Listen: Kevin Rudd on the China-India Relationship and Its Regional and Global Implications

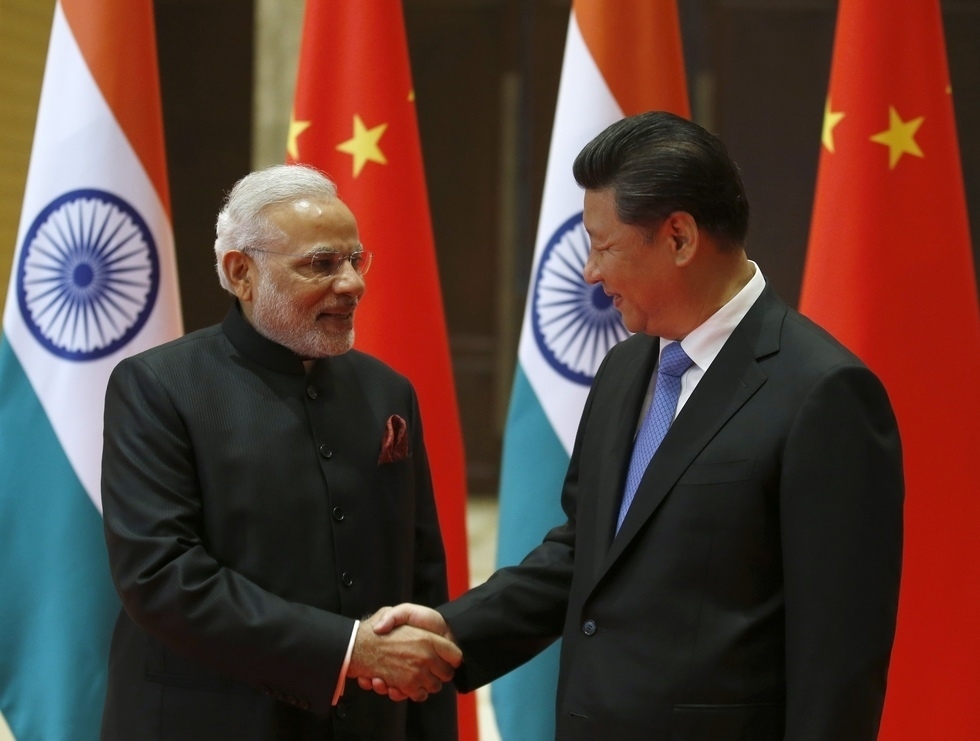

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to China in May marked the second time in less than a year that he and President Xi Jinping of China held summit-level meetings in their home countries. In an AsiaConnect briefing on June 4, 2015, ASPI President Kevin Rudd presented his views on the summit, the China-India relationship, and the influence of this relationship on regional affairs.

This page presents excerpts from Rudd’s remarks. The entire briefing can be replayed from the audio player below.

India looks at China: Three concerns

From India’s perspective, the border dispute remains central. This has been in existence from the beginning of Indian independence and the assumption to political power by the Chinese Communist Party two years later in 1949. And to this day, it overshadows the relationship. […]

The second dynamic in the security domain between India and China has to do with India’s western neighbor, Pakistan, and by extension, the broader security dynamics of Afghanistan. From an Indian perspective, Chinese cooperation with the Pakistani military over a long period of time, particularly in terms of the evolution of the Pakistani nuclear program, has left a very, very deep and negative set of sensitivities in New Delhi about China’s long term aspirations for strategic stability in the China-India Relationship.

In relation to that, of course, and beyond the nuclear program in Pakistan, is concern, from New Delhi’s perspective, about the threat to Indian domestic security from individuals associated with the Pakistani state, directly or indirectly in India’s allegation, in terrorist activities within India itself. These, of course, reached their crescendo at the time of the horrendous attacks on Mumbai not that many years ago.

If there is a final dimension in the China-India relationship which concerns Delhi, it is China’s increasing move into the Indian Ocean.

India’s need for Chinese capital investment

In my own discussions in Delhi during a number of visits in recent times, it’s quite plain that one of the core challenges facing the economic reform program in Delhi is to ensure that there is new sources of investment into India’s overall extraordinary infrastructure investment deficit. This covers all branches of infrastructure, whether it’s in transport, communications, and telecommunications—transport in particular. […]

Given the complexities of India’s domestic legal system, how is such capital to be obtained? From domestic investors within India or from abroad? From the United States and the rest of the international community? Or from new potential sources of investors, such as China? This is very much the prism through which Prime Minister Modi approached his visit to China. […] If you read the tea leaves in the various statements, observations, and agreements outlined during the visit by Prime Minister Modi to Beijing, it’s quite plain that this Chinese prospective investment in India in general, and in the rail network in particular, remains a core priority.

Easing the China-India border dispute

Prime Minister Modi reiterated that the two countries must try to settle the boundary question quickly and to transform the overall relationship. How this unfolds in the period ahead remains to be seen. I think strategic and economic realists in Beijing, mindful of the evolving U.S.-India relationship, may well be inclined towards a more proactive approach to resolving the border question than we’ve seen in the period of previous Indian administrations.

It is fair to say as a consequence of this visit that no substantial progress was achieved on the border. But the language contained in the joint statement of the visit indicates that this will not simply be pushed to the back burner, but be the subject of a more proactive approach from both sides.

The China-India relationship across the region

I think most countries in South Asia that I am familiar with would wish to maintain a balanced relationship both between Delhi and Beijing. Certainly Beijing, when it’s observed the electoral results in Sri Lanka, have not thrown their hands up in horror, and said, “Well, that’s the end of the Sri Lankan relationship.” The Chinese have said, “Well, we must learn from this and rebuild our relationship with the Sri Lankan administration.” And certainly when I was at the at the Boao conference in China in March this year, I noticed one of the keynote addresses being given by the newly elected president of Sri Lanka, there as a guest of president Xi Jinping. And so China’s approach to difficulties in bilateral relationships is to learn from them, and nonetheless to keep the level of engagement going into the future.

So from regional countries’ point of view, I think their interest is to maintain balance between the two. I don’t think from Delhi’s perspective they wish to see a bifurcated region of countries more aligned to Beijing in one department, and more aligned to Delhi on the other. But it does leave the broader strategic question in play as to how India and China will now, at the level of naval operations, cooperate or otherwise in the wider Indian Ocean, given China’s stated interest, through its naval operations, to protect and defend its global interests.