The Coronavirus and Southeast Asia: Can Catastrophe be Avoided?

By Richard Maude

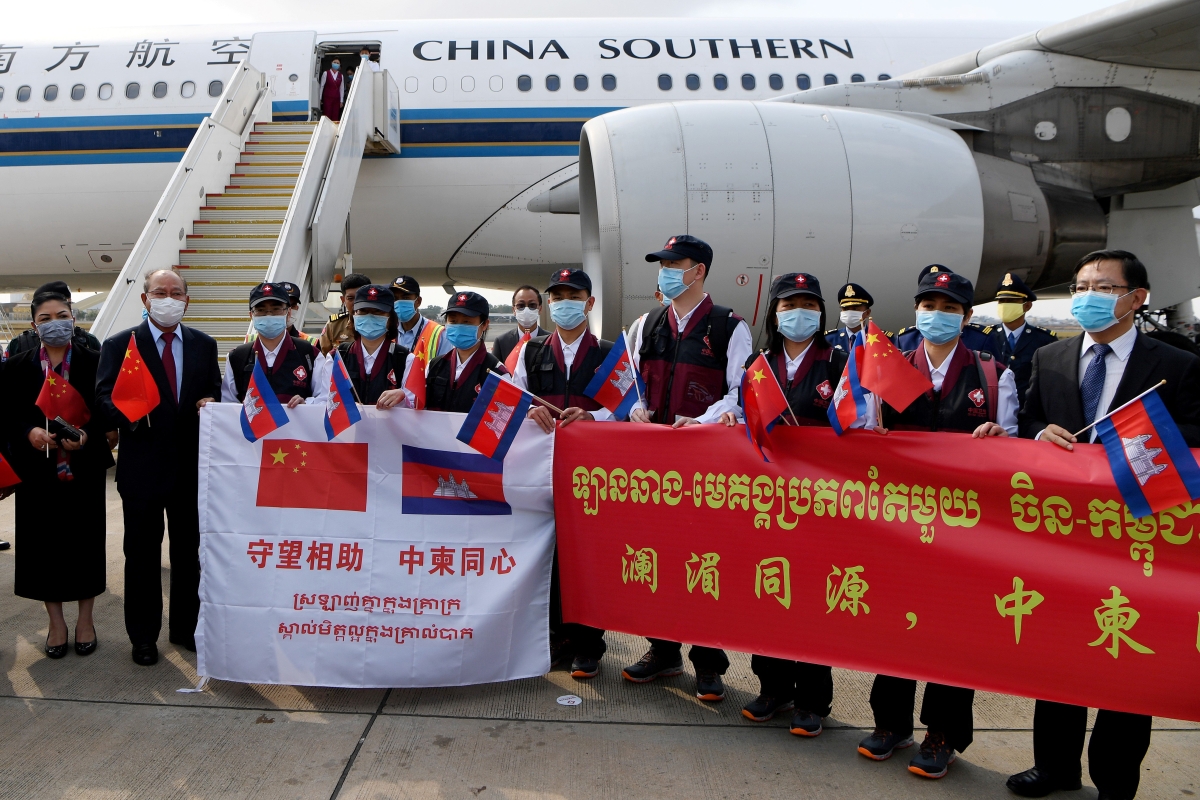

Chinese medical experts on the COVID-19 novel coronavirus arrived in Cambodia on March 23 to help local authorities deal with the virus. (TANG CHHIN SOTHY/AFP/Getty Images)

The following is the full text of a piece penned by Asia Society Policy Institute Senior Fellow Richard Maude on the Coronavirus and Southeast Asia.

In Southeast Asia, a region of some 655 million people, a humanitarian catastrophe looms as the COVID-19 pandemic advances and economies falter.

The number of confirmed cases across the region remains relatively small compared to the hardest-hit parts of the world. But these numbers are accelerating and the reported figures almost certainly represent only a fraction of the true number of infections.

Southeast Asia has all the ingredients for rapid spread of the virus – mostly weak public health systems, crowded cities, poverty, and significant migrant worker flows. Although now significantly reduced, tourism has been another vector.

In Jakarta, people are being filmed collapsing in the streets. By some estimates, Indonesia could have tens of thousands of cases within weeks.

The danger is clear and present. The World Health Organization has called on Southeast Asian governments to urgently implement more aggressive measures to stop the virus spreading.

The response has been mixed, a patchwork of measures covering international travel restrictions, social distancing measures, and partial shut-downs. Apart from Singapore, testing and tracing levels remain very low and in most countries face masks and other essential medical equipment are in short supply. Doctors are dying.

Indonesia has suspended visa free arrival and put entry restrictions on travelers from countries with high COVID-19 infection rates.

But President Joko Widodo has resisted calls for aggressive social distancing measures or lockdowns, reportedly out of concern over the economic impact, particularly on the millions of Indonesians who eke out a precarious existence in the informal sector of the economy.

Indonesia was hit hard by the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis. The violent riots and looting that followed led to the dramatic collapse of the Suharto regime, an event seared into national consciousness.

Even so, Widodo is being pressed to do more, faster by some of Indonesia’s regional governments and governors, anxious doctors and the media. Jakarta Governor Anies Baswedan has declared a “state of emergency”, seeking a soft lockdown of an immense city that is hard to govern at the best of times. Entertainment venues are being shut down and citizens encouraged to work from home where they can. This won’t be enough.

Elsewhere in the region, Vietnam, Malaysia, and the Philippines have shut their borders to travelers. Thailand has imposed strict restrictions on entry that effectively amount to a ban on flights and is implementing social distancing measures in Bangkok.

Some countries are moving more aggressively. Malaysia is using its military to enforce a partial 14-day shutdown of the nation. And in the Philippines, the police and defense forces are similarly engaged in a massive lockdown of Luzon Island and an estimated 60 million people.

Singapore has been cited for its “model” response to the coronavirus, implementing sophisticated testing, tracing and social distancing measures. But these have not prevented a recent surge in new infections. Many of these are Singaporeans or long-term residents returning home, but the government has now closed its borders to all short-term visitors.

Cambodia is a study in contrast – its strongman ruler Hun Sen has tied himself and his country closer to China than any other Southeast Asian nation. He visited Beijing to praise China’s efforts to contain the virus and recklessly declined to ban flights from China because, he said, it might strain relations between the two countries. Hun Sen has shown no such hesitation when banning travel from other countries with high COVID-19 infections.

The Economic Impact

Like the rest of the world, Southeast Asian economies have been hit hard by simultaneous supply and demand shocks.

China is the region’s number one trading partner and the largest source of inbound tourists. China is also a significant source of foreign investment, including in Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects.

China’s shut down in January and February slowed or stopped the supply of the raw materials on which many Southeast Asian manufacturers depend and significantly reduced demand for finished products.

Southeast Asian manufacturers of goods such as shoes, textiles, electronic products, and automobiles, for example, had to slow or stop production, laying off thousands of workers in the process. Exports have been stuck in Chinese ports.

Major infrastructure and other construction projects have also been affected by shortages of essential inputs and by the absence of Chinese workers, many of whom returned to China for the Lunar New Year and have been stuck there since. Large BRI projects are among those idling, as my Asia Society Policy Institute colleague Danny Russel reports here.

Southeast Asia’s tourism and hospitality industry, a source of significant national income (20 percent, for example, in Thailand and the Philippines) and jobs has taken a heavy hit from travel bans and restrictions.

These supply and demand shocks for Southeast Asia’s export-oriented industries will ease over time if China continues to recover and re-start its economy. But many businesses – small and large – will have gone under by that point.

The ability of Southeast Asia’s economy to bounce back will also depend on their own government’s efforts to contain the pandemic. A Chinese recovery could come just as regional governments are forced to take drastic steps to shut their societies down: a double hit for local businesses and the millions of Southeast Asians for whom life is a day-to-day proposition.

Finally, capital outflow from emerging markets worldwide has been significant since the crisis began, potentially affecting longer-term development prospects in Southeast Asia.

With so many variables at play, estimates of the overall economic impact of COVID-19 are largely guesswork at this stage. The Asian Development Bank has modeled hypothetical worst-case scenarios. In the case of Southeast Asia, the negative impact of COVID-19 ranges from just over half a percent of GDP for Brunei to nearly four percent for Cambodia.

In the medium term, manufacturers inevitably will look afresh at their supply chain dependencies. Singapore’s government has already said it won’t in the future let itself be reliant on just one supplier for essential goods.

Some manufacturing has drifted out of China into countries like Vietnam in recent years as a result of higher labor costs and the U.S.-China trade war. We are likely to see more of this. But China won’t suddenly stop being a major global manufacturing hub. Shifting production is expensive and China still has some significant advantages, including an immense and readily deployable labor force. And COVID-19 proves that no diversification strategy can survive a global pandemic.

The Virus and Geopolitics

The longer-term geopolitical consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic are hard to predict.

Southeast Asian economies have been hurt badly by their dependence on China for raw materials and as an export market. Frightened publics might blame the source of the pandemic for their suffering.

Equally, China is now helping Southeast Asian nations respond to the pandemic in very public ways. Beijing is providing technical advice on how to beat the pandemic and shipping large quantities of medical supplies to the region.

The first, but almost certainly not the last, team of Chinese medical personnel to be sent to Southeast Asia landed in Cambodia on 23 March. “Chinese experts to the rescue” was the welcoming banner from the Phnom Penh Post.

Such aid is sorely needed and should be welcomed, even as we recognize it will be used by China to build influence and advance its political, security and economic interests in Southeast Asia. Despite its long history as a generous supporter of global health security, U.S. assistance is not gaining the same traction.

More broadly, China has worked hard in Southeast Asia to limit what it calls “excessive measures” in response to the pandemic, such as travel bans, and to promote a positive narrative of its “resolute” and “highly responsible” efforts to fight the virus.

This has had only patchy success, as restrictions on travel from China in most Southeast Asian states show. Still, ASEAN foreign ministers were prepared to meet their Chinese counterpart, Wang Yi, in Laos in February at short notice for a show of solidarity, pledging to make the “utmost efforts to avoid disruptions to normal exchanges and cooperation”.

Outlook and Policy Responses

It is not surprising that in a region as diverse as Southeast Asia, governments are responding to COVID-19 in different ways. But public health systems will be quickly overrun and deaths from the virus will rise sharply if more aggressive containment measures are not put in place quickly.

The economic shock to the region from China’s shut down will be compounded if, as seems inevitable, many local businesses and industries are forced to close their doors to contain the virus. Millions of economically vulnerable Southeast Asians are at risk in the region’s gravest hour.

Southeast Asia’s partners need to be speaking up now, adding their voices to that of the World Health Organization and urging regional governments to move more quickly and more aggressively to contain the spread of the virus and strengthen front line medical responses.

Masks and other essential medical supplies are in short supply in many parts of the world. Wherever possible, Southeast Asia’s development partners must continue to work with regional countries and the World Health Organization to identify and respond to critical shortages. Expert advice on containment measures and support for public health bodies will continue to be valuable.

As the World Bank notes, local policy responses to cushion the economic impact of the virus will need to include tax incentives, subsidies and other support for small businesses, along with cash payments and stronger social safety nets for the most vulnerable. Interest rate cuts to drive exchange rates down will increase competitiveness. Ensuring sufficient liquidity in the financial system will be another challenge.

Regional countries are beginning to respond with stimulus packages and increased spending on front-line health care. But the cost will be huge and developing Southeast Asia needs assistance. Bilateral donors have a role to play, through development assistance and technical advice to central banks and economic ministries.

The World Bank, Asian Development Bank, and International Monetary Fund are also stepping up, putting in place emergency financing measures, debt relief, funding to strengthen health services and primary health care, and expanded trade finance.