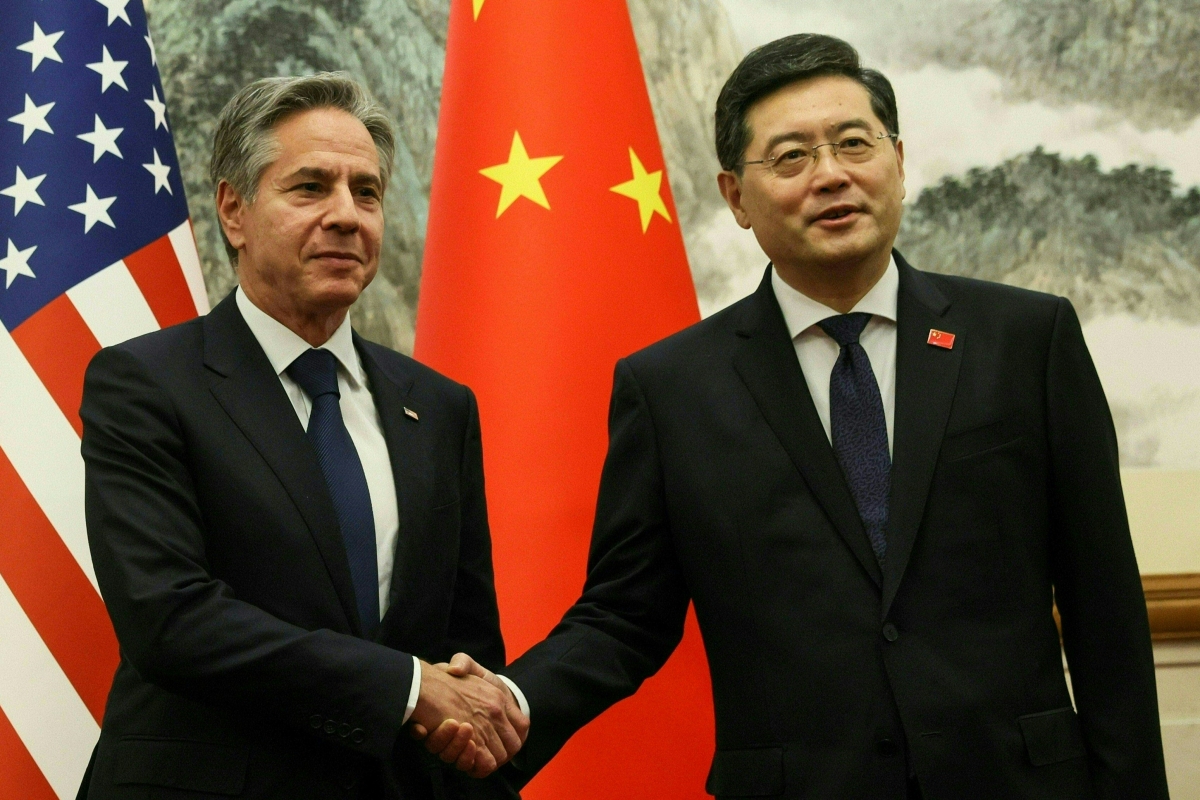

What Could Happen Now That Qin Gang is Out as Foreign Minister?

On July 25, the Chinese government removed Qin Gang as foreign minister and selected Wang Yi as his replacement. Qin served for less than seven months, while Wang returned to an office he held from March 2013 until Qin’s appointment in December 2022. Qin retains his role as a state councilor, a higher-ranking position with more inward-facing responsibilities.

Qin has not appeared in public since June 25. Beijing offered no updates this week about his whereabouts, his physical condition, or his political standing. That he remains a state councilor and was “removed” (mianzhi) rather than “dismissed” (chezhi) as foreign minister could indicate Qin is simply too ill for diplomacy. But his unexplained absence and relatively uncensored rumors about Qin also suggest he could be under political investigation, in which case he could hold his other roles until its conclusion.

We cannot confirm Qin’s situation. But we can explore the possibilities for how Beijing will respond in the medium term to the personnel issues that arise from his potential physical or political incapacitation. Who will succeed Wang Yi as foreign minister? Who might replace Qin Gang as state councilor? These are significant questions for the Communist Party and its General Secretary Xi Jinping.

Wang’s reappointment as foreign minister is likely a temporary arrangement. His top priority will be to manage the ongoing stabilization of U.S.-China relations and Xi's expected visit to the United States this November for the APEC summit in San Francisco. But Wang can only lead the party’s Central Foreign Affairs Office (CFAO), his main job since the 20th Party Congress last October, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) for so long without straining China’s diplomatic capacity. That may be less of a concern to Xi than reestablishing stability, but an extended tenure for Wang back at MOFA would further rattle the expectations of China’s emerging diplomatic leaders.

Qin’s promotion made him the heir apparent to Wang as China’s top diplomat at the 21st Party Congress in 2027. Wang, who turns 70 this year, sits on the party’s elite 24-member Politburo as the CFAO director but should retire in four years. Whoever now follows Wang as foreign minister is also likely to take his Politburo seat at the next party congress, a weighty prospect that could have contributed to the decision to reappoint Wang, at least for now. It is possible Qin returns as foreign minister, particularly if he is recovering from sickness, but Xi has several other options.

Liu Jianchao is perhaps the likeliest candidate because he has the strongest ties to Xi. He spearheaded Xi's campaign to track down corrupt officials abroad as a deputy director of the former National Bureau of Corruption Prevention (2015-2017), worked as discipline chief of Xi's old power base in Zhejiang Province (2017-2018), and was a CFAO deputy director for several years (2018-2022) before attaining ministerial rank as the current director of the party’s International Department. He started as a career diplomat, studied international relations at Oxford University, and served as ambassador to the Philippines and then Indonesia before working as a MOFA assistant minister. He is also a full member of the party’s Central Committee. He would bring diplomatic experience and political nous to the role.

Liu Haixing is another former diplomat with strong ties to Xi but may be too valuable in his current position. He is a bureaucratic powerbroker in national security policymaking through his longtime role as a deputy director in the general office of Xi’s powerful Central National Security Commission (CNSC). He was at the MOFA from 1985 until 2017, where he specialized in French and European affairs, leaving as an assistant minister. Liu, like Xi, is the “princeling” son of a senior official — his father, Liu Shuqing, was a deputy foreign minister from 1984 to 1989 and secretary-general of what is now the CFAO from 1989 to 1991. He was promoted to ministerial rank last year and is also a full Central Committee member.

Ma Zhaoxu is a continuity candidate from within MOFA whose promotion would probably prove most popular within the ministry but could limit its political influence. He is the ministerial-level executive deputy foreign minister, who runs the ministry’s day-to-day business. Ma became a deputy foreign minister in 2019, after stints as China's ambassador to Australia and then to the United Nations in first Geneva and then New York. He is one of Beijing's most experienced multilateral diplomats, and his elevation would support Xi's drive to strengthen China's influence in global governance. He lacks strong ties to Xi, however, and is not a Central Committee member.

Deng Hongbo is an outside chance. He works for Wang as a deputy director of the CFAO but is still only at the deputy-ministerial level and is a protégé of Wang’s predecessor, Yang Jiechi. Deng is an “America hand” who worked under Yang for several years at the Chinese Embassy in the United States and then at the CFAO. Neither he nor Sun Shuxian, the other CFAO deputy director, are on the Central Committee.

Of course, Xi may surprise us again. He could restore a disciplined Qin as a chastened but even more devoted foreign minister. He could choose a left-field candidate, like MOFA Party Secretary Qi Yu, who has no diplomatic experience, or a more junior diplomat who made an impression on him. Xi’s bending of promotion and retirement norms has made personnel appointments increasingly difficult to predict.

If Qin is charged with violating party discipline, Beijing will almost definitely rescind his state councilor position. This could be done by the National People’s Congress Standing Committee — the body that removed Qin as foreign minister, which usually meets bimonthly — or when the full NPC meets in March. Investigations into high-ranking cadres can take several months or even years. Should the Central Committee eject Qin at its Third Plenum, likely to convene in October, we will know this is coming.

A wide range of officials could conceivably succeed Qin as state councilor. Xi may decide to follow recent convention and appoint the next foreign minister to the State Council. Another alternative is an official from the security apparatus, especially given Qin’s early career in intelligence agencies and speculation he is caught up in a spying scandal. An intriguing possibility is that Xi could use this vacancy to elevate Chen Yixin, the Minister of State Security and one of his closest allies, to deputy-national rank.

The most important part of China watching is knowing how much we do not know. The greatest certainty about the Qin Gang affair is we will not know more until the party decides to tell.