The End of Experimentation and Aspiration in Xi Jinping’s China

This paper is the first in a two-part series exploring how the leadership of Chinese President Xi Jinping has changed the fundamental incentives driving the behavior of key groups in China and beyond. The second paper will focus on international responses to Xi’s “new era.”

Over the past 40 years, betting against the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has been a fool’s game. But today, China’s development model faces its most formidable test. During Xi Jinping’s ten years in power, he has overseen major economic and political changes that threaten to undermine the key drivers of China’s success during the “reform and opening up” era. Instead of an open, pragmatic, and experimental approach to development, Xi has turned to national security, ideology, and top-down directives to realize his “China Dream” of national rejuvenation.

Most importantly, Xi has fundamentally changed the incentives driving the behavior of local government officials, private entrepreneurs, and young Chinese, plunging China into uncharted, stormy waters.

During his first two terms, Xi relied on a relentless and widespread anti-corruption campaign to become master of all he surveys. This campaign was not just a purge orchestrated for political gain, but also a genuine effort to eradicate the pervasive corruption that threatened the Party’s survival. Xi systematically rebuilt the authority and image of the Party among ordinary Chinese and extended its reach into every corner of their lives.

But as China’s paramount leader, Xi has taken a path closer to Mao the strongman than to Deng Xiaoping the pragmatist. Xi’s overwhelming victory at the 20th Party Congress in late 2022 ensured that he is here to stay for at least a third term — and likely a fourth — as his allies now enjoy uncontested control over the top echelons of the Party.

Anti-Corruption Campaigns, Top-Down Directives, and Policy Experimentation

Despite his unmitigated political victory at the 20th Party Congress, Xi has no intention of rolling back the anti-corruption campaign, which has become integral to his exercise of power and possibly the only real success of his tenure so far. Xi is unlikely to release his grip on the reins of administration.

But Xi’s centralization of power and anti-corruption campaign now threaten one of the most successful aspects of China’s development model: the formulation of policy by trial and error, or, to use Deng Xiaoping’s famous phrase, “crossing the river by feeling the stones.”

China’s decisive swing toward top-down directives under Xi is now threatening to stifle local experimentation, at best making it ineffective under the pressure of conflicting central government objectives, and at worst causing local-level paralysis.

Deng’s decentralizing reforms and focus on growth granted localities more authority and pitted local officials against each other, giving them incentives to experiment. Once the Party’s top leaders reached broad agreement about the objectives of a particular reform, Beijing’s “try-it-and-see” approach created space at the local level for initiative and innovation. Running local pilot schemes, encouraging experimentation, and exploring solutions tailored to specific circumstances before rolling policies up to the provincial level and then nationwide allowed China to scale up and industrialize at breakneck speed.

This mode of development had some drawbacks. The focus on growth at all costs came at the expense of the environment while encouraging competition among local governments without enforcing hard budget constraints led to years of overinvestment. The global financial crisis and weak global demand that followed exposed cracks in the edifice of China’s towering economy. By 2012, it had become clear that the huge monetary stimulus Beijing was throwing at the problem was not the solution. Amid an escalating ratio of overall debt to GDP and slowing growth, Xi began his first term with an expectation that the economy needed a major overhaul.

In the context of Beijing’s disillusionment with the United States’ economic management in the wake of the financial crisis, and a hardened belief in the superiority of its own ways (both unwarranted, in this author’s analysis), it is understandable that Xi chose to double down on state control and the re-centralization of decision-making power.

Yet China’s decisive swing toward top-down directives under Xi is now threatening to stifle local experimentation, at best making it ineffective under the pressure of conflicting central government objectives, and at worst causing local-level paralysis.

In an ever-more complex environment, and under conditions of increasing uncertainty in which “what works” is unknowable in advance, undermining the potential for local trial and error in China’s development model bodes ill for its future success.

It is difficult to test this hypothesis empirically, and no study, whether theoretical or practical, has proven definitive in this regard. On the face of it, one could argue that by pushing through the center’s directives more effectively, Xi has actually bolstered experimentation, which he has portrayed from the start as an essential attribute of a “good cadre.” The Central Committee’s 2019 notice on cadre evaluation states that officials who do not “display enough entrepreneurial spirit” and those who are “afraid to face contradictions or unwilling to get into trouble” will not receive positive evaluations or promotions.

But experimentation under pressure when inaction may be punished as corruption does not ensure that such initiatives will be effective. This approach may increase the quantity of experiments, but it is more likely to decrease their scope and quality. In 2021, despite referring to pilot projects as the “most effective” policymaking method, Xi also criticized “show-style” experimentation and “grandstanding.”

Local officials today are losing the ability to act independently, making their own decisions about which experiments to conduct and how to prioritize them. Moreover, as the easy gains of catch-up growth have evaporated and China’s economic reality has become more complex, local officials are faced with more and more conflicting directives from the top. The mood of political paranoia as a result of rolling purges has left local officials terrified of pushing the envelope, lest rivals use their risk-taking as an excuse to end their careers. Meanwhile, rigorous Party discipline inspections are more likely to cause local government paralysis than not.

In an ever-more complex environment, and under conditions of increasing uncertainty in which “what works” is unknowable in advance, undermining the potential for local trial and error in China’s development model bodes ill for its future success.

To get Rich is no Longer Glorious

Another key feature of Deng’s reform era was the creation of incentives for the private sector to flourish. Deng accepted the capitalist class with a pragmatism worthy of marvel, both then and now, in contrast with the Soviet bloc. His two successors, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, continued to marry Marxism with wealth creation.

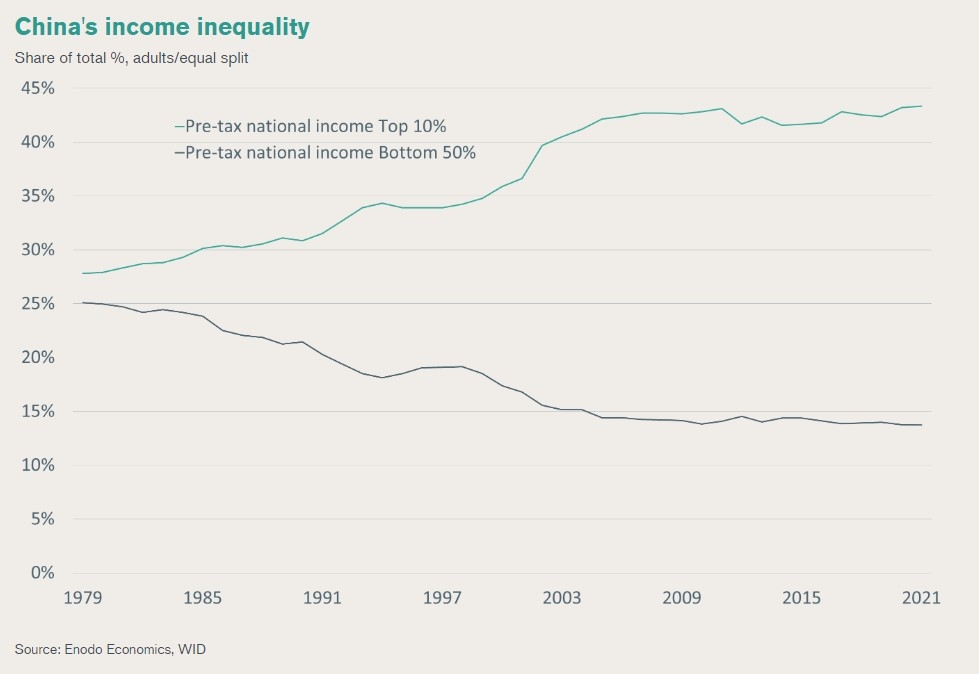

Xi, however, looks to ideology, not pragmatism, to deliver what he genuinely believes is necessary to maintain China’s social cohesion: a nation that is not only prosperous but also egalitarian.

Fighting income and wealth inequality is a noble task, but Xi’s approach has undermined an even more important driver of development over the past 40 years: private entrepreneurial spirit.

Xi Jinping’s watchword is frugality. Even more importantly, he is determined to address China’s gaping inequality.

In a watershed moment in August 2021, Xi added the goal of “Common Prosperity” to Party doctrine, updating a concept from China’s Maoist past to put reduction of inequalities, expansion of the middle class, and support for small and medium-sized companies at the heart of China’s economic policies.

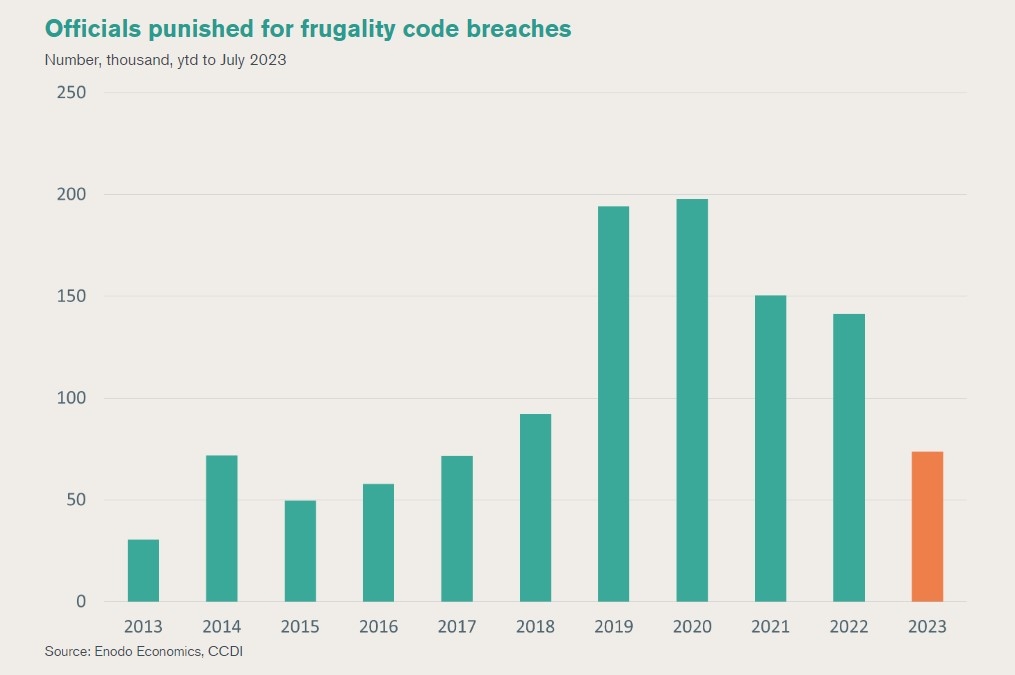

From the outset of his rule, Xi has singled out lavish lifestyles and ostentatious spending as targets for criticism. The Party’s top anti-graft body has punished more than a million officials since the eight-point frugality rules came into effect in 2012.

Xi Jinping’s watchword is frugality. Even more importantly, he is determined to address China’s gaping inequality.

While China has certainly become a manufacturing powerhouse since its entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001, it has also become one of the most economically unequal countries in the world — not a record to boast about in the same breath as “socialism with Chinese characteristics for a new era.”

Deng envisaged “common prosperity” as naturally following from industrial catch-up. When he was asked during a rare interview for the U.S. news program 60 Minutes in 1986 to square his slogan “to get rich is glorious” with communism, he said,

So to get rich is no sin. However, what we mean by getting rich is different from what you mean. Wealth in a socialist society belongs to the people. To get rich in a socialist society means prosperity for the entire people. The principles of socialism are: first, development of production and second, common prosperity. We permit some people and some regions to become prosperous first, for the purpose of achieving common prosperity faster. That is why our policy will not lead to polarization, to a situation where the rich get richer while the poor get poorer.

In Xi’s view, such a policy is insufficient. To narrow the gap between rich and poor, Xi seeks to reverse excessive income accumulation and stop house price inflation. Policymakers have used taxation and government transfers to redistribute income and adjusted wage levels in state-owned firms. Beijing explicitly “encourages” high-income private firms and individuals to contribute more to society through the “third distribution” of charity and donations.

This fundamental change has altered the incentives of many well-off and middle-class urbanites, pushing Chinese households to save even more.

Sky-high house prices, in particular, are widening the divide between rich and poor, and Xi has intoned the mantra that “houses are for living in, not for speculation” since the 19th Party Congress in 2017. However, it was not until August 2020, when the authorities introduced the “three red lines” measures aimed at reining in indebted property developers, that the housing market gave way and Chinese households and markets began to get the message that Xi means business on bringing down house prices.

Property is the main asset for middle-class Chinese families. In cities, families hold apartments for capital gains, not for rental income, as the rental market is underdeveloped. Often, they do not even kit out the investment properties they buy, which sit unoccupied. Beijing proposed to make productive use of these idle properties by developing the rental market, but these efforts have not borne fruit so far. As a result, households lack income from their investment properties, and they can no longer rely on capital gains to grow their wealth.

This fundamental change has altered the incentives of many well-off and middle-class urbanites, pushing Chinese households to save even more.

This bodes ill for the Party-state’s goals to rebalance the economy toward consumer spending and to grow the overall income pie.

The Party Subjugates the Private Sector to its Needs

Xi has never believed in the “trickle-down effect” of wealth creation. A straight-laced Marxist at heart — and one who spent his formative teenage years on a commune — Xi has never been comfortable in the company of tycoons and businessmen.

As entrepreneurs like Alibaba’s Jack Ma and others have long feared, Xi tolerates the private sector only as long as it serves the state’s interest. Large private firms have often strayed from that path.

Xi’s ideological goal is nonetheless to strengthen Party power in both state-owned and strategically important private enterprises, and to subordinate business decisions to the needs of the Party.

Private entrepreneurs in China achieved a breakthrough political recognition from Beijing in the late 1990s under the “Three Represents” theory, which allowed capitalists to become Communist Party members. That emancipation of thought unleashed private entrepreneurship, providing another key component of China’s growth engine.

But, over the past few years, Xi has clamped down on big private sector companies, which he regards as a threat to the Party’s monopoly on power, in addition to hoarding the nation’s wealth and valuable data. In the name of “common prosperity,” Xi has subjugated China’s big technology firms to the will of the Party, wiped out the private tutoring sector completely, and gone after the “disorderly expansion of capital” in the property sector and, more recently, in the financial sector.

Discrimination against the private sector has deep roots, despite its success and critical role in China’s development. Anti–private sector sentiment under Xi culminated a few years ago, when some Chinese scholars began to say publicly that “the historical mission of China’s private economy has been completed” — meaning that it no longer had reason to exist.

Official policies are not so extreme, but Xi’s ideological goal is nonetheless to strengthen Party power in both state-owned and strategically important private enterprises, and to subordinate business decisions to the needs of the Party.

Ultimately, why would business owners want to succeed when spending how one wants is frowned upon and hard-earned gains could be taken away to serve the needs of the Party?

True, part of the “common prosperity” described by Xi is to create space for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which account for 80% of urban employment and encourage getting rich through hard work and innovation.

For years now, the central authorities have been trying to ensure that SMEs have better access to credit, with mixed results. Former Premier Li Keqiang’s signature policy initiative — one that Xi has repeatedly endorsed — has been to reduce fees and cut red tape for entrepreneurs to start businesses. “Common prosperity” in that sense is nominally pro–private sector. So although Xi sees large private firms as both a barrier to “common prosperity” and a challenge to Party authority, he views development of small private firms as a way to distribute wealth more equitably, which should be encouraged.

Xi might be striving for a private sector that looks similar to Germany’s Mittelstand: a large stable of small private firms that are innovative, generate high-paying jobs, and produce technologically advanced manufactured goods. However, such a transformation will prove difficult when Xi’s mantra is frugality and redistribution.

Ultimately, why would business owners want to succeed when spending how one wants is frowned upon and hard-earned gains could be taken away to serve the needs of the Party?

In any case, the strategy has not worked so far, plunging the economy into the doldrums and causing policymakers to reverse gears. Chinese authorities published a major policy document to shore up confidence in the country’s private sector in July, with the Party pledging to build the nation’s private economy “bigger, better, and stronger.”

Beijing wants domestic private investors to participate more in both local and major national projects. But firms will question not only the likelihood of profitability, but also the sincerity of authorities. Businesses remain doubtful of Beijing’s promise to allow the private sector to grow amid the government’s focus on security and absolute control.

China’s Youth Lying Flat in the Face of Pressure and Growing Societal Disconnect

The most disconcerting shift in Chinese economic incentives is the disillusionment of the country’s youth, who have always played a pivotal role at key inflection points in China’s modern history.

Last year’s “white paper” protests, which toppled Xi’s “zero-COVID” regime, brought into stark relief the growing disconnect between the aspirations and values of the country’s youth and the expectations of the Party-state.

The Chinese Party-state is keenly aware of the destabilizing potential of China’s educated youth. But how well it can walk the fine line between meeting their aspirations and ensuring their compliance with Party objectives remains to be seen.

Demonstrations are, of course, nothing new in China, but most are local and driven by local issues. The November 2022 protests, in contrast, took place nationwide and were directed at the apex of power. Though widespread, the demonstrations never reached a critical mass. But they undoubtedly catalyzed the dramatic reversal in the zero-COVID policy. The leading role that educated youth played in the demonstrations also raised concern among the Party leadership, as they expanded their focus beyond COVID restrictions to address wider issues of freedom of expression and censorship. Predictably, the protesters were identified, rounded up, and detained, though many have since been released. But Beijing’s problems do not stop there.

The challenges facing China’s young college-educated generation have multiplied. Mostly only children, they are burdened by their parents’ expectations to excel academically and secure well-paid, high-status employment. In reality, their working lives are disappointing and frustrating, involving low pay and long hours of often unproductive activity — the so-called 9-9-6 model of working from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., 6 days a week. This has given rise to an urban counterculture called 丧文化 (sang wenhua) — “loser culture” — in which adherents refer to themselves ironically as 屌丝 (diaosi) — literally, “pubic hairs.” Other popular tropes symbolizing this movement are 躺平 (tang ping). “lying flat,” and 摆烂 (bailan), “letting it rot.” The essence of this counterculture is the rejection of aspiration and the embrace of a minimalist lifestyle supported by casual labor.

It is hard to estimate how widespread this countercultural movement has become; in practice, it may not be that significant. But its emergence has caused concern for a Party-state seeking to project a message of positive energy, productivity, and relentless optimism. Stern editorials in China’s official media excoriate those who seek to drop out of society.

The most pressing challenge facing China’s urban youth is the growing and probably intractable level of unemployment among college graduates. A number of factors — the slowdown in China’s economy due to COVID and the lackluster post-COVID recovery; the closure of many smaller private companies during the pandemic; and Party-state measures to curb the “disorderly expansion of capital,” particularly among digital service providers, real estate sector firms, and private tutoring companies that previously employed many young graduates — have contributed to a significant tightening of the urban labor market.

Add to that a significant demand for jobs: the number of college graduates soared to 11.6 million in 2023, a 40% increase from 2019, and it is predicted to reach 20 million by 2025. Paradoxically, there is no overall shortage of jobs: China’s manufacturing sector has a high level of vacancies, estimated to reach 30 million by 2025. But Chinese intellectuals have traditionally seen manual labor as beneath them, and this view persists among young college grads. Instead, graduates expect to get white-collar jobs and show little interest in working in factories or seeking work in the countryside, as the Party encourages.

This situation is perceived as a throwback to the Cultural Revolution, when large numbers of urban educated youths were rusticated to learn from workers and peasants. President Xi has repeatedly exhorted young people to “seek hardships” — as he is purported to have done as a youth — including in a recent state media article emphasizing his suffering during the Cultural Revolution.

The Chinese Party-state is keenly aware of the destabilizing potential of China’s educated youth. But how well it can walk the fine line between meeting their aspirations and ensuring their compliance with Party objectives remains to be seen.

Conclusion

As the economist Steven Landsburg observed, “Most of economics can be summarized in four words: ‘People Respond to Incentives.’ The rest is commentary.”

In Xi’s China, the incentives influencing behavior have changed fundamentally, undermining the key drivers of the country’s economic success during the Deng-Jiang-Hu period.

Despite Xi’s rhetoric about the need for experimentation, his centralization of power through a relentless anti-corruption campaign is sapping local officials’ appetite for Deng’s trial-and-error approach. Private entrepreneurs, another key growth engine, have seen their wings clipped by the Party for threatening to become “too-big-to-challenge.”

Xi’s flagship “common prosperity” campaign — a continuation of Deng’s ultimate vision for socialist China — so far has only undermined the confidence of China’s well-off urban middle class rather than boosting the spending of the less well-off. Meanwhile, Xi’s focus on frugality and hardship rings hollow for China’s youth, whose experience and aspirations are at odds with his turgid ideology.

China needs innovation to help it meet the challenges of a maturing economy, with aging demographics and an overhang of debt and wasteful investment. But for local bureaucrats, private entrepreneurs, and young people alike, the best response has been to keep their heads down and “lie flat.” Across too much of the Chinese economy, the go-go days of experimentation and growth are over. In this new, more ideology-driven China, everyone must adopt a more timid and cautious strategy — at the risk of derailing the country’s future.