Balancing Act: Assessing China’s Growing Economic Influence in ASEAN

Executive Summary

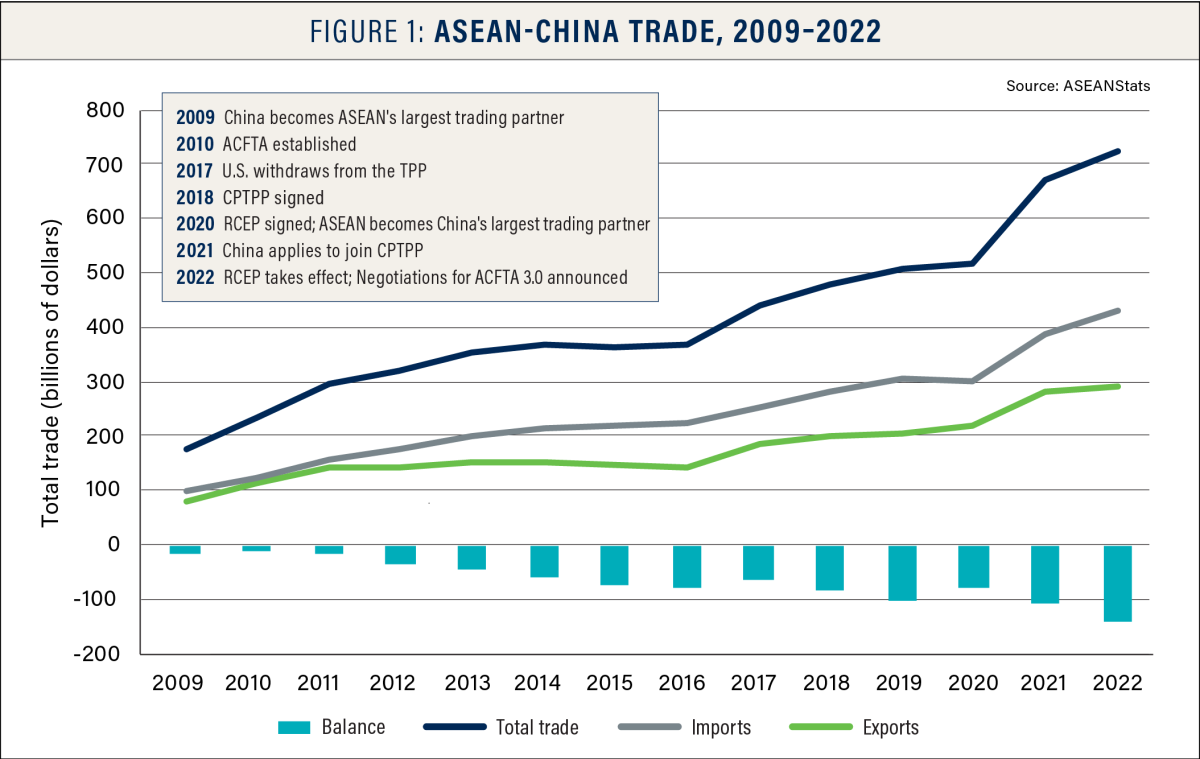

The 10 nations of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) face critical decisions in managing their economic ties with China — a vital economic partner yet a source of growing dependence and vulnerability. Over the past decade, ASEAN's trade in goods with China more than doubled, reaching $722 billion in 2022 and accounting for nearly one-fifth of ASEAN's global trade. Since 2020, ASEAN and China have been each other’s largest trading partner. Additionally, China's investments in ASEAN surged in 2022 to $15.4 billion, up markedly from the $9 billion invested in 2019 prior to the pandemic.

Landmark agreements like the ASEAN-China Free Trade Agreement (ACFTA) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) have accelerated trade growth through tariff cuts and closer supply chain links. ASEAN increasingly depends on China for manufactured inputs while exporting natural resources, some electronic goods, and agricultural products. This raises risks of supply chain disruptions, economic coercion, and impacts from China's economic fluctuations. As ASEAN weighs maximizing economic ties against managing strategic vulnerabilities, a nuanced balancing act is required.

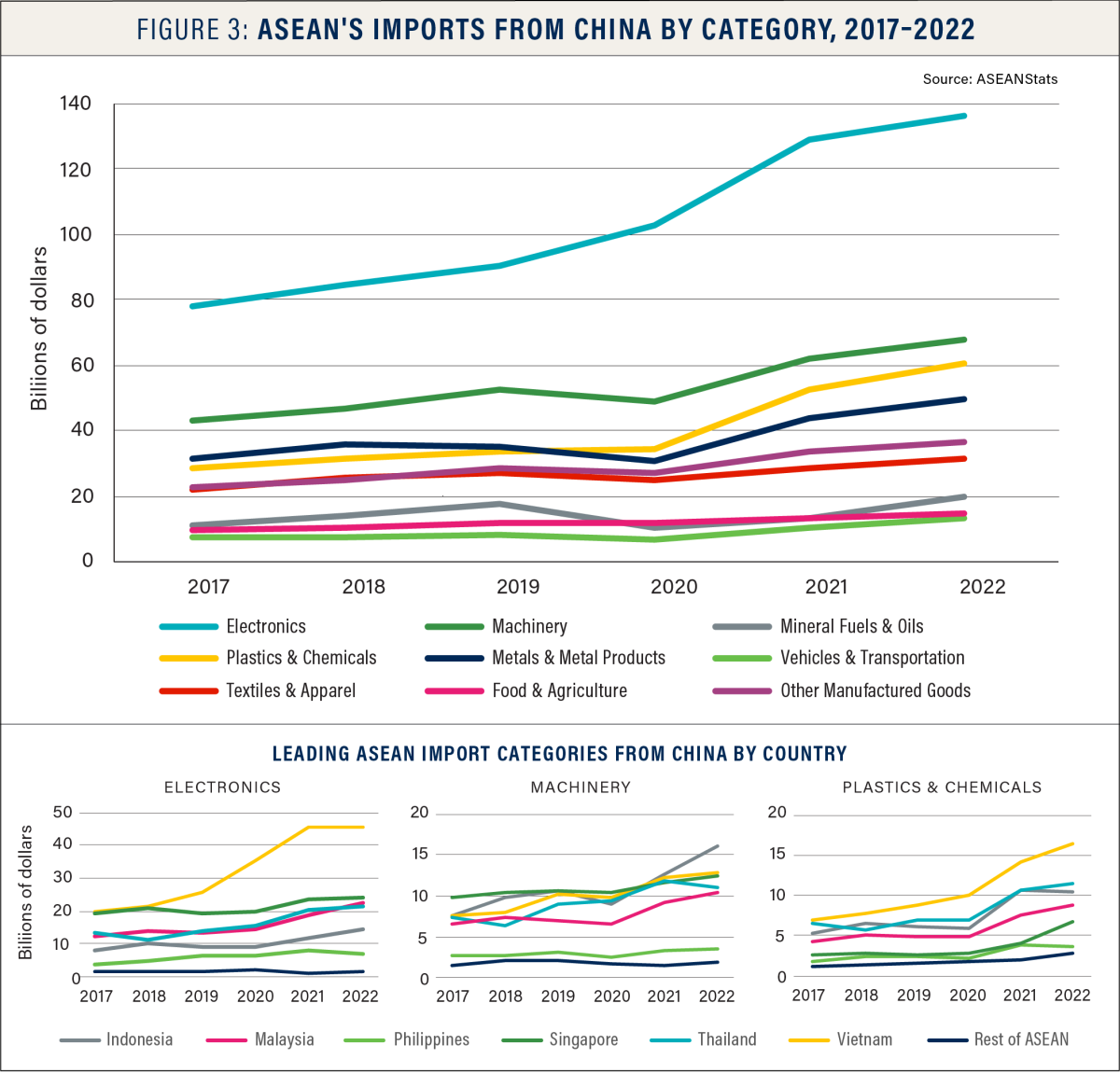

ASEAN imports far more from China than it exports, creating a trade imbalance that has deepened to nearly 4% of ASEAN's overall GDP in recent years. China is ASEAN's largest and fastest-growing source of imports. From 2017 to 2022, ASEAN's imports from China rose by 70% to reach $432 billion, with more than 80% of these imports comprising electronics, machinery, chemicals, plastics, aluminum, and other industrial goods. As ASEAN's largest supplier, China feeds the region's demand for inputs across the manufacturing, construction, and tech sectors.

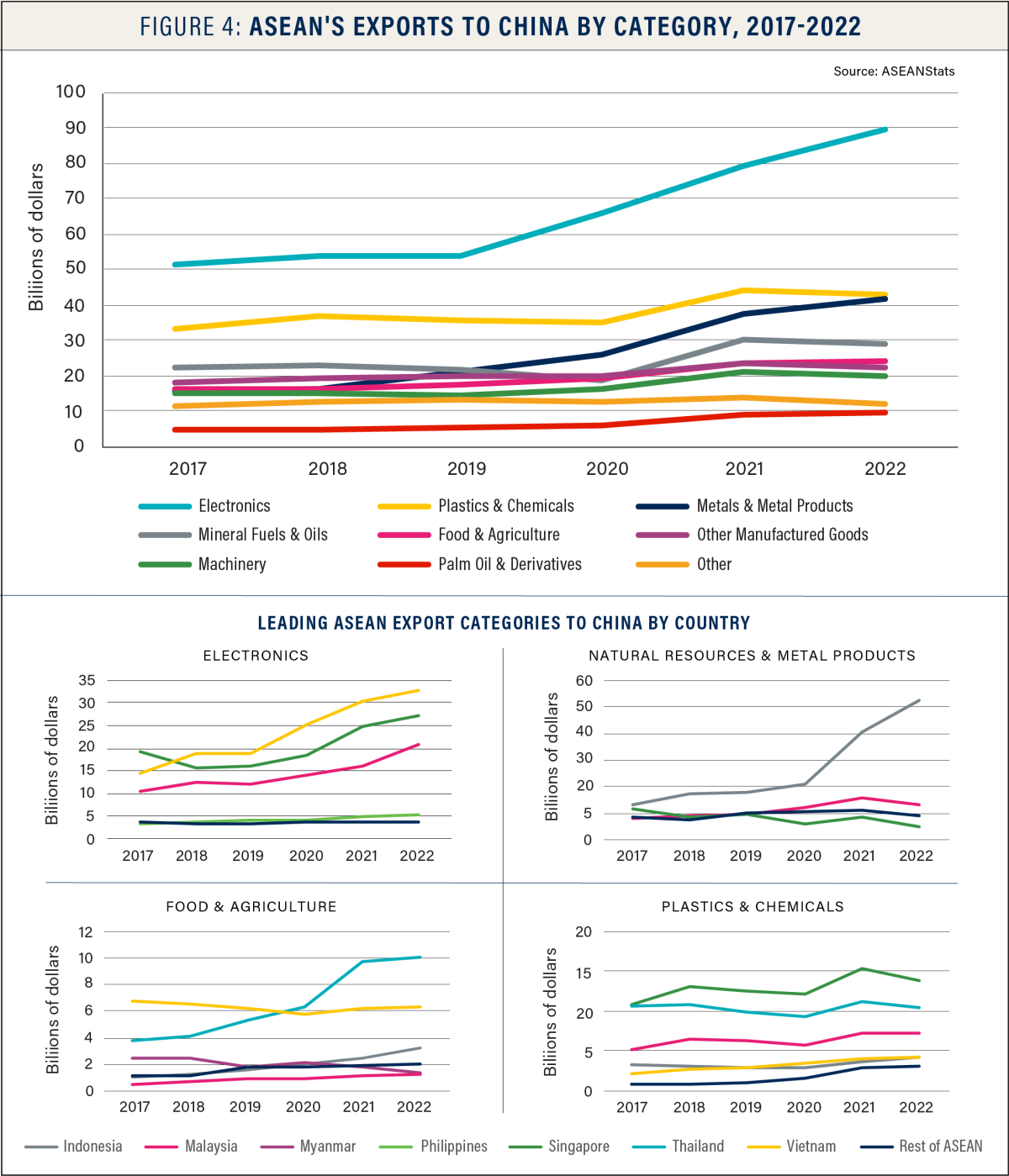

Over this same time period, ASEAN’s exports to China rose by more than 55%, with more than half the increase from exports of electronic equipment and metals such as ferronickel and stainless steel. Electronics exports alone, driven by pandemic demand, have surged 60% since 2019 to nearly $90 billion. Coal, plastics, and rubber were also significant contributors to this growth along with certain agricultural products such as palm oil and fruits. However, more modest growth in the export of plastics, chemicals, machinery, and manufactured goods highlights risks from China's strategic shift toward domestic production to supply components and raw materials.

China’s recent economic slowdown has highlighted the risks, with the ASEAN-China goods trade shrinking by nearly 10% in the second quarter of 2023 relative to the previous year. Given China's critical role as ASEAN's largest trade partner, this deceleration is having tangible economic impacts across ASEAN economies deeply connected with China.

As ASEAN navigates this complex economic landscape, pursuing a multipronged approach can build resilience. This involves diversifying trading partners to reduce reliance on any single economy, notably China, while strengthening intra-ASEAN trade and supply chain integration. Expanding trade partnerships through targeted diversification efforts and the pursuit of new and enhanced free trade agreements (FTAs) can help ensure a broader, more balanced trade network that insulates the region from external shocks and promotes sustainable growth.

Renewed U.S. regional economic leadership is critical to support ASEAN’s diversification efforts and provide an alternative to greater alignment with China. ASEAN must prioritize resilience, integration, and balance in trading ties to push back against excessive reliance on China. With strengthened cohesion and pragmatic policies, ASEAN can not only leverage the opportunities presented by Chinese trade but also mitigate risks of over-dependence. By pursuing this approach, ASEAN can increase its strategic flexibility and set the stage for a more resilient and sustainable economic future, even amid shifting dynamics involving major partners.

Introduction

The 10 nations of ASEAN — Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam — are an emerging global epicenter of economic dynamism and innovation. Their growing trade and investment ties with China promise great opportunities but also bring profound risks. China’s large markets and proximity offer ASEAN substantial benefits as a source of investment and an export market, from reductions in production costs through supply chain integration. Nevertheless, without diversification to safeguard their economies, excessive dependence on one major partner could leave ASEAN vulnerable. This concern comes into sharper focus amid escalating U.S.-China tensions.

Over the past decade, ASEAN's significant trade relationship with China has intensified. ASEAN's trade in goods with China more than doubled, reaching $722 billion in 2022 and accounting for nearly one-fifth of ASEAN's global trade.i China's investment flows into ASEAN also saw a substantial rise, reaching $15.4 billion in 2022. This growth underscores China's expanding regional influence. ASEAN and China now stand as each other’s largest trading partner.

Trade agreements, such as the ASEAN-China Free Trade Area (ACFTA) in 2010 and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) in 2022, have facilitated growth in the relationship by encouraging economic integration and supply chain connectivity. China continues to be aggressive in shaping regional trade rules through its pursuit of expanded provisions in the ACFTA, including rules on digital trade and supply chains, as well as its bid to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). Beijing’s financing of infrastructure projects in ASEAN through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and other investments expanded connectivity to facilitate trade.

Trade flows now weave a dense network of connections binding ASEAN to the Chinese economy. This intricate relationship poses risks. Beijing, driven by geopolitical objectives, might exploit its leverage as the key source of certain inputs crucial to ASEAN or as the main market for some ASEAN exports. Indeed, China has already demonstrated a willingness to assert its economic heft for geopolitical aims in ASEAN and beyond. Overreliance also leaves ASEAN vulnerable to China's economic fluctuations and potential supply chain disruptions. ASEAN and its member states should prioritize diversification and resilience as the surest way to mitigate these risks.

Since the U.S. withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in 2017, it has disengaged from championing new trade deals in the Indo-Pacific, leading to diminished economic influence in the region. While U.S. investments and trade flows with Southeast Asia have grown, the United States finds itself on the outside looking in on Asia's shifting economic dynamics. Renewed U.S. regional economic engagement would offer ASEAN a compelling alternative to greater alignment with China and encourage diversification. If the United States instead remains on the sidelines, emerging trade alliances will shape Asia’s economic architecture without its input. As Asian countries move ahead, the United States must forge deeper, enduring regional ties. Overdependence on Beijing is an outcome both ASEAN countries and the United States should seek to avoid.

Rising ASEAN: An Emerging Economic Powerhouse

ASEAN was established in 1967 by Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand during a period marked by intense conflict and internal disputes in Southeast Asia. The organization has expanded to include 10 diverse yet interconnected nations, each with unique cultures and differing levels of economic development. Home to 674 million people and boasting a combined GDP of $3.7 trillion, ASEAN represents the world's fifth-largest economy, a testament to its remarkable growth story.ii

Initially focused on regional security, ASEAN member states soon recognized that regional economic cooperation would reduce political tensions and foster long-term stability. In the post–World War II period, these nations concentrated on building and nurturing their domestic industries and reducing reliance on imported goods. This led to a transformative shift from predominantly agriculture-based to more industry-oriented economies, spurring growth and attracting significant foreign investment. Many Japanese companies began moving some manufacturing and assembly operations to ASEAN to benefit from lower production costs.

ASEAN's shift toward manufacturing and exports has been driven by targeted development in key industries. Singapore, Malaysia, and the Philippines are major exporters of semiconductors and high-tech electronics. Vietnam excels in exporting mobile phones and components, textiles, and footwear, whereas Cambodia mainly exports apparel and footwear. Thailand is a significant exporter of vehicles and auto parts as well as computers and other electronics. Indonesia leverages its abundant natural resources by exporting substantial quantities of palm oil, coal, nickel products, and other commodities. Malaysia leverages its resource wealth as a major exporter of oil and gas.

Today, with its remarkable trajectory projected to continue at an annual growth rate of 4.8% over the next five years,iii ASEAN stands as a major economic hub, bolstered by its trade, manufacturing, and vast consumer market. Its economic reach, spanning sectors from agriculture and mining to technology services and semiconductors, is central to Asian economic integration. Its strong links to production networks in China, Japan, and Korea, further reinforced by an extensive network of free trade agreements, are pivotal to Asia's dynamic economic landscape.

With total trade amounting to $3.83 trillion in 2022, ASEAN is now the world's fourth-largest trader, surpassed only by the European Union, China, and the United States.iv ASEAN is projected to experience the fastest trade growth globally,v a trend that will open significant opportunities and reflects ASEAN's rising prominence in the global economy. Boston Consulting Group forecasts that by 2031, ASEAN's exports will surge by nearly 90% to approximately $3.2 trillion annually, in contrast to the less than 30% growth forecast for overall global trade.vi

The Expansion of China’s Trade and Investment Relationship with ASEAN

Trade Momentum Accelerating between ASEAN and China

The ASEAN-China economic relationship gained momentum in the 2000s as China displaced Japan as the largest supplier of inputs for ASEAN exports. China’s 2001 entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) helped solidify its position as a global manufacturing powerhouse, attracting foreign investments and making Chinese products more competitive globally. For ASEAN countries, this presented an opportunity to supply components and raw materials to China's factories while gaining access to its consumer market. However, it also meant facing stiffer competition from less expensive Chinese finished goods in export markets and for foreign investments increasingly drawn to China. The relationship has been strengthened by the creation of the ACFTA in 2010 with its lowered tariffs and the signing of the RCEP in 2020, which harmonizes rules of origin and other regulations across the region. These landmark agreements fostered more deeply integrated supply chains between China and ASEAN, especially in such sectors as electronics and textiles. For a more detailed exploration of ACFTA's evolution and its transition towards ACFTA 3.0, see Box 1.

China emerged as ASEAN's largest trading partner in 2009, and trade between the two economies more than quadrupled by 2022. China’s trade with ASEAN countries has also seen a corresponding rise. ASEAN became its largest trading partner in 2020, accounting for 11.4% of China’s total trade volume in 2022. The list of sectors and products traded is diverse and includes electronics, machinery, petroleum products, steel, plastics, and chemicals.

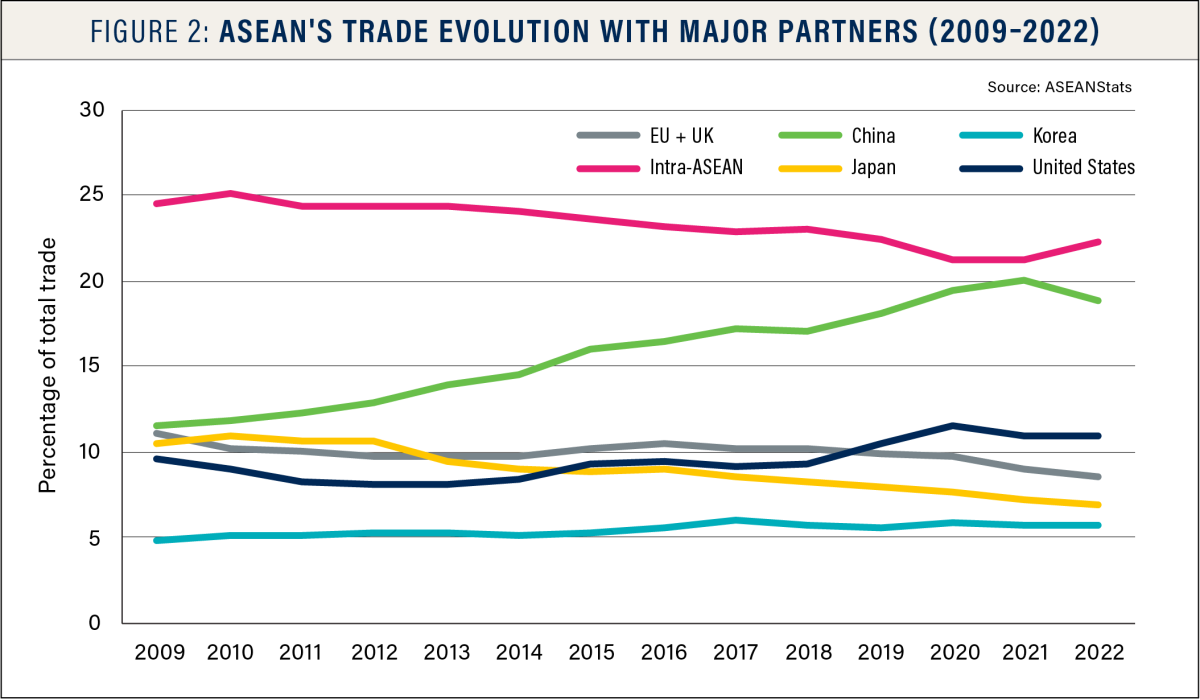

Over the past decade, ASEAN’s trade with Japan and the EU and between ASEAN member states has shrunk as trading with China and the United States has increased. Trade with China grew from 13% to 19% of ASEAN’s global trade. The U.S. trade share with ASEAN has grown from 8% to 11%, primarily driven by increased trade with Vietnam, followed by Singapore, Thailand, and Malaysia. ASEAN exported just over $290 billion to the United States — and China in 2022 but imported far more from China. Taiwan and since the pandemic India and Australia also reported growth in their respective trade shares with ASEAN.

ASEAN's Import Dynamics With China

China is ASEAN's largest and fastest-growing source of imports. Between 2017 and 2022, ASEAN imports from China increased by 70%, reaching $432 billion. This accounts for nearly 23% of ASEAN's total imports, a significant increase from the 16% share China held a decade earlier.

Electronics and machinery imports account for almost half of the 70% increase in the value of imports from China. Chemicals for various sectors, including pharmaceuticals and agriculture, as well as aluminum for construction and manufacturing, also play an important role. Industrial goods such as processed petroleum, steel, fabrics, and plastics also represent a significant share of imports. Indeed, more than 80% of imports from China are industrial goods — the components, materials, and capital equipment needed for domestic production and export expansion.vii This high level of sourcing concentration makes ASEAN especially vulnerable to potential supply chain disruptions. For example, shortages of machinery parts halted production at some Vietnamese manufacturing facilities during the 2022 COVID-19 lockdowns in China. Such dependence also hands bargaining leverage to China, given its control over supply and the pricing of key inputs on which ASEAN manufacturers rely.

China has solidified its role as ASEAN's primary supplier to meet rising demand across the manufacturing, construction, and technology sectors, but an analysis of specific sectors provides a clearer picture of these trade dynamics. ASEAN has grown increasingly reliant on Chinese inputs for its electronics industry in the past five years. Vietnam’s imports have more than doubled to more than $45 billion, largely driven by mobile phone components and semiconductors to produce finished electronics goods. Singapore saw a rise to $24 billion (up 25%), while Malaysia’s and Thailand's imports grew quickly to $24 billion (up 80%) and $22 billion (up 65%), respectively.

Key machinery imports include items that support the electronics industry, such as IT peripherals, networking hardware, and semiconductor fabrication equipment. Indonesia's imports from China more than doubled to $16 billion by 2022, driven by construction and manufacturing needs. Both Vietnam and Malaysia showed notable surges, with Vietnam's imports increasing from $7.5 billion to $12 billion. Malaysia followed a similar trend, largely due to computer and industrial machinery. Thailand increased its purchases to $11 billion, including sizeable increases for air conditioning systems, refrigeration equipment, and construction machinery.

Imports of plastics and chemicals are another key segment where ASEAN nations have markedly increased their imports from China, with Vietnam, Thailand, and Indonesia at the forefront. Vietnam's plastics imports jumped from $2.9 billion in 2017 to more than $7 billion in 2022, while Indonesia and the Philippines doubled their imports to meet rising demand for consumer goods and packaging. This surge includes organic chemicals, fertilizers, and rubber products, essential for diverse industries from agriculture to pharmaceuticals. Singapore's organic chemical imports, utilized in petrochemicals, pharmaceuticals, soaps, and dyes, surged by more than 550% to $4.2 billion. Malaysia experienced a sharp uptick in its chemical imports for electronics and battery production.

Demand for pharmaceutical and medical imports spiked in Southeast Asia in response to COVID-19, and ASEAN countries procured 480 million Chinese vaccine doses by the end of 2021. Indonesia made more than half of these acquisitions, but the Philippines and Thailand also made significant vaccine purchases.

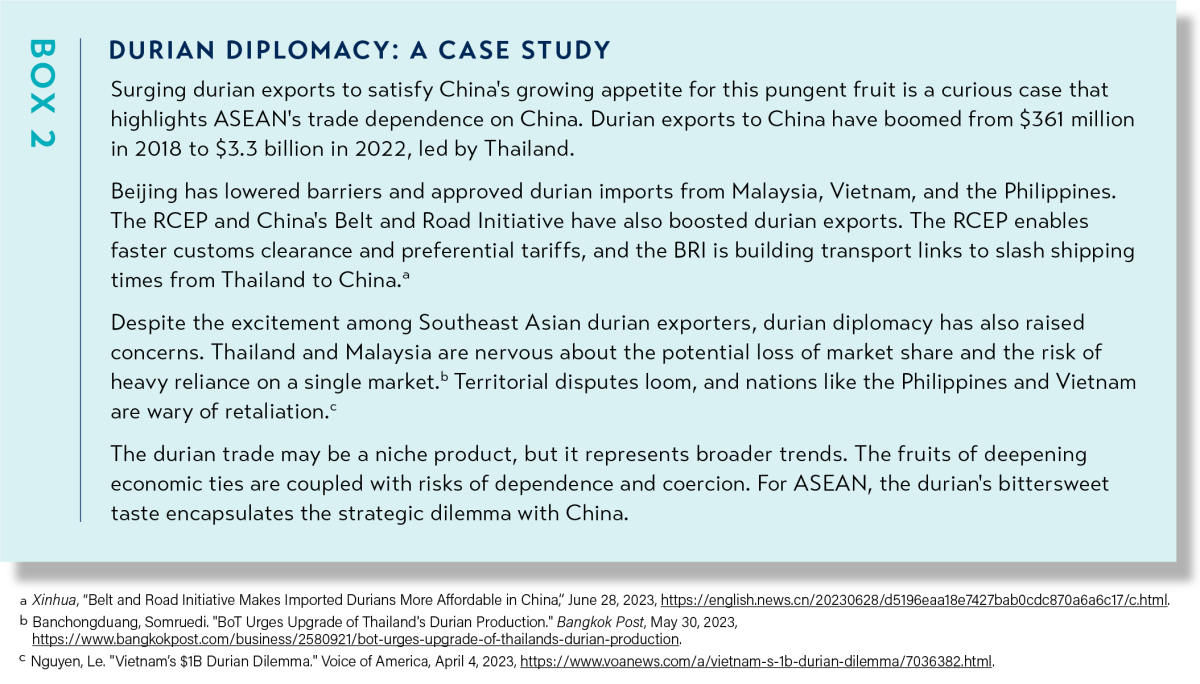

ASEAN's Exports to China: Evolving Links and Risks

China's strategic shift to prioritize domestic production over imports presents a challenge to ASEAN nations. This inward pivot aims to strengthen Chinese industries and curb reliance on foreign suppliers, with ASEAN’s role in “backward Global Value Chains” decreasing since 2011. China is increasingly sourcing these goods domestically rather than receiving unfinished products or raw materials from ASEAN for further processing and re-export.viii Nevertheless, ASEAN’s exports to China continued to rise from $187 billion in 2017 to $291 billion in 2022, increasing its share of ASEAN’s total exports from 12% to 15% over the past decade. More than half the increase came from electronic equipment exports and metals such as ferronickel and stainless steel. Coal and other petroleum products, plastics, and rubber were also significant contributors to this growth, and certain agricultural products such as palm oil and durian fruit increased quickly over this period. This growth reflects China's massive demand as a manufacturing powerhouse and consumer market, and the composition and trends in ASEAN's exports highlight both deepening economic ties and strategic vulnerabilities.

ASEAN capitalized on the unique opportunity presented by the pandemic-induced spike in electronics demand. Between 2019 and 2022, ASEAN's electronics exports to China surged by 60% to nearly $90 billion. Vietnam has been at the forefront of this growth, with its exports of mobile phones and related components more than doubling to almost $18 billion in 2022. Many of Vietnam’s other electronics exports, including video cameras and computer monitors, also grew exponentially. Malaysia and Singapore dominated in exports of semiconductors, which are vital for electronic devices such as computers, smartphones, and TVs. Malaysia also established a strong footprint in data storage exports. Thailand, however, saw its semiconductor exports to China decline by 30% despite overall growth in electronics exports to other countries.

ASEAN’s exports of metals and natural resources to China have been robust and fed China’s industrial expansion, nearly doubling since 2017. Indonesia stands out, with nickel-related exports surging tenfold to a remarkable $23 billion. Indonesia also reported significant growth in other metals such as copper, tin, and aluminum as traditional exports including coal, lignite, and palm oil flourished. Malaysia’s exports of petroleum gases and palm oil saw significant growth, whereas its exports of metals such as aluminum and copper increased exponentially. However, exports of iron ores and tar mixtures declined, possibly due to China’s diversification of its sources.

Exports of food and agricultural products from ASEAN countries to China follow diverging trends. Thailand’s exports, especially fruits, nuts, processed food, sugar, and meat, have skyrocketed. Indeed, fruit exports have grown sevenfold since 2017 to almost $5 billion in 2022. In contrast, Vietnam's traditional food exports have declined, but exports of processed foods and animal feed have increased. Indonesia pivoted to animal feed and fish exports, and both show substantial growth. China's commitment in November 2021 to purchase up to $150 billion worth of agricultural products from ASEAN countries from 2022 to 2026 further underscores the region's potential as a major food supplier to China's market.ix While the overall trend shows a shift toward more value-added agricultural products, the outsized benefits for Thailand and Vietnam underscore the challenges of broadening integration and opportunities for all ASEAN member states.

Exports of plastics and chemicals from ASEAN to China have also varied recently, and the major players — Singapore, Thailand, and Malaysia — follow different trends. Singapore increased its pharmaceuticals and cosmetics exports but had lukewarm or declining chemical and plastic exports. Thailand saw growth in some chemicals but a minimal increase in its plastics sector. Malaysia experienced impressive growth in its plastics, pharmaceutical, and chemicals exports. Indonesia's chemical exports surged, but plastics saw flat growth. Excluding Vietnam, ASEAN's rubber exports dropped significantly as China bolstered domestic production, possibly due to its push for self-reliance or new global competitors. Despite these fluctuations, ASEAN remains an important part of China's plastics and chemicals supply chain.

The more modest growth in the export of plastics, chemicals, machinery, and manufactured goods highlights the risks of China's pursuit of greater self-sufficiency. ASEAN's growing reliance on exporting certain products to China would bring economic and political vulnerabilities should China's policies or demand shift. A case in point is China's resumption of Australian coal imports after a two-year ban, reducing imports from Indonesia.x Significant shifts in demand can occur abruptly due to geopolitical factors, and government policies and supply chains can change suddenly.

ASEAN-China Services Trade: A Growing Dimension

Trade in goods has been the primary focus of ASEAN-China economic ties, but the significance of services trade is growing.xi By 2021, total ASEAN-China services trade exceeded $73 billion, more than tripling from $21 billion in 2009. ASEAN has maintained a slight surplus in services over this period. Services trade with China accounted for more than 10% of ASEAN's total in 2021, up from 6% in 2009 and outpacing ASEAN's global services trade growth.

ASEAN's service exports to China totaled $39 billion in 2021. Leading exports were travel and tourism, but the pandemic triggered a 60% decline in Chinese tourists.xii From 2019 to 2021, Thailand alone saw a $3 billion decrease in travel services exports to China. Over the same time frame, exports of professional and technical services, which include digital services, surged by nearly 60% to $16 billion, with Singapore accounting for more than two-thirds of these exports.

Meanwhile, ASEAN imported more than $32 billion in services from China in 2021, predominantly logistics, construction, telecommunications, and business services. Singapore accounted for almost half of services imports, followed by Thailand and Malaysia.

While still overshadowed by goods trade, growing services trade highlights China’s multifaceted economic role as a major source of tourists and foreign direct investment (FDI), and an emerging services export market for ASEAN.

China's Trade Ties with Select ASEAN Countries

Broader regional trends may influence ASEAN’s export growth, but individual countries exhibit diverse trade dynamics with China driven by unique, local economic factors and policies. Vietnam, for instance, has emerged as China's top trade partner within ASEAN and its fourth largest globally. Vietnam’s exports to China mainly comprise electronics such as telephone parts, raw materials, and agricultural products. Imports from China include electronic goods and components and commodities including steel, fabrics, and plastics, essential inputs for Vietnam's manufacturing sector, along with less expensive Chinese consumer goods. This trade structure explains Vietnam's trade deficit with China having grown from $24 billion in 2017 to $60 billion in 2022 — more than 40% of ASEAN’s total trade deficit.

As China's second-largest trading partner within ASEAN, Indonesia’s trade dynamics have been quite different, with the reported growth in exports to China outpacing its increase in imports. The surge in nickel-related exports, highlighted in Box 3 below, has played a pivotal role in this trade growth. Other drivers have been minerals including tin and aluminum, coal and petroleum products, and palm oil, with Indonesia's exports to China almost tripling since 2017. During that time, Indonesia's imports from China, which include high-tech products, heavy machinery, and equipment, have doubled. China now makes up more than a quarter of Indonesia's total trade, three times the value of its next largest trading partners, Japan and the United States.

Other ASEAN nations, such as Thailand, have cultivated a robust economic relationship with China, fueled by exports of agricultural products and raw materials and imports of machinery and electronic products. Initiatives such as the Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC) and “mini-FTAs”xiii with Chinese provinces have reinforced economic and trade cooperation. Thailand has also attracted considerable Chinese FDI thanks to its status as Southeast Asia’s largest automotive- and auto-parts–manufacturing hub. Major players in China's electric vehicle (EV) industry, like BYD, Changan, and Hozon, have begun to establish factories in Thailand due to its strong automotive industry and its potential as a gateway to regional and Western markets.xiv Despite these positive economic ties, Thailand's dependency on exports to China remains a concern for its business community, which increasingly appreciates the need for diversification to reduce the risk of supply chain disruptions.xv

China's Investments in ASEAN and the Belt and Road Initiative

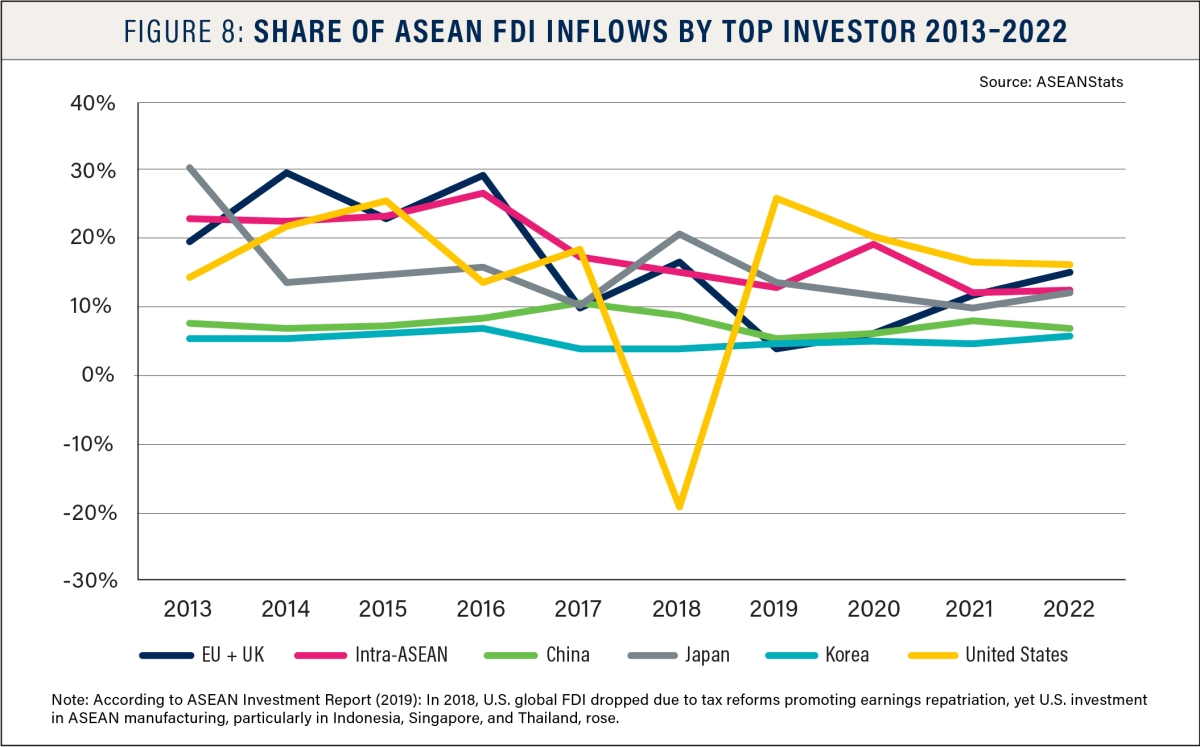

Over the past five years, ASEAN has experienced a 41% surge in overall foreign investment, reaching $223 billion in 2022. The largest beneficiary was Singapore, which set a new record by receiving $141 billion, constituting nearly two-thirds of the total FDI directed toward ASEAN. Malaysia, Vietnam, and Indonesia also attracted considerable investment, whereas the Philippines saw a decline, mainly attributed to domestic investors acquiring foreign affiliates.xvi

Chinese investment flows into ASEAN have grown, despite a general global downturn in Chinese FDI since 2016 due to regulatory factors and tightening investment screening measures in advanced economies. However, Chinese FDI remains relatively modest compared to partners such as the United States, the European Union, and Japan. In 2021, China accounted for just 3% (or 8%, if Hong Kong FDI is included) of the total FDI stock in ASEAN, with estimates ranging between $100 billion to $133 billion, based on various data sources.xvii The United States remained the most significant investor with 23% of the total FDI stock in the region.xviii Shifting focus to the annual investment flows for 2022, the United States continued its significant contribution, accounting for 16.3% of the total investment in ASEAN, equating to $36.6 billion. In the same year, China's annual investment flow was approximately 7% or $15.4 billion, a substantial increase from its pre-pandemic level of $9 billion in 2019.

China's investment focus in ASEAN has undergone a transformation. Historically characterized by low value-added manufacturing and real estate, recent increases in Chinese FDI have shifted toward more advanced manufacturing, processing of critical raw materials, and investments in technology and the digital economy.xix Chinese FDI in ASEAN manufacturing has tripled since 2017, reaching more than $5 billion in 2022 to account for nearly a quarter of all Chinese FDI in ASEAN over this time frame.

The largest beneficiaries of China's investments are Singapore and Indonesia, and Cambodia receives the most substantial Chinese investments as a proportion of its total FDI. However, Singapore's dominant position is an exception, reflecting its role in investment routing and round tripping due to its status as a major tax and investment hub. Indonesia's prominence is driven by large projects, representing more than two-thirds of the total Chinese FDI stock and concentrated in the extractives and infrastructure sectors.xx

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) provides another avenue for China's regional economic expansion. The BRI is focused on infrastructure development aimed at boosting regional connectivity. This encompasses a range of initiatives, from ports and railways to power projects. Although the BRI plays a significant role in China's strategy in ASEAN, it is important to distinguish it from typical FDI. BRI financing is diverse and often includes not only FDI but also mechanisms such as official development assistance (ODA) and other official flows (OOF).

In recent years, the BRI has made significant inroads into Southeast Asia, with 131 projects between 2013 and 2021. Countries including Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, the Philippines, and Vietnam have been the primary beneficiaries.xxi Initially, these projects were predominantly centered on strategic infrastructure projects such as ports, railways, mining, and power plants. However, the health sector and the digital economy are gaining increasing attention. This flags a shift in China's investment strategy within the ASEAN region.

The Role of the RCEP in Shaping ASEAN-China Trade

The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) between ASEAN, China, and four other Asia-Pacific economies came into effect in January 2022. It is the world's largest regional FTA and comprises about 30% of global GDP and 30% of the world's population. The agreement aims to stimulate regional integration through tariff cuts, simplified customs procedures, and reductions in nontariff barriers.

Some economists project that the RCEP will increase ASEAN’s exports, mainly from manufacturing, by $78 billion in 2030,xxii due to deepened regional production networks and increased productivity. The bloc’s trade-oriented economies — Vietnam, Thailand, and Malaysia — gain the most in percentage terms and along with countries like Cambodia and Laos that will benefit from integration into regional supply chains. Tariff liberalization and improved rules of origin are significant drivers, yet much of the RCEP’s impact will depend on reductions in nontariff barriers.

Despite these potential benefits, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) notes that the RCEP’s complicated rules and processes, which include 38 different plans for adjusting tariffs over a lengthy 20-year period, could discourage firms from taking advantage of the RCEP’s trade preferences.xxiii The ADB underscores that realizing the RCEP's potential hinges on its effective implementation and continuing efforts to strengthen the agreement.

ASEAN countries face risks, including competition with highly efficient Chinese exporters, that could lead to widening trade deficits and potentially weaken domestic industries. One study indicates that tariff liberalization under the RCEP will likely result in a surge in imports from China to most ASEAN countries and a drop in ASEAN’s exports to China, leading ASEAN’s balance of trade to deteriorate relative to other RCEP countries by 6% a year.xxiv Furthermore, the RCEP may reduce intra-ASEAN trade commerce as members import more from China than from one another. Indeed, ASEAN countries such as Vietnam and the Philippines have expressed apprehensions that the agreement might exacerbate their already growing trade deficits with China, the RCEP’s largest economy.xxv

Impact of U.S.-China Tensions on ASEAN

ASEAN is deeply affected by the fluctuations in the U.S.-China trade relationship. While U.S.-China trade reached record highs in 2022, U.S. imports of Chinese products hit with 25% tariffs during the trade war have declined sharply.xxvi In the first half of 2023, China's share of U.S. imports plummeted to levels last seen in 2003.xxvii This reduction in U.S.-China trade directly impacts ASEAN because many ASEAN exports to China eventually find their way into U.S. markets after further processing or assembly. Slower economic growth in the United States and China also negatively impacts ASEAN economies since these countries are their largest export markets.

Shifting global trade dynamics, however, also present opportunities for ASEAN. Companies’ pursuit of diversification has led several Southeast Asian nations to position themselves as alternative production hubs, particularly for businesses seeking to minimize their reliance on China. From 2018 to 2022, ASEAN's share of the value of U.S. imports rose by 3%, whereas China's share fell by 4%. During this period, all ASEAN economies, except for Singapore and Brunei, expanded their shares of U.S. imports.xxviii Yet ASEAN's trade with China also increased from 17% of ASEAN’s total trade in 2018 to almost 19% in 2022.

These shifts support findings from a recent study that the trade war has not only redirected trade but also expanded trade opportunities for many countries in Southeast Asia.xxix ASEAN nations have boosted their exports to the United States and the rest of the globe, and they report greater export growth rates for products subjected to U.S. tariffs against Chinese imports than those that were not. For example, Vietnam, Thailand, and Malaysia have increased their exports of goods affected by the trade dispute and demonstrated themselves as viable alternatives. This could have longer-term supply chain implications.

Some economists estimate that if the current tariffs persist, the United States and China will bear the brunt of the impact. China's RCEP competitors, including ASEAN, could experience modest export gains.xxx Vietnam, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand may see slight increases in exports, while Singapore and Indonesia face potential marginal declines.

Expanding on these potential outcomes, a simulated "decoupling scenario" — whereby U.S.- and China-led blocs imposed additional trade barriers against each other — showed ASEAN benefiting economically by remaining neutral, increasing GDP by about 1% and facing economic repercussions if it sides with either bloc. Either China or the United States would be adversely affected if ASEAN aligned with the opposing side. This result underscores the incentives for ASEAN to maintain neutrality amid U.S.-China tensions.xxxi

ASEAN's Trade Dependence on China: A Growing Concern

As the largest economy in Asia, China’s economic performance has a significant impact on the economies of its neighbors. With the emergence of new and enhanced regional trade agreements and deepening ties of trade and investment, ASEAN's economies are linked more than ever to China’s. According to the Asian Development Bank, in 2000 a 1% increase in China's economic output led to a 1.7% rise in ASEAN's output. A 1% increase in Chinese output led to a 4.9% increase in ASEAN output in 2010 and a 6.3% increase in 2020. ASEAN countries enjoy significant benefits when China's economy grows, but they also face greater vulnerabilities during China's economic downturns.xxxii

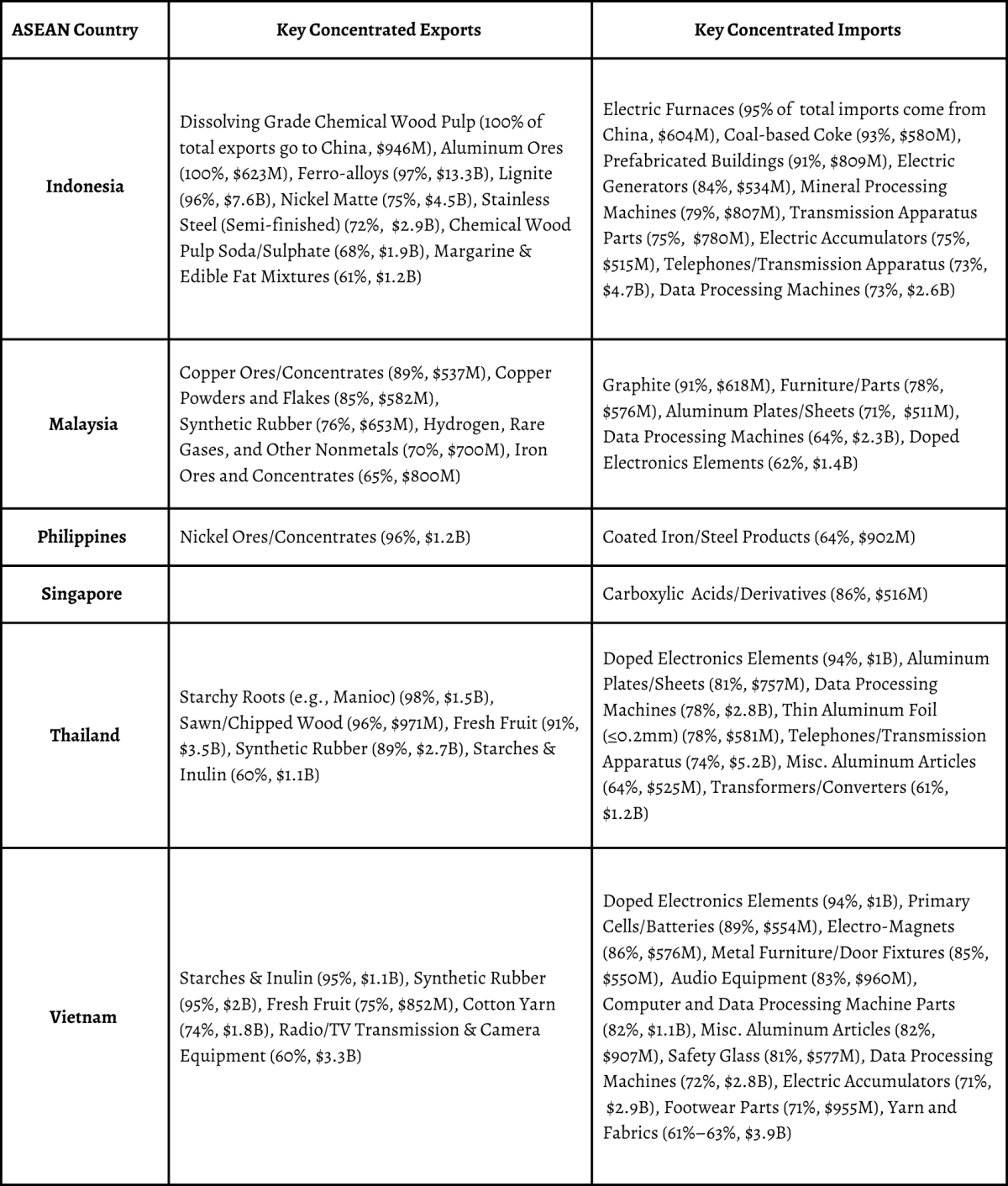

ASEAN’s imports from China have led to a sizeable and growing trade deficit, reaching $140 billion in 2022 — nearly 4% of ASEAN's overall GDP. Trade deficits arise for a variety of reasons and are not inherently a problem, but they can also be symptomatic of other concerns, including overreliance on particular sources for certain products. Appendix 1 presents a closer examination of trade concentration for key imported and exported products.

Vietnam and Thailand account for most of ASEAN’s deficit with China, underscoring their reliance on Chinese imports. The Philippines and Malaysia have also seen their deficits grow, reflecting a broader regional trend of mounting trade imbalances with China. Among smaller ASEAN economies, Cambodia's situation is particularly alarming — its trade deficit with China soared to 30% of its GDP in 2022.

A recent ISEAS survey of Southeast Asian experts and opinion makers indicates unease about the one-sidedness of these trade relationships.xxxiii China was identified as the most influential economic power by 60% of respondents, and nearly 80% of respondents from countries with significant deficits, including the Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam, and Myanmar, reported concerns about this influence. This finding highlights the nuanced dynamics of the ASEAN-China relationship. The 2012 incident when China suddenly banned Philippine banana exports during a maritime dispute over the Scarborough Shoal in the South China Sea serves as a stark reminder of the potential for economic coercion.xxxiv

Recent Developments: A Slowing Chinese Economy and its Impact on ASEAN Trade

Recent economic shifts have underscored worries about ASEAN's overreliance on trade with China and the potential challenges that might arise. China's post-COVID economic rebound has shown signs of slowing, with growth decelerating by more than 3.2% in the second quarter of 2023 due to a weakening property market, sagging consumer spending and investment, lagging exports, and deflationary concerns.xxxv This downturn has resulted in notable shifts in the ASEAN-China trade relationship, with goods trade declining by almost 5% in the first half of 2023 compared to the same period in 2022.

ASEAN's imports from China plunged 13.5% in the second quarter of 2023, with broad declines across numerous categories including electronics, machinery, plastics, and steel. Decreased demand in major markets such as the United States and Europe is also indirectly reducing demand for China's intermediate inputs into ASEAN's exports. Concurrently, ASEAN's exports to China fell more than 3%, as Chinese manufacturers reduced imports of industrial materials across a wide range of products including steel, plastics, rubber, and organic chemicals. There were some exceptions — ASEAN's energy exports to China surged by more than 20% and fruit exports jumped by 35%.

Given China's critical role as ASEAN's largest trade partner, this deceleration has had tangible economic impacts across ASEAN. For instance, Vietnam, a major exporter of textiles and electronics, reported a 14% drop in exports in the second quarter in 2023 from the previous year. Malaysia's economic growth hit its slowest pace in nearly two years, largely affected by China's slowdown. Meanwhile, Thailand's economic growth was hindered not only by internal political challenges and decreased tourism from China but also by reduced export demand for intermediate products, such as electronics components.xxxvi

Policymakers should focus on striking a delicate balance between the advantages of trading with China against the risks stemming from overdependence. A multifaceted strategy focused on supply chain diversification, deeper intra-ASEAN economic integration, and strengthened external partnerships can increase ASEAN's strategic flexibility and set the stage for a more resilient, sustainable economic future.

- Enhance Diversification Efforts: Diversification of trading partners to mitigate the risks posed by overreliance on China should be a cornerstone of ASEAN's approach. This would diminish ASEAN's vulnerability to external shocks and offer a reliable alternative for businesses relocating from China. ASEAN members must make it easier and less costly for companies, especially small and medium-sized businesses, to move into new markets and to source goods from a broader range of suppliers.

- Strengthen Intra-ASEAN Trade and Beyond: Policymakers should prioritize expanding intra-ASEAN trade and supply chain integration, especially in the electronic, automotive, and apparel sectors. By localizing supply chains, ASEAN can lessen its dependence on imports for components and materials and emerge as a global supplier. Engaging more proactively with dialogue partners will help further diversify and enhance ASEAN's trade network.

- Pursue Strategic Trade Agreements: Countries in Southeast Asia should also actively pursue bilateral and regional trade agreements to enhance their trade relationships with a varied set of partners. Recent initiatives, such as the Philippines-Korea FTA signed in September 2023 and the ongoing negotiations for the ASEAN-Canada FTA, are useful steps in this direction. However, joining high-standard agreements like the CPTPP would have an even greater impact. For instance, if additional major ASEAN economies such as Indonesia, the Philippines, and Thailand became CPTPP members, they could boost their exports by an estimated $35 billion.xxxvii Furthermore, this would not only grant them greater access to significant markets, including Japan, Canada, and Mexico, but also promote trade diversification and integration into sophisticated supply chains.

- Expand Market Access to China: Policymakers should explore strategies to deepen market access and reduce trade barriers that could boost exports to China. They could leverage the RCEP and secure additional market access commitments in the ongoing ACFTA 3.0 negotiations.

- Balance China's FDI with Sustainability and Local Capacity: China's FDI brings needed investment into ASEAN countries, but policymakers must ensure that Chinese investments align with ASEAN's sustainable growth goals. Greater emphasis on transparency, accountability, and local capacity building would be a step in the right direction.

U.S. policymakers should pay close attention to the region’s shifting investment and trade trends, particularly between ASEAN and China. U.S. strategies should include shaping regional trade networks, enhancing investment in sectors where the United States has a competitive edge, and bolstering ASEAN's capacity. The United States should also establish new partnerships within ASEAN and leverage the private sector to help countries diversify their markets and reduce dependence on any single economy. These strategies can offer a positive alternative to China's assertive trade policies and ensure sustained U.S. relevance in the region.

Appendix

Appendix 1. ASEAN-China Trade Concentration for Select Products (2022)*

*Percentage figures refer to the share of total global exports/imports for that product that go to/come from China

End Notes

[i] Unless otherwise noted, all trade and foreign direct investment (FDI) data used in this issue paper are derived from ASEANStats. https://data.aseanstats.org/.

[ii] International Monetary Fund, "World Economic Outlook: April 2023," https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2023/April.

[iii] International Monetary Fund, "World Economic Outlook: April 2023," https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2023/April.

[iv] International Monetary Fund, "Direction of Trade Statistics." Accessed from IMF Data, https://data.imf.org/?sk=9d6028d4-f14a-464c-a2f2-59b2cd424b85.

[v] “DHL Trade Growth Atlas 2022,” https://www.dhl.com/global-en/delivered/globalization/dhl-trade-growth-….

[vi] Boston Consulting Group, "How ASEAN Can Use Its Trade Advantage to Power Ahead," May 3, 2023, https://www.bcg.com/publications/2023/asean-free-trade-advantage-to-pow….

[vii] Author analysis of UN Comtrade Broad Economic Categories, https://comtradeplus.un.org/.

[viii] Asian Development Bank, "ASEAN and Global Value Chains: Locking in Resilience and Sustainability," March 2023, 64, https://www.adb.org/publications/asean-global-value-chains-resilience-s….

[ix] Iwamoto, Kentaro, and Tan, C. K., "Xi Courts ASEAN at Summit as Duterte Hits Out over South China Sea," Nikkei, November 22, 2021, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/Xi-courts-ASEA….

[x] Russell, Clyde. "China's Renewed Appetite for Australian Coal Disrupts Asia Flows," Reuters, August 10, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/chinas-renewed-appetite-aus….

[xi] Data on services are derived from the OECD-WTO Balanced Trade in Services dataset, https://stats.oecd.org/.

[xii] “Landscape Study on Southeast Asia’s Aviation Industry: COVID-19 Impact and Post-Pandemic Strategy," May 2023, Asian Development Bank, https://www.adb.org/publications/southeast-asia-aviation-covid19-post-p….

[xiii] Thailand has signed mini-FTAs with several Chinese provinces to expand trade and investment. These agreements focus on small and medium-sized enterprises support, trade facilitation, business matchmaking, and boosting e-commerce alongside agricultural and industrial products trade.

[xiv] The Economist, "Why Chinese Carmakers Are Eyeing Thailand," May 11, 2023, https://www.economist.com/business/2023/05/11/why-chinese-carmakers-are….

[xv] Bangkok Post, “Horns of a Dilemma,” June 26, 2023, https://www.bangkokpost.com/business/2599545/horns-of-a-dilemma.

[xvi] UNCTAD World Investment Report, 2023, https://unctad.org/publication/world-investment-report-2023.

[xvii] Discrepancies in 2021 investment figures arise from different sources: MOFCOM reports $133 billion, ASEAN statistics indicate $109 billion, and Rhodium's cumulative transactional data suggest $100 billion. Source: Mingey, Matthew, Parker, Benjamin, Zou, Chris, Gormley, Laura, and Marshall, Hope, "ESG Impacts of China’s Next-Generation Outbound Investments: Indonesia and Cambodia," August 24, 2023, https://rhg.com/research/esg-impacts-of-chinas-next-generation-outbound…

[xviii] Xavier, Denis, "Foreign Direct Investment Flows in South-East Asia: A Region between China and the United States." Banque de France Bulletin, May-June 2023, https://publications.banque-france.fr/en/foreign-direct-investment-flow….

[xix] Mingey, Parker, Zou, Gormley, and Marshall. "ESG Impacts of China’s Next-Generation Outbound Investments.”

[xx] Mingey, Parker, Zou, Gormley, and Marshall. "ESG Impacts of China’s Next-Generation Outbound Investments.” -

[xxi] Nouwens, Meia. "China’s Belt and Road Initiative A Decade On," Chapter 4 in Asia-Pacific Regional Security Assessment 2023, International Institute for Strategic Studies, https://www.iiss.org/en/publications/strategic-dossiers/asia-pacific-re….

[xxii] Park, Cyn-Young, Petri, Peter A., and Plummer, Michael G. "The Economics of Conflict and Cooperation in the Asia-Pacific: RCEP, CPTPP and the U.S.-China Trade War," East Asian Economic Review 25, no. 3 (September 2021): 233–272, https://dx.doi.org/10.11644/KIEP.EAER.2021.25.3.397.

[xxiii] Crivelli, P., and Inama, S., "A Preliminary Assessment of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership," ADB Briefs no. 206 (2022), Manila: Asian Development Bank, https://www.adb.org/publications/assessment-regional-comprehensive-econ….

[xxiv] Banga, R., Gallagher, K. P., and Sharma, P., "RCEP: Goods Market Access Implications for ASEAN," Global Development Policy Center, Working Paper No. 045, Pardee School of Global Studies/Boston University, March 2021, https://www.bu.edu/gdp/files/2021/03/GEGI_WP_045_FIN.pdf.

[xxv] Le Thu, Huong. "Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, ASEAN’s Agency, and the Role of ASEAN Members in Shaping the Regional Economic Order," ERIA Discussion Paper Series No. 448 (2022), Jakarta: Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia, https://www.eria.org/publications/regional-comprehensive-economic-partn….

[xxvi] Bown, Chad P., "U.S. Imports from China Are Both Decoupling and Reaching New Highs. Here's How," Peterson Institute for International Economics, March 31, 2023, https://www.piie.com/research/piie-charts/us-imports-china-are-both-dec….

[xxvii] DeBarros, Anthony, and Hayashi, Yuka, "How U.S. and China Are Breaking Up, in Charts," The Wall Street Journal, August 12, 2023, https://www.wsj.com/articles/how-u-s-and-china-are-breaking-up-in-chart….

[xxviii] U.S. Census Bureau, USA Trade Online, https://usatrade.census.gov/.

[xxix] Fajgelbaum, Pablo, Goldberg, Pinelopi, Kennedy, Patrick, Khandelwal, Amit, and Taglioni, Daria, "The ‘Bystander Effect’ of the U.S.-China Trade War," Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR), June 10, 2023, https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/bystander-effect-us-china-trade-war.

[xxx] Park, Petri, and Plummer, "The Economics of Conflict and Cooperation in the Asia-Pacific.”

[xxxi] Isono, Ikumo, and Kumagai, Satoru, "ASEAN’s Role in the Threat of Global Economic Decoupling: Implications from Geographical Simulation Analysis," Policy Brief, Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia, no. 2022-10 (February 2023), https://www.eria.org/publications/aseans-role-in-the-threat-of-global-e….

[xxxii] Asian Development Bank, "ASEAN and Global Value Chains: Locking in Resilience and Sustainability," March 2023, 91–92, https://www.adb.org/publications/asean-global-value-chains-resilience-s….

[xxxiii] ASEAN Studies Centre, "The State of Southeast Asia 2023 Survey," ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, 2023, https://www.iseas.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/The-State-of-SEA-20….

[xxxiv] In 2012, China tightened quarantine restrictions on Philippine banana imports that led to extended delays and produce rotting in ports. Beijing cited phytosanitary standards, but these abrupt trade curbs were widely perceived as economic retaliation against Manila's territorial claims. This incident underscores China's strategic use of trade during political disputes. Higgins, Andrew, "In Philippines, Banana Growers Feel Effect of South China Sea Dispute," The Washington Post, June 10, 2012, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/in-philippines-banana….

[xxxv] "Why China’s Economy Won’t Be Fixed," The Economist, August 24, 2023, https://www.economist.com/leaders/2023/08/24/why-chinas-economy-wont-be….

[xxxvi] White, Edward, and Song, Jung-a in Seoul, "China’s Economic Slowdown Reverberates across Asia," Financial Times, September 2, 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/ae3c146f-5752-4d04-8a62-d7957a85f542.

[xxxvii] Asian Development Bank, "ASEAN and Global Value Chains: Locking in Resilience and Sustainability," March 2023, 289, https://www.adb.org/publications/asean-global-value-chains-resilience-s….