Photograph courtesy of the artist

-

Photograph courtesy of the artist

Dreaming With: Kyungah Ham

In the lead up to the Triennial opening, our Dreaming With Q&A series provides an exclusive glimpse into the artists’ lives and studios.

Where have you been during the lockdown?

We didn’t have lockdown in South Korea, but the social distancing policy had me staying at home most of the time. I went out for a scenic drive every once in a while to get some fresh air.

Is there anything you have found yourself cooking a lot of, and if so, would you be open to sharing the recipe with our readers?

South Korea is known for its efficient delivery industry, and I had also made good use of these order-in services. I eventually grew sick of the taste, however, and tried to have healthier eating habits by looking up recipes that kept the original flavor of the ingredients intact. As I have begun to pay more attention to how to cook, including careful maneuvering of heat and time, it’s become important for me to select the right cooking utensils.

Photograph courtesy of the artist

What are you reading?

John Berger

What music are you listening to?

I’ve been listening to a wide range of music, including traditional Korean music, pop, opera, Bach, etc.

Have you seen any particularly good digital exhibitions in the past few months?

I simply check out the exhibitions that send invitations to my inbox.

What do you find yourself working on most during quarantine?

It seemed like everything and everyone, including my studio and the people whom I collaborate with, were put into a not-so-temporary halt, except for the virus. The quarantine was an opportunity for me to fully rest without feeling guilty, and I tried to be as lazy as possible. It was a valuable time, indeed.

How has your studio practice changed in recent months?

My work is about surpassing both physical distance and ideological boundaries and taking detours as the process involves transactions with people I rarely know, trips to unknown places, and work by anonymous people. Chance and incompleteness, therefore, are vital components of my work. These are what had rendered the impossible possible, but today everything that was once possible has become impossible. Realistically speaking, routes to collaboration have been severed. I’ve been engaging in a lot of reversal thinking these days.

Photograph courtesy of the artist

Have you created any art in response to the pandemic?

As social distancing naturally forced me to be alone, I’ve been making a lot of drawings and collages, the kinds of practices that allow me to maximize the limited freedom that I have.

What artists most inspire you?

Artists who are original inspire me, and artists that I don’t want to be like give me the opportunity to self-reflect.

What are you most looking forward to about participating in the upcoming inaugural Asia Society Triennial?

My work has a tendency to jump back and forth between the boundaries of the physical and the abstract. I hope that New York, as a cultural and political center, will prompt different sets of lessons and dialogues, and eventually have us envision new boundaries and horizons.

What do you most want viewers to take away from experiencing your work in the Triennial?

To imagine what’s invisible, i.e. the process behind the work and its nature, and thereby complete the conceptual aspects of the work.

Has your perspective as an artist changed in the midst of the pandemic?

Yes and no. The pandemic made me deeply think about the society I live in, our values, time, nature, and so forth, as a human being rather than an artist.

Photograph courtesy of the artist

Are there any fun facts about your practice you would like to share with readers?

There are two episodes I want to share.

First episode:

From time to time, the embroidery would arrive shaped like a rhombus rather than a rectangle. It had to do with the different force used to pull the fabric by each artisan. Upon my urge to make the corners straight for these works, I was told: “You must understand! These kids (embroideries) have survived through the turmoil of life!”

Second episode:

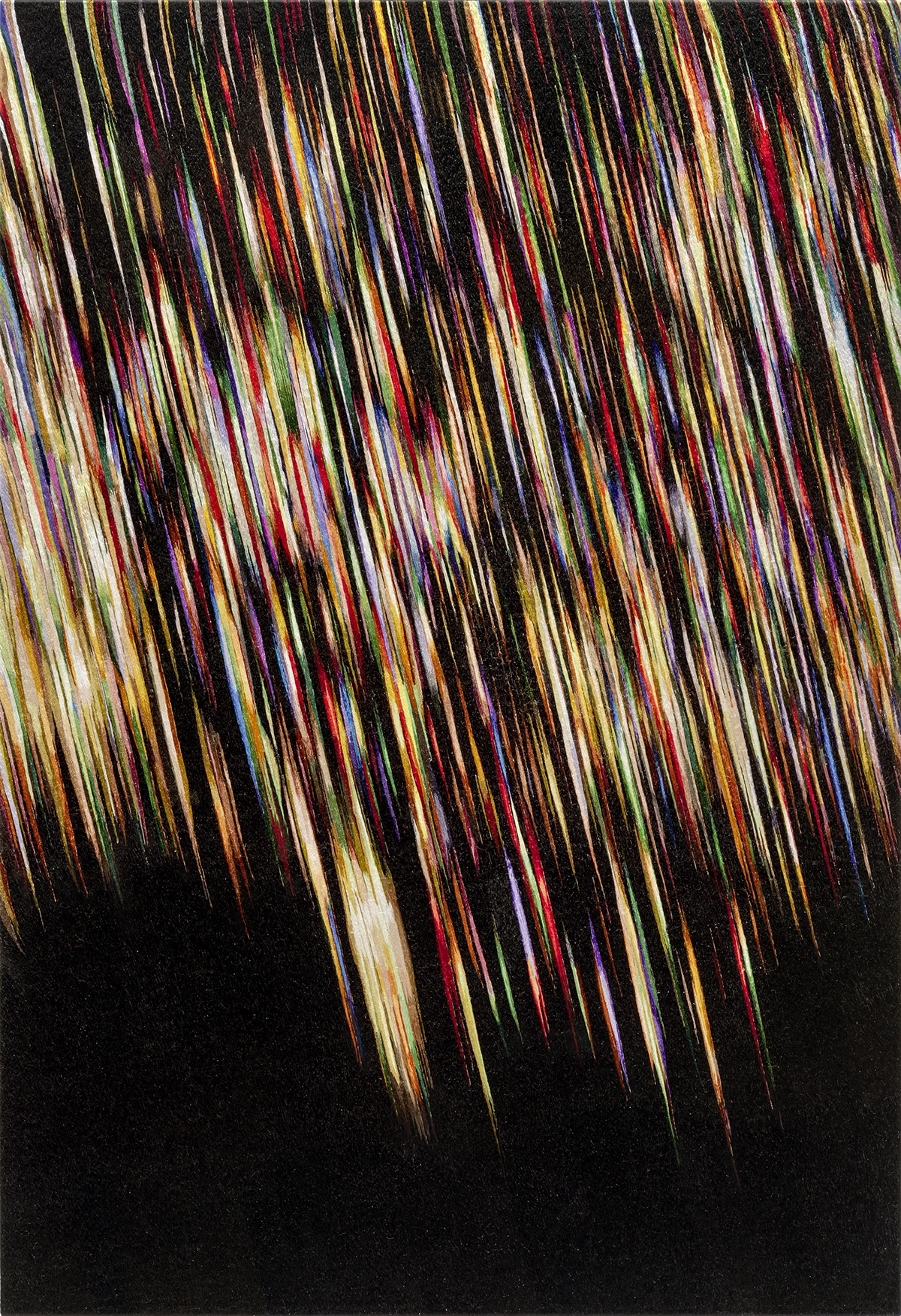

Once the embroideries are finished, I would meet the intermediary at a third country to receive them. The intermediary would then note the problems or comments in a letter and send it back to North Korea by a person. In order to protect themselves from getting caught over these smugglings, they came up with a secret code. As the intermediary was engaged in a medical business, they would employ the names of drugs to avoid any suspicion. For instance, when you say “failed to get Vitamin A from China,” it meant “there was a problem with the work we decided to refer to as Vitamin A.” And so, these embroideries began to bear names such as calcium, Trental, and other nutritional supplements and stroke medications from Russia, Japan, and the U.S. I eventually decided to adopt these secret codes in the titles of the works: Trental fluttering its wings gracefully, Big and Pretty Eyes Wink at Arinamin…