Xi the Survivor: How Washington Overestimates Chinese Weakness

Foreign Affairs

The following is an excerpt from Asia Society Policy Institute's Center for China Analysis Senior Fellow on Domestic Politics Christopher Johnson's article originally published in Foreign Affairs.

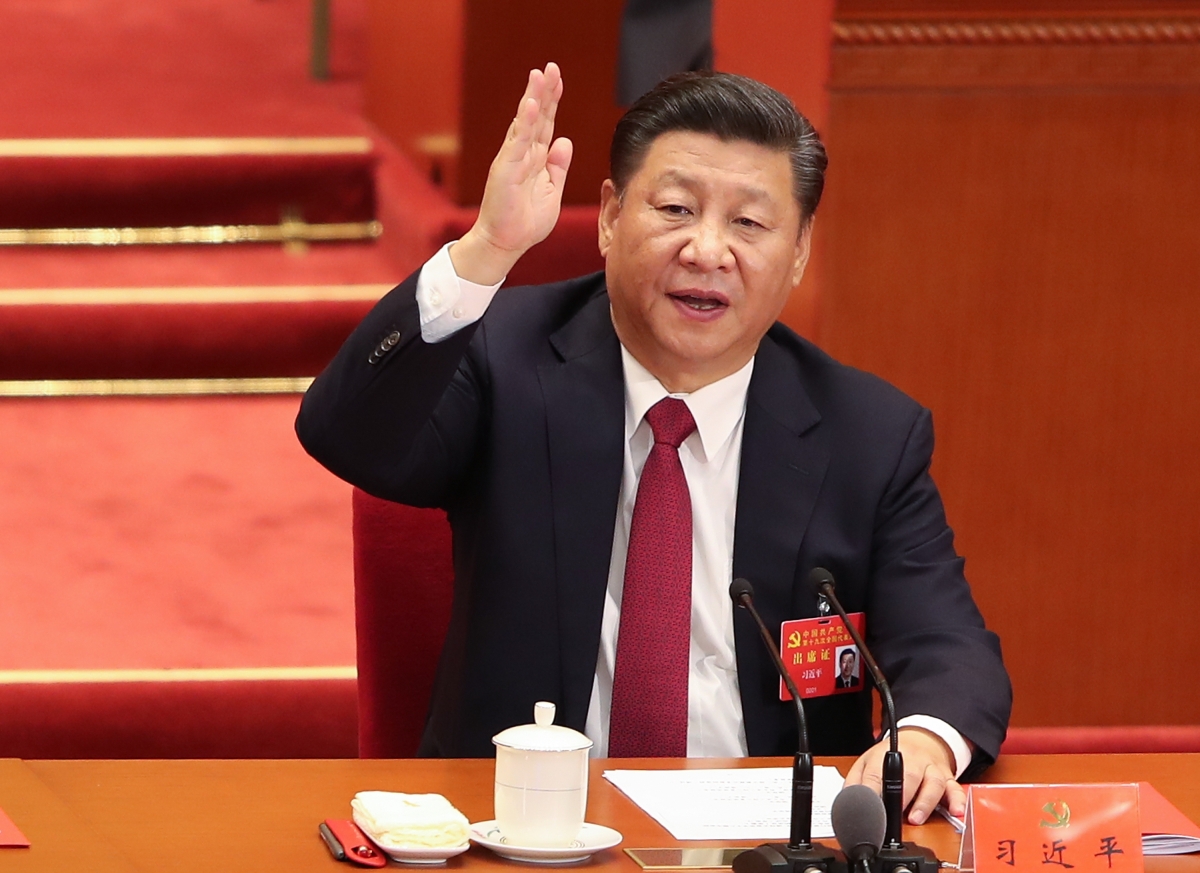

After Chinese President Xi Jinping secured a historic third term in October 2022, many Western analysts heralded him as a modern-day emperor. But just four months later, a glance at the headlines suggests he is under pressure at home and his grip on power may be looser than many thought. A messy exit from China’s “zero COVID” policy and a rogue spy balloon — allegedly the work of a Chinese military seeking to prevent Xi from stabilizing relations with Washington — are seen by some observers as evidence that the Chinese leader is suddenly on the back foot. But such analyses ignore both Xi’s ruthless political cunning and his efforts to better manage the intrinsic pathologies of a system whose flaws are viewed by Chinese Communist Party (CCP) magnates as acceptable risks as long as they remain in power.

A hallmark of Xi’s rule has been his propensity to make big bets that he thinks will pay off for him and for China. At the very beginning of his tenure, he launched a withering anticorruption purge that decimated once mighty barons of the Politburo, military, and security services. Many analysts thought such a move would be impossible at the time: they presumed that Xi was constrained by powerful interest groups, just as his two predecessors had been.

But Xi quickly outmaneuvered those alleged kingpins, allowing him to launch a transformative policy agenda comparatively early in his rule. What followed were other big bets, including his risky gambit to deleverage China’s debt-plagued financial sector, his unapologetic stance on the world stage, and his claim that China has a unique and effective development model — what Xi calls “Chinese-style modernization” — that may work for others. Western analysts roundly condemn these innovations as ruinous for China and threatening to other countries. But the hard truth is that it is too soon to make such confident judgments.

Most of Xi’s big bets have one thing in common: they keep his adversaries, both domestic and foreign, off balance. As a Leninist organization overseeing a continual revolution rooted in so-called contradictions and struggle, the CCP lacks, and even eschews, the legitimacy democratic systems derive from their institutions or from shared beliefs such as constitutionalism. In Xi’s eyes, that makes China’s bureaucracies possible rival centers of power, incentivizing him to keep them decoupled from — and perhaps even at odds with — one another.

But isolating the bureaucracies too much risks germinating autonomous fiefdoms that are only nominally loyal to their party masters. This dilemma has plagued each of China’s leaders since Mao Zedong, but Xi has turbocharged it with his obsessive emphasis on party dominance. His solution, “political shock and awe,” mixes raw power with new institutional arrangements that bolster that power. Because it keeps China’s major security organs under stricter civilian control, this developing approach may make Beijing less dangerous than those pushing the narrative of a new cold war with China want to acknowledge. Unfortunately, it will take patience, confidence, and a steely commitment to a China policy rooted only in the national interest to find out — all of which are in short supply in today’s Washington.

Read the full article in Foreign Affairs.