibition titled “Sowing Into Painting” involves a number of new site-specific installations about an acre of planted flax fiber and flax oil seeds that will be harvested in September to make linen fibers and linseed oils for oil paint; one hundred Swedish bedsheets to hang in the forest called “A Laundry Field”; a sound and a mirror installation called “To Breathe” and “Deductive Object” in a hay barn; and finally an installation that consists of linen canvas frames and Bottaris made of linen canvas called “Meta-Painting.” All of these installations have been completed without my presence during the pandemic by working long-distance, mainly via video calls. They wouldn’t have been realized without the Wanås Foundation and the curator’s dedication to my project, [along] with collective efforts made by the staff members and local volunteers.

Cultivating my own small garden [and] planting vegetable seeds is a modest way of [showing] my appreciation [for] participating in the “Sowing Into Painting” exhibition at Wanås Konst.

Photograph courtesy of the artist

How has your studio practice changed in recent months?

I moved back to Korea last year after living in New York for twenty years. Due to an urgent family situation, I still don’t have a physical studio and am working remotely from home. Fortunately, I am used to working remotely from traveling all the time, so it is not a problem working long-distance on large-scale, site-specific projects, albeit with great support from each institution and my studio members who are located in Paris, New York, and Seoul—it is not an issue to not have a physical studio and meetings regularly. And I am not an artist who makes things in the studio unless there is a conceptual necessity. We’ve worked efficiently from each of our homes on different continents. I think installation via video call has been working great, so far.

Have you created any art in response to the pandemic?

Although I planned the “Sowing Into Painting” exhibition at Wanås Konst before the pandemic, it now feels that it was a response to the COVID-19 as if I already knew the pandemic by instinct.

What artists most inspire you?

Rather than a particular artist or the artist’s practice, a particular statement by John Cage —“whether you try to make it or not, the sound is heard”—which he made in a piece in a container at the Paris Biennale in 1985. This statement has kept me contemplating “making art” and my practice of “non-making” and “non-doing” for the last thirty-five years.

What are you most looking forward to about participating in the upcoming inaugural Asia Society Triennial?

I have not been so keen on categorizing myself as an Asian Artist, so far, and refused to do so, but I have witnessed more and more that in New York, the art scene is so dominated by white, male artists and western artists, or artists chosen for a certain nationalistic perspective, I think it is an important act to uplift Asian artists as a minority, especially as an Asian artist who has lived in and contributed to New York City for over two decades, together with other Asian artists. This Triennial will give a clear voice to the New York art scene and beyond which didn’t find their deserved position as Asian artists in the historical context in the U.S.

What do you most want viewers to take away from experiencing your work in the Triennial?

It feels like the right time to present To Breathe - The Flags (2012) for the first Asia Society Triennial in New York in the midst of the pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement. [In this] piece, 246 national flags are slowly superimposed in alphabetical order, without hierarchical order or political bias, putting all nations on the same level: a visual experience in which differences and conflicts between nations can fuse and blend together as one. The piece was originally created for the 2012 London Olympics to reflect the unifying spirit of the games, although that first version only included the flags of participating countries. The flags added later represent nations that are not accepted or officially recognized by the authorities, such as North Korea. Overlapping the flags is a gesture of understanding, of fraternity among equals, of respect for differences. It is my hope for an ideal society, a utopia.

Has your perspective as an artist changed in the midst of the pandemic?

It made me contemplate a lot the vulnerability of humanity, the irony of being imprisoned by the mobility of our time, the power of nature and the truth, taking a pause from the sleepless art world. It made me ensure what I believe: ongoing fundamental questions and on “non-doing” and “non-making.”

Are there any fun facts about your practice you would like to share with readers?

“Living” as an art form can embrace any fun facts of life.