ASPI Note: Is China Trying to Establish a Military Base in the Pacific?

What’s Happening: Last Thursday, a draft memorandum of understanding between the Pacific island nation of Solomon Islands and China was leaked online by opponents of the deal. The agreement, which has since been verified, provides a foothold for Solomon Islands to request “China to send police, armed police, military personnel and other law enforcement and armed forces…to assist in maintaining social order, protecting people’s lives and property” and for China to “make ship visits [and] to carry out logistical replenishment in Solomon Islands.” This has fueled speculation that China is seeking to establish a permanent military presence in the Pacific islands.

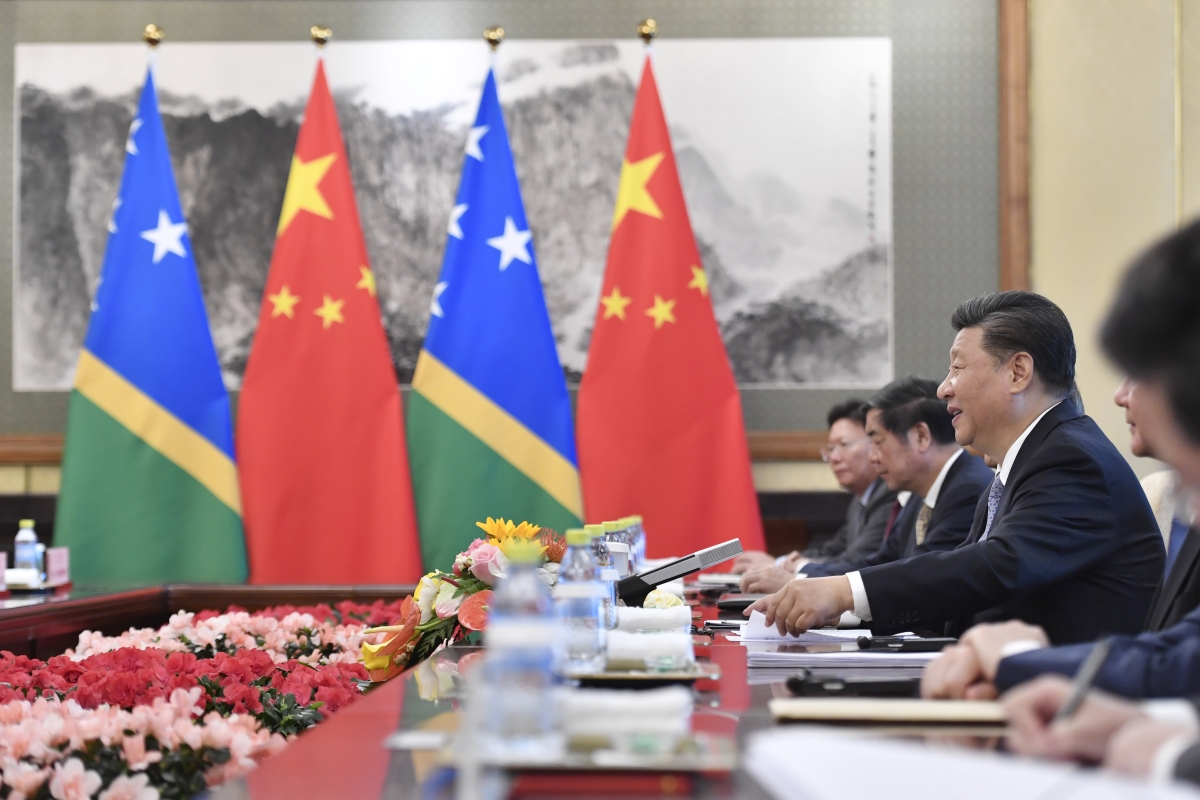

The Background: In 2019, just months after Manasseh Sogavare became prime minister of Solomon Islands for the fourth time, the country switched its recognition from Taiwan to the People’s Republic of China and signed up to the Belt and Road Initiative — Xi Jinping’s signature foreign policy initiative.

Economic relations between the two countries were already strong with China being the largest export destination for Solomon Islands.

However, since then, China has rapidly built up its development aid and finance for Solomon Islands. The China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation was awarded the contract to build a large number of facilities for the 2023 Pacific Games to be held in the capital Honiara — Sogavare’s own signature initiative. And Chinese companies are also building bridges and roads, have taken over a gold mine, and tried to lease the entire island of Tulagi.

Reports of bribes and kickbacks, including for members of the Solomon Islands parliament, have been commonplace. This, and a perception Beijing’s support has focused heavily on the capital island of Guadalcanal (where American troops waged a famous battle in World War II), as opposed to the more populous island of Malaita, has sparked protests in late 2021 that saw Sogavare’s residence attacked and shops set on fire in Honiara’s Chinatown, which resulted in the deaths of three people.

Why it Matters: While the agreement does not explicitly establish a permanent military presence in Solomon Islands, it is seen by many as a precursor to this. China currently only has one overseas military base in the African nation of Djibouti, though there have been recent reports of Beijing’s interest in establishing another on the West African coast. The United States has a number of military outposts in the region, including in the Compact of Free Association states.

The geopolitical significance of a Chinese naval base in Solomon Islands is profound, especially given the implications for open access to the sea lanes for communication in the Pacific, including by western naval vessels.

Solomon Islands is also less than 1,500 miles to Australia’s northeast, where political anxieties over China’s rise have already reached a fever pitch — Beijing has effectively frozen relations with Canberra in recent years in response to Australia’s stance on Chinese foreign interference and outspokenness on foreign policy matters.

The agreement is also significant given the Pacific Islands have long been a stronghold for diplomatic recognition of Taiwan. In 2019, the island nation of Kiribati also switched its recognition to Beijing where support for the upgrading of a remote airstrip sparked similar speculation last year of a possible Chinese military presence — these were ultimately rejected. Only four Pacific Island nations now remain amongst the 14 states that recognize Taiwan (Marshall Islands, Palau, Nauru, and Tuvalu).

What is Likely to Happen: Australia has been careful to balance its reaction to the draft agreement thus far. Australia’s High Commissioner in Honiara was dispatched to meet with Sogavare and there have been calls for Australia’s foreign minister to also visit. Solomon Islands’ opposition leader Matthew Wale has also warned Canberra of the impending deal last year.

On the one hand, Canberra does not want to be seen to be interfering with the sovereign decision of a Pacific Island nation — a region where it has launched a “step up” in its engagement in recent years, albeit held back by their position on climate change, which is an existential issue for these nations. This would also play into Sogavare’s own political desires to rally against perceived Australian heavy-handedness — he has already labeled critical reaction to the deal as “very insulting” and said it is part of his country’s attempts to “diversify” its security partners.

At the same time, Canberra will be alarmed by any prospect of a Chinese regional presence, and the conservative government is likely to lean heavily on national security during the imminent federal election campaign.

As it often does in the Pacific Islands region, the United States is likely to follow Australia’s lead on the matter. Washington closed its embassy in Honiara in the 1990s, but recently pledged to reopen it.

In the short term, the biggest risk is the deal could spark further domestic uprising. Australian and other regional military and police forces have been re-deployed to Solomon Islands in recent months at Honiara’s request and are likely to remain until the 2023 elections. Between 2003 and 2017, a large number of regional forces were also deployed to the country as part of the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (RAMSI).