China’s Economy Ahead of the Third Plenum: The End of the “China Miracle”?

China’s disappointing second-quarter economic numbers have triggered a widespread debate about the country’s economic future. GDP growth came in at a respectable 3.2% annualized growth rate. However, for some analysts, the property sector's lackluster private investment, faltering exports, and declining prices signaled that China’s economic model was running out of steam. Observers used terms such as “the end of China’s miracle,” “a lost decade,” “Japanification,” and “a balance sheet recession” to describe the country’s current predicament.1 By contrast, some domestic observers argued that the current economic situation is a necessary side effect of the country's transition to Chinese President Xi Jinping’s new development model, which would aim to drive growth through innovation and output in emerging sectors such as new energy vehicles.2 Others noted that China’s economy is doing much better than those of many Western countries, and saw a conspiracy in the negative reporting rather than problems in China’s economy.3 Some Chinese economists argued that the overall trend is negative and that the country needs to address it.4

August’s slightly better economic numbers may dampen the debate, but the question remains whether China can avoid the “regression to the mean” of 2-3% medium-term growth that Lant Pritchett and Lawrence Summers predicted almost a decade ago.5 This question is important for China as well as the rest of the world: After all, China now accounts for 18% of the global economy, and was projected to deliver more than one-third of global growth this year, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The issue is also key for economic policy makers. If China is facing a cyclical downturn, an economic stimulus would shore up growth; however, if the country is experiencing a structural slowdown, reforms may be necessary to revamp growth.

Economic Headwinds

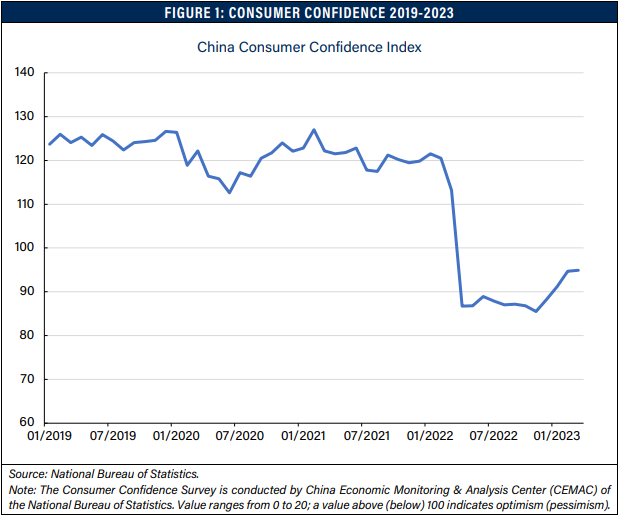

China’s economy has had a challenging exit from its zero-COVID policy. Whereas the first quarter of 2023 saw a sharp rebound of GDP growth (9% on an annualized basis), that number fell to 3.2% in the second quarter — still respectable in a global context, but less than many had expected. Though the government’s modest indicative growth target of “around” 5% for 2023 may still be met, private forecasters have downgraded their more optimistic predictions in recent months. The government increasingly worries about the consequences of the slowing economy, perhaps best represented by the rising unemployment rate for 16- to 24-year-olds, at a record 21.3% in June 2023. The government has since stopped publishing the number. Meanwhile, producer prices are falling, and real estate prices have weakened.

Short-term economic indicators in August were slightly better. Industrial production growth accelerated to 4.5% year-on-year (YOY) in August from 3.7% YOY in July; exports in renminbi (RMB) fell 3.2%, compared to a 9.2% decline in July; retail sales grew by 4.6%, compared to 2.5% in July; and the decline in property sales slowed to 12.2%, from 15.5% in July. Still, fixed asset investment weakened, growing by 1.8% in August compared to 2.5% in July. These data points, while encouraging, do not yet promise a recovery of growth to pre-COVID levels.

Many of China’s economic troubles have been induced by policy. China’s zero-COVID policy was initially successful, and the economy rebounded strongly in 2021, with 8% GDP growth. However, the highly infectious Omicron variant prompted a spike in lockdowns and increasingly restrictive measures on mobility. Accordingly, the economy slowed to a low of 2.2% growth in 2022. The sudden end to the zero-COVID policy in December 2022 initially boosted household consumption, particularly in services (such as domestic tourism); however, this growth petered out in the second quarter of 2023. The damage done to job creation has been large: In the years before the pandemic, the service sector created 10 million new jobs each year, absorbing a large number of college graduates, according to Xing Ziqiang of the China Finance 40 Forum, a Beijing-based think tank.6 During the pandemic, Xing said, the service sector created just over one million jobs per year.

A second brake on growth came from the property sector. That sector had been a major driver of investment demand since the 2008 global financial crisis; however, it had also accumulated debt and, in the eyes of authorities, become a source of risk to China’s financial stability. Xi Jinping frequently repeated the slogan, “housing is for living in, not for speculation,” which also appeared in many Party documents. To minimize risk, the authorities declared the so-called “three red line” policy in 2020, which effectively limited credit available to property developers. When advanced sales as substitute finance dried up during the COVID-19 pandemic, key developers ran into financial problems, triggering a sharp drop in property sales, new construction, and land transactions. In turn, this drop affected local government finances, which in recent years had increasingly relied on revenues from land sales. While stabilizing measures seem to have halted decline in this sector, the recovery remains wanting. Moreover, demographics and urbanization trends suggest that the property sector will likely slow the economy for several years to come.

Low confidence within the private sector generates a third headwind to growth. The recent clampdown on internet platforms, as well as the perception that the current administration favors state-led development, has made private entrepreneurs wary of new investments. Aside from the sharp contraction in investment in the property sector, diminishing growth prospects, and ample available production capacity amid sagging demand, have also reduced the need to invest in new capacity. As a result, private investments are shrinking, further slowing economic growth. Most of the decline is from a fall in property investment, however, and private investment in manufacturing is still growing.

Foreign investors face particular challenges in the new era. In addition to COVID-19 restrictions, they have to manage an environment dramatically changed by new cybersecurity and data security laws, amendments to anti-espionage laws, and the possible repercussions of great power competition. While total foreign direct investment (FDI) numbers held up in 2022, the first quarter of 2023 saw a sharp decline. Moreover, the nature of foreign direct investment (FDI) is changing. According to a study conducted by the Rhodium Group, investment has become concentrated in big firms, with a growing share coming from Hong Kong and Singapore, indicating that these funds are in fact Chinese firms repatriating offshore funds.7 The outlook of foreign investors has become increasingly subdued. Some have called it quits: When the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China conducted its 2023 Business Confidence Survey, 11% of respondents said they had moved investment out of China.8 A survey asking members of the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai about business prospects in China yielded the worst results since the organization started the survey in 1999.9

Efforts to stimulate the economy are constrained by high levels of debt, in particular of local governments and households. According to the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the total debt-to-GDP ratio reached close to 300% by the end of the third quarter of 2022, twice what it was before the global financial crisis. China’s debt-to-GDP ratio now exceeds that of most advanced economies and all emerging market economies. Of that debt, household debt-to-GDP stands at about 60%, which equals the household income share in GDP. Government debt is now some 75% of GDP; when including debt incurred by local government financing vehicles (LGFVs), that figure approaches 100%.

Debt of nonfinancial corporations increased more modestly in the past 15 years, especially when the numbers are adjusted to omit debt incurred by LGFVs, which is included in the statistics for corporations. The central government still has abundant capacity to take on additional debt, even though policies intended to support the economy through COVID-19 have eroded the tax base. Moreover, the central government has maintained its deficit at a conservative level of about 3%, conforming to now-discarded limits of the Eurozone.

A final headwind for China’s growth is the state of the global economy. China’s exports did very well during the COVID-19 pandemic, in part because the zero-COVID policy initially succeeded in keeping the economy open while most major economies were still struggling. Since last year, however, tightening monetary policies in other major economies have triggered a slowdown, which has in turn affected China’s exports. In June, the total value of exports was down by 8.3%, although the numbers are less dire in terms of volume.

Growing Policy Concerns

While authorities are concerned by slowing growth, they have not yet opted for an all-out stimulus. Rather, the July 2023 Politburo Meeting on economic work in the second half of the year reiterated a commitment to “proactive fiscal policy and prudent monetary policy,” a phrase already included in the December 2022 report of the Central Economic Work Conference (CEWC).10 The Politburo readout attributed the slowdown to “new difficulties and challenges, mainly due to insufficient domestic demand, difficulties in operating some enterprises, many hidden risks in key areas, and complex and severe external environment.” According to the Politburo, the solution lies in restoring confidence, promoting domestic demand, stimulating innovation, speeding up construction of a modern industrial system, increasing “high quality” growth, and focusing on emerging industries such as electric cars.

The sustained emphasis on “high-quality growth” signals that the authorities remain cautious about an all-out stimulus. “High quality” is shorthand for growth that the economy can achieve without additional policy stimulus, and is part of Xi Jinping’s “New Development Philosophy.” The concept recognizes that the relentless pursuit of growth in previous eras has created inefficiencies and wasteful investment; the concept has inspired measures such as the “three red line” policy in real estate, and heightened central government reluctance to stimulate the economy. But the readout also suggests that several efforts to revamp growth are in progress or forthcoming. They include measures to promote consumption, including the recent decision to extend the tax credit for electric vehicles; measures to address local government debt; and an acceleration in the issuance of local government bonds, which would increase availability of financing for infrastructure The private sector, however, will have to drive a true revival in growth.

Re-Engaging the Private Sector

In recent months, Chinese authorities have demonstrated renewed affection for the private sector in order to bolster confidence. Meeting with leading private sector representatives during the Two Sessions in March, Xi Jinping assured them of his “unwavering support” for the private sector. The “two unwavering” is Party language for support of both the public and private sectors, and was reiterated in a document jointly issued by the Central Committee of the Communist Party and the State Council in support of the private sector.11 Chinese Premier Li Qiang followed suit in July by meeting with technology entrepreneurs and pledging support for the “platform economy” previously weakened by the regulatory crackdown.12 The National Development and Reform Commission promised support to the private sector as well, and set up a department to implement new measures.13

The Central Committee/State Council document pledged to make the private economy “bigger, better and stronger,” with a series of policy measures designed to help private businesses and bolster the flagging post-pandemic economic recovery. At the same time, the document reaffirms the government’s measures against monopolies, non-market behavior, and corruption. It also promises plenty of guidance for the private sector (the word “guide” appears 22 times in the document), and refers to the “traffic light” system for private investment, which was first articulated during the technology crackdown to control the “excessive expansion of capital.”14

The Ministry of Finance extended the tax-relief program, initially scheduled to expire at the end of 2023, until 2027. Private companies will enjoy a simpler process to obtain research and development tax deductions and a shorter wait to receive export rebates. China’s central bank, the People’s Bank of China, pledged to steer more financial resources towards the private economy, including extending debt financing tools to firms that requested broader bond financing channels.15

Whether these measures and policy statement suffice to restore the confidence of the private sector remains to be seen. Without such confidence, a strong rebound in the economy is hard to imagine. Since the onset of “reform and opening” in 1978, the private sector has steadily become the mainstay of China’s economy. According to government sources, it now contributes about 50% of the country’s tax revenue, 60% of its GDP, 70% of its technological innovation, and 80% of its urban employment.16

Officially, China has recognized the importance of the private sector since former President Jiang Zemin articulated his “three represents” theory in 2000 and the government enshrined private property in the state constitution in 2004. Well before that, former Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leader Deng Xiaoping’s “cat theory” had given the blessing to the private sector after decades of focus on state planning. At the same time, the “basic economic system” considers the public sector to be dominant, so the private sector is acutely conscious of changes in political winds. Many such changes have occurred in recent years, including the crackdown on the technology sector and the potential implications of Xi Jinping’s “Common Prosperity” strategy and “New Development Philosophy.” More broadly, the political changes in Beijing — namely, the growing focus on national security, Xi Jinping’s consolidation of power, and the increasing dominance of Party over government — have created a less predictable environment for the private sector, despite the authorities’ stated objective of “rule by law.”

Boosting Consumption

A second plank in the government’s strategy to counter the ongoing slowdown is to increase domestic demand, particularly regarding consumption. In December 2022, the government issued a strategy for increasing domestic demand, though specific measures have yet to follow.17 Hardly new, this strategy has been integral part of the “dual circulation” approach intended to lessen China’s dependence on foreign demand. That objective dates back to the administration of former President Hu Jintao, when then-Premier Wen Jiabao cautioned that “the biggest problem with China's economy is that the growth is unstable, unbalanced, uncoordinated, and unsustainable.”

Since then, China’s household consumption has increased as a share of GDP, but only slowly. Rising from 35% in 2008 to 39% in 2018, that share fell back to 38% during the COVID-19 pandemic. This is not only of significance for China: Globally, China’s consumer market is far less important than its weight in world GDP suggests. Whereas China’s GDP now approximates three-fourths of that of the United States, its consumer spending is equal to only 40% of U.S. consumption. Nevertheless, China’s consumption has been growing at a respectable rate, outpacing GDP growth for most of the past 15 years. The question is: Can consumption save growth going forward? And if so, how?

There are two schools of thought as to why consumption is so low in China. One view, promulgated by economists Michael Pettis and Zhang Jun, among others, argues that China’s household share of national income is too low to make consumption a vehicle for growth.18 Others claim that Chinese households are saving too much for a variety of reasons, including a weak social safety net, high costs of education, and high down payments on property. This is not a trivial difference among academics: In order to implement effective policies for economic growth, leaders must interpret consumption patterns correctly.

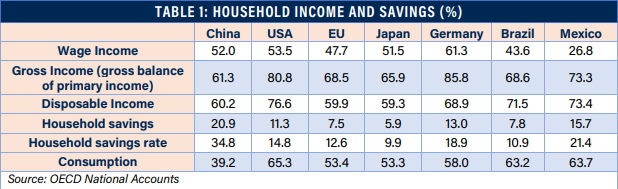

Compared to the United States, China’s disposable household income as a share of GDP is low — 60% in China compared to 77% in the United States, according to Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) data for 2019, the most recent available for China (Table 1).19 This share is not too different from that in the EU (also 60%) and Japan (59%). The main difference between China and the United States is that entrepreneurial income is much higher in the United States, due to friendly tax treatment. Another difference is that Chinese households receive hardly any dividends from enterprises (0.4% of GDP), less than 10% of what households in the EU and the United States receive. Finally, China’s statistical bureau underestimates imputed rents (the amount of implicit income an owner-occupier receives from not having to pay rent). This could add as many as four additional percentage points of GDP in disposable income — and, by definition, the same amount of consumption.

The substantial differences in consumption between China and other countries in the table above result from China’s high household savings rates. Chinese households put about 35% of their disposable income aside in savings, much more than households in the United States (15%), the EU (13%), and Japan (10%). This means that Chinese households save about 21% of GDP, compared to 11% in the United States, 8% in the EU, and 6% in once-frugal Japan.

In terms of policy, this disparity means that addressing the underlying causes of such high savings rates would have more, and more immediate, results than increasing the income share of Chinese households. Strengthening the country’s social safety net, shoring up the pension system, broadening unemployment insurance, and expanding health insurance would all reduce the incentives for Chinese households to save. Another useful measure would be a reduction in the down payments needed to buy real estate, though this might conflict with government policies for that sector.

Finally, China could gradually increase the household share in the economy. This will happen as wage increases outpace GDP growth, but policy could also drive such a shift. Notably, the paltry dividends that state-owned enterprises (SOEs) pay to the government could be increased, and in turn used to strengthen the social safety net.

None of this is out of line with the views espoused by China’s economic thinkers. Last November, Liu He, the previous vice premier and economic czar, wrote in the People’s Daily, the CCP newspaper, that “it is necessary to strengthen demand-side management, promote high-quality full employment, improve the distribution system, improve the social security system … fully release consumption and investment demand, and make the construction of a super-large-scale market a sustainable historical process.”20 However, the Party leadership seems more reluctant to embrace these ideas, as a stronger social safety net could risk “welfarism,” which Xi Jinping sees as one of the main problems affecting the West.21

A “Balance Sheet Recession”? Different Experiences in China and Japan

High debt, demographic headwinds, declining real estate prices, and signs of deflation have triggered a debate about whether China is experiencing a “balance sheet recession.”22 Richard Koo, then the chief economist for the Japanese investment bank Nomura, coined this term in the late 1990s to describe Japan’s situation after the collapse of the financial bubble formed earlier in the decade. Koo said that because of the massive decline in asset prices, households, the corporate sector, and banks all focused on repairing their balance sheets. As a consequence, demand plunged, and Japan entered a decade-long recession. To escape it, he argued, Japan should embark on massive public spending campaign. Today, according to Koo, China might be approaching a similar situation.

There are some similarities between 1990s Japan and present-day China. But a “balance sheet recession" for China still seems unlikely. The blow to Japan’s balance sheets at the time was staggering: The Nikkei Stock Index fell from 39,000 at its peak to 13,000 by the end of the decade. Commercial real estate lost 80% of its value, and residential land prices fell by two-thirds between 1991 and 2005, according to BIS data. At the time of the collapse, Japan was already an aging society, and the urbanization rate, at some 77% in 1990, had started slowing.

China is in a very different situation today. Though the property sector is seriously affected by the current downturn, its decline has manifested in the volume of sales and construction, not in actual price changes. At least for now, the perceived wealth of Chinese households, which hold about two-thirds of their wealth in real estate, has barely been affected.23 The balance sheets of the sector itself have been adjusting in both directions — the policy objective of deleveraging triggered the problems in the first place. According to the investment research firm Gavekal-Dragonomics, the balance sheet of the sector has shrunk by about RMB 1.7 trillion (about USD 230 billion, or 1.4% of GDP). On the other side of the balance sheet, this was matched by a decline in the sector’s equity of RMB 401 billion, and a reduction in debt of RMB 1.3 trillion, out of a total of some RMB 19 trillion in outstanding loans to developers.

Thus far, these changes represent a minor adjustment, not the major shock Japan experienced in the early 1990s, or even the decline in asset values the United States experienced during the 2008 global financial crisis. According to former Bank of Japan Governor Masaaki Shirakawa, the decline in the combined value of Japanese property and stocks during the country’s recession amounted to about 230% of GDP; in the United States, the decline in asset values after the global financial crisis equaled 100% of GDP.24 For now, the decline in Chinese property values is far smaller, and losses are mainly contained within the property sector itself. China’s corporate sector as a whole is far less leveraged than Japan’s in the 1980s: The debt-to-equity ratio is currently about 1.25 in China, and has reduced in recent years. In Japan, that ratio was three times higher during the peak of the bubble.

Koo is correct to flag that China’s economy has become less and less responsive to monetary policy. Indeed, the modest reductions in interest rates have barely had any effect. The reason is clear: Companies face uncertain growth prospects, have abundant capacity to meet current needs, and remain uncertain as to what the new policy environment means for them. Moreover, in line with government policy, they have already been deleveraging for a number of years. Households face uncertainty about future property prices and completion of any property they may buy. Furthermore, many people have seen their children, or the children of their neighbors, struggle to find jobs. These are not conducive conditions for major consumer spending growth.

Rather than a “balance sheet recession,” China’s economic plight can better be described as an “expectations recession.” The July 2023 Politburo meeting (and before that, the December 2022 CEWC) recognized as much, stating that: “To do a good job in economic work in the second half of the year, we must … focus on expanding domestic demand, boost confidence, and prevent risks.” In such circumstances, a fiscal stimulus could help temporarily, but lasting growth would require deeper reforms to change expectations held by households and the private sector.

Policies for the Remainder of 2023

After the release of the Central Committee/State Council document, a range of measures were announced to support the property market.25 The readout of the July 2023 Politburo meeting had suggested as much, as it called for policies to “better meet the rigid and improved housing needs of residents, and promote the stable and healthy development of the real estate market.” Such measures could include support for real estate developers to finish housing under construction, the relaxation of down payment requirements and mortgage restrictions on second homes, lower mortgage rates, and a rebate for the tax on property sales. These changes could lead to a stabilization of property prices, which in turn would help repair shaken consumer confidence. Regardless of the results, real estate will continue to slow economic growth for the foreseeable future, as demographics and market saturation point towards a much smaller sector going forward.

Meanwhile, the risk of default by real estate developers has hardly receded, as the recent troubles of Chinese developers like Country Garden demonstrate. The government will have to address the implications of the real estate bust for the financial sector. Certainly, more bad debts will accrue as the sector adjusts, and more developers may default. The government could continue to allow banks to carry bad debts as “investments” on the balance sheet, or they could use local asset management corporations to acquire the bad debts, financing these acquisitions with credits from the same banks. This “financialization” of bad debts is likely to be the mainstay of the solution. Such a strategy would force depositors to pay for the bad investments through lower returns on their deposits. Moreover, tax payers would suffer the lower contributions of banks to tax revenue.

As for the LGFV debts, the July 2023 Politburo meeting offers some hope as well: “We should effectively prevent and resolve local debt risks and formulate and implement a package of debt plans,” the readout states. The government may approach bad property debts similarly: Bank credits to LGFVs could be exchanged for local, government-backed bonds, which promise lower yield but more security. Ultimately, the central government is trying to avoid bailing local governments, which is one reason why the solution has taken time to emerge.

The July 2023 Politburo meeting did not promise any major stimulus, stating that: “We should continue to implement proactive fiscal policy and prudent monetary policy” has been the line for some time now, and it promises little in additional stimulus. Apart from extending existing tax reductions until 2027, as previously mentioned, and expediting local government borrowing that had already been agreed upon, the Ministry of Finance offered little in terms of extra stimulus. However, if growth deteriorates further as the year progresses, the possibility of a more forceful stimulus cannot be excluded.

The Opportunity for the Third Plenum

The Third Plenum of China’s 20th Central Committee, expected to take place in October 2023, is an opportunity to present a program of structural reforms that could address some of the country’s economic challenges. The Third Plenum is also the first opportunity for Xi Jinping’s new economic team to present an integrated vision of its vision for China’s economy. As such, a credible plan could remove some of the uncertainties that have affected investors and consumers alike.

Since the Third Plenum of the 11th Central Committee in 1978 unleashed Deng Xiaoping’s “reform and opening up,” Third Plenums have been used to spell out China’s economic reform agenda. The Third Plenum of the 14th Central Committee in 1993 introduced the “socialist market economy,” and the Third Plenum of the 18th Central Committee introduced a set of measures favoring productivity and innovation as factors for growth, including the designation of the market as the deciding factor in the allocation of resources. These reforms were only partially implemented, and the Third Plenum of the 19th Central Committee was used not for economic reforms, but for achieving consensus on the constitutional reforms that paved the way for Xi Jinping’s third presidential term. As a result, a decade has passed since the introduction of a comprehensive economic reform program.

Central Committee Plenums do not serve to settle major ideological issues; that role is reserved for National Party Congresses. The 20th Party Congress in October 2022 reaffirmed the primacy of economic development, a priority that was established in 1978 with “reform and opening up.” According to Xi Jinping’s work report to the Party Congress, the pursuit of economic development is a “central task” and a “top priority” of the Party, and the “New Development Philosophy” will drive policy during China's quest to achieve “a new development pattern, which is balanced, open, sustainable and equitable.”26

At the same time, Xi Jinping emphasized national security as the basis for economic development. Aside from more traditional security elements such as food and energy, national security is increasingly broad in focus and application, partially in response to perceived external threats and partially to increase the CCP’s control over society. The tension between economic development and national security will continue to be a factor in economic policymaking for the foreseeable future. The Third Plenum is an opportunity to see if and how policy makers will combine the goals of economic development and national security.

China must overcome several obstacles to achieve the CCP’s primary goal of economic development. Demographic headwinds have become a growing tax on growth. The projected decline in the labor force is expected to reduce growth between 0.7% and 0.8% per year. Labor must be used more efficiently as well: Currently, a quarter of China’s labor force is engaged in agriculture, as opposed to about 3% in OECD countries. China’s household registration system and land user rights constrain the reallocation of labor toward more productive uses.

Aging could also reduce China’s high household savings, which in turn would lower investments, the main driver of growth since the global financial crisis. Investment efficiency must improve, as returns on investment have declined over the past decade. China’s incremental capital output ratio, a measure of investment efficiency, has rapidly increased, from 3.3 RMB investment for every one RMB increase in GDP in 2007, to 7.4 RMB investment for every one RMB increase in GDP in 2020. Accordingly, returns on assets have declined: Private sector returns decreased from 9.3% in 2017 to 3.9% in 2022, whereas SOE returns declined from 4.3% to 2.8% over the same period.

Meanwhile, growth in the total factors of production (TFP), a measure of the overall productivity with which the economy uses labor and capital, has slowed as well. Between 1980 and 2000, TFP growth contributed about 3 percentage points to GDP growth, or about one-third of total growth. However, in the past decade, this contribution has declined to 1 percentage point, or less than one-sixth of total growth.

The international environment has become less conducive to China’s growth. Xi Jinping’s report to the 20th Party Congress abandoned the idea of China being in an “important period of strategic opportunity,” and instead characterized the present as a “period of development in which strategic opportunities, risks and challenges exist at the same time.” Economic decoupling, though not yet apparent in the trade data, is increasingly a threat to China’s development, while U.S. restrictions on high-end semiconductors could derail a significant part of China’s technology agenda.

Furthermore, this international environment may mean that exports can no longer be the demand of last resort they have been in the past. China admitted as much in its 2016 “dual circulation” strategy. Tariffs introduced by former U.S. President Donald Trump's administration have already considerably reduced China’s exports to the United States; EU President Ursula von der Leyen recently announced an investigation into China’s decision to flood the EU market with electric vehicles, which could result in tariffs and a major slowdown in the growth of those exports.27

A Reform Package for the Third Plenum

The IMF now estimates that, without major reforms, China’s economic growth will fall below 4% in the coming years. At such levels of growth, China will not meet its objective of doubling its 2020 GDP by 2035, the end of the first phase of Xi Jinping’s “New Era.” To avoid this outcome, major reforms would need to meet several objectives. First, the reforms must increase productivity growth in China’s economy. Second, they must strengthen domestic demand. Third, they must sharpen China’s tools for macroeconomic management, now that the country can no longer rely on real estate and infrastructure to perform this function. Some key reforms that could fulfill these objectives are:

- Fiscal Reforms: At the core of the misallocation of capital in infrastructure and real estate are problems with the fiscal system. A growing demand for public services at the local level has not been met with more resources. Moreover, incentives for local government officials remain biased towards growth. Major fiscal reforms are needed, including expansion of the tax base, a better revenue base for local governments, and a reconsideration of the economic functions of local government and the intergovernmental fiscal system. A carbon tax, a property tax, and a broader application of the personal income tax are concrete options that would restore China’s revenue base over time.

- Financial sector reforms: China’s abundance of savings is likely to decline in the coming decades, especially in the absence of reforms to improve productivity. This means that the allocation of those savings would need to improve to keep growth at acceptable levels. Financial sector reforms are key to this, and the reorganization of the financial sector supervisor is a start. In the short term, it is critical to clean up LGFV debts, but deeper reforms are necessary to diversify the financial sector and increase returns on investment.

- Retirement age and pension reforms: The decline in the labor force, which has been ongoing for a decade, could be slowed by implementing reforms on the retirement age. If China adopted Japan’s retirement system, between 40 and 50 million additional workers would be in the labor force by 2035. Pension reforms could encourage people to work longer; simultaneously, they could improve the financial sustainability of the pension system and the expansion of that system for migrants and residents of rural areas (the urban and rural resident system).

- Household registration reforms: Urbanization has been a major driver of growth in the past, but has slowed in recent years. Urban dwellers now constitute about 65% of the population, but migrant workers account for almost 20% of this group. Moreover, about 25% of the labor force is still employed in agriculture, compared to an average of 3% among OECD countries. Additional reforms in the household registration system are therefore critical for increased mobility and labor productivity growth.

- Social safety net reforms: Providing rural citizens and migrant laborers with the same social protections enjoyed by urban workers would boost consumer confidence and consumption growth, as well as strengthening counter-cyclical policies and weaning the government off its reliance on infrastructure investment to stabilize the economy.

- State enterprise reforms: Even though China will continue to maintain a large SOE sector, there is broad agreement among policy makers that the sector should perform better. The Third Plenum of the 18th Central Committee in 2013 had already decided that better “state capital management” should be a priority. Increasing dividend payments from SOEs would be a good start. Divesting non-core activities, such as real estate development and tourism, from SOEs would allow the sector to perform better on its core tasks. Categorizing SOEs as non-commercial and commercial, and managing the latter through state investment companies, would further increase the returns that the state (and the Chinese people) would receive from their properties.

None of these reforms would be easy, and each one would negatively impact the interests of various groups, some of which have managed to block serious reform. Despite this opposition, a comprehensive and coordinated package of reforms will be critical for China’s future growth and development. The Third Plenum will therefore be the first serious test for China’s new economic team.

End Notes

- Adam Posen, “The End of the Chinese Miracle," Foreign Affairs, September/October 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/end-china-economic-miracle-beijing… “Does China Face a Lost Decade?” The Economist, September 10, 2023. https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2023/09/10/does-china-f…; Robin Wigglesworth, “China’s Japanification,” Financial Times, August 18, 2023; “China Is Likely to Face a ‘Balance Sheet Recession,’ Economist Says.” CNBC International TV, June 7, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HTabysmCpDo.

- Yao Yang, “Riding on New Cycle of Tech Innovation, China’s Economy is Entering a ‘Golden Age,’” Global Times, March 29, 2023, https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202303/1288183.shtml.

- John Ross, "The News is Full of Headlines About ‘China’s Economic Collapse’—Ignore Them," Morning Star Online, https://morningstaronline.co.uk/article/f/the-news-is-full-of-headlines….

- Wang Wen, “Rekindling the Passion for China’s Rise” (王文:重燃中国崛起的激情), Aixiang, August 27, 2023, https://www.aisixiang.com/data/145695.html.

- Lance Pritchett and Lawrence Summers, “Asiaphoria Meets Regression to the Mean,” National Bureau of Economic Research, October 2014, https://www.nber.org/papers/w20573.

- Xing Ziqiang, “Stronger Policies are Needed to Bolster Recovery," China Finance 40 Forum, May 22, 2023, http://www.cf40.com/en/news_detail/13332.html.

- Agatha Kratz, Noah Barkin, and Lauren Dudley, “The Chosen Few: A Fresh Look at Europe’s FDI in China,” Rhodium Group, September 2022, https://rhg.com/research/the-chosen-few/.

- European Chamber of Commerce in China, “Business Confidence Survey 2023,” https://www.europeanchamber.com.cn/en/publications-business-confidence-….

- “Western Firms in China Are Historically Glum About Outlook,” Bloomberg News, September 19, 2023, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-09-19/us-companies-are-the….

- 新华社记者 . “中共中央政治局召开会议 分析研究当前经济形势和经济工作 中共中央总书记习近平主持会议.” Weixin Official Accounts Platform. Accessed September 29, 2023. http://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MzA3NzMyMjUxMw==&mid=2652956177&idx=1&s….

- “Opinions of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council on Promoting the Development and Growth of the Private Economy” (民营经济是推进中国式现代化的生力军,是高质量发展的重要基础,是推动我国全面建成社会主义现代化强国、实现第二个百年奋斗目标的重要力量。为促进民营经济发展壮大,现提出如下意见), Xinhua, July 17 2023, https://www.news.cn/politics/2023-07/19/c_1129758014.htm,

- “Chinese Premier Meets Major Tech Companies, Vows More Support,” The Straits Times, July 13, 2023, https://www.straitstimes.com/business/china-premier-meets-major-tech-co….

- State Council of the People’s Republic of China, “Private firms on tap for more govt assistance,” news release, July 21, 2023, https://english.www.gov.cn/policies/policywatch/202307/21/content_WS64b….

- Interpret: China. “Disorderly Expansion of Capital: Performance, Risks, Root Causes, and Responses.” Accessed September 29, 2023. https://interpret.csis.org/translations/disorderly-expansion-of-capital….

- “China’s Private-Sector Crisis: Everything You Need to Know About the Mess and What Beijing is Doing to Clean it up,” South China Morning Post, August 13, 2023, https://www.scmp.com/economy/china-economy/article/3230781/chinas-priva…, accessed September 18, 2023.

- “China's Private Entrepreneurs Confident in Achieving High-Quality Development,”, Xinhua, May 23, 2023, https://english.news.cn/20230506/e287015d961946a187726cf60e3a056c/c.htm….

- “The Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council Issued the ‘Strategic Planning Outline for Expanding Domestic Demand (2022-2035)’” (中共中央 國務院印發《擴大內需戰略規劃綱要(2022-2035年》), Xinhua, December 14, 2022. http://big5.www.gov.cn/gate/big5/www.gov.cn/zhengce/2022-12/14/content_….

- Michael Pettis, "China Must Slow Down Investment if it Wants to Rebalance its Debt-Laden Economy,” South China Morning Post, September 12, 2023, https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3233610/china-must-slow-do….

- Zhang Jun: Chinese families have long faced the problem of low wages, and wages are not linked to nominal GDP growth (中国家庭长期面临低工资问题,工资与GDP名义增长不挂钩)NetEase Finance Think Tank June 23, 2023, https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/YtwmtMC_DB6Af5Mu80ygyQ, accessed 19 September, 2023.

- OECD.Stat, accessed July 30, 2023, https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?lang=en.

- Liu He, “Organically combine the implementation of the strategy of expanding domestic demand with the deepening of supply-side structural reforms” (把实施扩大内需战略同深化供给侧结构性改革有机结合起来), People’s Daily, November 4, 2022, http://paper.people.com.cn/rmrb/html/2022-11/04/nw.D110000renmrb_202211….

- Linling Wei and Stella Yifan Xie, “Communist Party Priorities Complicate Plans to Revive China’s Economy,” Wall Street Journal, August 27, 2023.

- William H. Overholt et al., “Could China Become Like Japan in the Early 1990s?” The International Economy, http://www.international-economy.com/TIE_W23_ChinaLikeJapanSymp.pdf

- “中国家庭财富调查报告:房产占比居高不下_中国经济网国家经济门户.” Accessed September 29, 2023. http://www.ce.cn/cysc/fdc/fc/201910/30/t20191030_33470849.shtml.

- Masaaki Shirakawa, “China Can Avoid 'Japanification' With Prompt Action,” Nikkei Asia, August 25, 2023, https://asia.nikkei.com/Opinion/China-can-avoid-Japanification-with-pro….

- “Real Estate Adjustment and Optimization Policies are Released Intensively” (房地产调整优化政策密集发布), Economic Information Daily, August 28, 2023, http://www.jjckb.cn/2023-08/28/c_1310738585.htm?utm_source=substack&utm….

- “Full Text of the Report to the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China,” China Daily, October 22, 2022, https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202210/25/WS6357e484a310fd2b29e7e7de.ht….

- “EU to launch anti-subsidy probe into Chinese electric vehicles,” Financial Times, September 13, 2023.