magazine text block

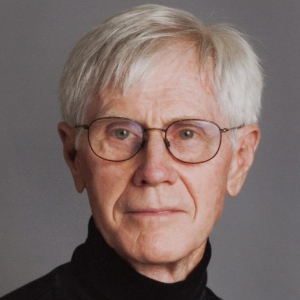

Orville Schell, founder and director of Asia Society’s Center on U.S.-China Relations, has spent six decades focusing on China as a scholar, journalist, author, and advocate. He sat down in his Berkeley, California, home to talk with Mary Kay Magistad, associate director of the Center on U.S.-China Relations and a former China and East Asia correspondent for NPR and PRI/BBC’s The World.

magazine text block

You made your first trip into China in 1975, at the tail end of the Cultural Revolution. What was that like?

I got invited to go on a trip that had been approved by Premier Zhou Enlai. He was part of a contingent of leaders who believed that China did need to open up somewhat, and become more practical and less political. And he was, in a certain sense, a counterforce to Chairman Mao. He had allowed a few trips to come in, organized by a fellow traveler, Bill Hinton, who had been in China since the 1940s, when he was there in the United Nations Relief Administration. I got included, even though I was writing for The New Yorker at the time. That was a real wake up call for me, because of course I was very excited to go, but I thought that I had some fundamental notion about how to interact with Chinese people and I spoke some Chinese. And yet when I got to China, it was utterly insoluble.

When they found out I was writing for The New Yorker, they became very nervous. At one point, when I was working in Dazhai, the model agricultural brigade, they put me in a cave and didn’t let me out for several days. They told me I was sick, that I needed to stay there and get well. What was actually going on was that they knew that I was a writer, and they didn’t quite know how to deal with that. Here I was on this fraternal youth work brigade — we were allegedly working, but of course, just basically impeding progress — and this was not what they had in mind, that someone was going to write about the experience.

Again and again, if I would wander off to another village to talk to people, they’d come and get me. I remember one time I met this wonderful man, a doctor. He was taking care of fruit trees at the brigade. And I said, “I’d love to come and see what you do.” He said, “OK.” But when the authorities found out that he and I had connected directly, they immediately turned on him and criticized him. That’s when I got locked up.

So it was a real wake up call for me. I didn’t quite know what was going on, but I knew something wasn't right.

magazine quote block

magazine text block

This was in the last year or so of the Cultural Revolution, 1975-76. What were people saying to you about what was going on?

We got plunged into criticism sessions and study sessions where we’d study and criticize Confucius and Lin Biao. Confucius was meant to be a stand-in for Zhou Enlai, a kind of a Mandarin, as cosmopolitan as they got in leadership.

Chinese facilitators would hold these meetings, and we’d read these documents. Many people on my trip were very naive. They knew nothing about China, and were quite leftist to boot. And there was a lot of pressure to conform to these official views. It was important and interesting for me to participate in that, and to understand what that’s like, that when the prevailing wind is blowing, you can oppose it, but you’re going to end up getting locked in your cave. It was a light version of what I think was the Chinese experience — very censorious, very intimidating.

When you went home from that visit, did it change how you thought about how you’d engage with China from that point on?

Well, it was a very bewildering experience, in many ways. But then of course, it wasn't so many years after that when China started to open up, in the late ’70s. And from that point on, I visited often. I continued writing for The New Yorker as this amazing process unfolded, trying to make sense out of it. How did the Cultural Revolution generate Deng Xiaoping and his reforms? And where was it going? When Deng came in, in ’78 and ’79 and waved his wand, and seemed to cancel the past, I remember thinking “not so fast.” You don't go through years of tectonic class struggle and revolution and just wave it away. It gets into your DNA somehow, and it will re-express itself in some way going forward. And I think that’s exactly what’s happening now.

Did you also see it happening in the ’80s, which was otherwise considered to be a pretty open time?

I did. Even though it was an immensely exciting time, where things were really open in a way that I never could have foreseen in 1975, I was painfully aware that within that reform movement, there was a steel shank of one-party rule that never was dissolved. Deng Xiaoping himself basically said the Party is the center, and everything grows out of the Party — and don’t forget it. So even as Deng was catalyzing all of these reforms and marketization and intellectual openness, and elections even — that basic core operating system never changed.

I’ve heard people in China talk about how robust the conversations were in the ’80s, that there were salons and universities and that it really felt like political reform was possible, in addition to the economic reform that was happening in the countryside and helping farmers lift themselves out of poverty.

It was extraordinary, what happened in the ’80s. People could basically publish almost anything. All kinds of Western works were being translated — including television programs and history programs. Some of them were very exciting, innovative, and interesting. There was an intellectual yeastiness that matched the sort of marketization of the economy. And then you had figures like Fang Lizhi, the great astrophysicist, who in ’86 and ’87 went abroad and started writing about his experiences, and then went across China on an incredible tear, speaking at every major university in the most intelligent but provocative way, saying that China needed to get rid of its one-party system and become a democracy to become a truly modern society. And they kicked him out of the Party. But they didn't do anything more than that.

Orville Schell works at the Shanghai Electrical Machinery Factory while on assignment for The New Yorker in 1975.

Richard Gordon

magazine text block

The Tiananmen protests came out of this era. Did it surprise you that so many people took to the streets?

Yes. There were earlier student demonstrations, in 1986-87, and that’s why Hu Yaobang fell as the Party’s general secretary, and Zhao Ziyang came in. But the scale of the Tiananmen protests nonetheless did surprise me. You could feel there was some disaffection, with inflation, corruption, and other things. And then everybody piled on. The permissive environment that the Party had allowed up until then made people feel that the costs of participating would not be high. It was a time of amazing optimism and openness, and the sense that maybe history actually was going to change, and the Party actually would allow a more tolerant sort of society to evolve.

Were you there for the protests?

Yes, for weeks. Interestingly, in April 1989, we were having a conference out here in California, in Bolinas, with about 30 Chinese intellectuals and American scholars on exactly the topic of what was the intelligentsia thinking and where was it all going to go. There were all kinds of people like Chen Kaige and Liu Binyan and Wu Zuguang, people who were notable intellectual figures at the time. And then the demonstrations began to erupt with the death of Hu Yaobang. Fang Lizhi was phoning in from Beijing at night to tell us what was going on. After this conference ended, we all jumped on planes and went back to China. Then the protests started to get Party pushback and push came to shove, and we know what happened in the end. It got very dark and very brutal. It was shocking. It was literally unbelievable that it would happen. On the other hand, power grows out of the barrel of a gun, and the Party has the gun.

What did you make of what you were seeing over those next couple of decades, the ’90s and the early 2000s, that saw the emergence of an increasingly prosperous and powerful China? What was it saying to you that this was happening alongside the fact that the Tiananmen crackdown had happened?

I thought that China was engaged in an amazing experiment. And I wasn’t sure how it was going to work out. The covenant was: You can become wealthy and have a better life — just keep your nose clean politically. And I wasn’t sure that was going to work, because having seen the wellspring of sentiment that had erupted in the ’80s, and particularly in 1989, it seemed unlikely that they could tamp that down. In retrospect, I think they actually were quite successful. But I’ve learned over the years that China is a very bipolar proposition. It has within it these sort of opposite tendencies that wax and wane. At any moment, it looks like only one side is there. But the other side is incipient. And so I think even now where marketization has come to kind of a curious moment, freedom of expression and dissenting views are largely suppressed, it doesn’t mean that that ability, that tendency is completely erased from the sort of historical genome, and won’t come out again, sometime.

China’s relationship with the United States has swung from one direction to another as well. What do you make of how we got to where we are at the moment?

Just as China has been through very different totalistic phases of shut down and opening up, of suppression and of a freer environment, so too, it’s been through some very extreme versions of the love/hate, attraction/repulsion mechanism with the United States. And I think both are profoundly deep in China. There is a tremendous fascination with America, and affection for America, that goes back more than a century. And yet there’s also a deep and abiding uneasiness about being too slavishly admiring, or under the shadow of America. There’s an expression in Chinese — that “the American moon is rounder than the Chinese moon” — that really rankles many Chinese people.

magazine quote block

magazine text block

Do you think the Chinese government has a blind spot in terms of recognizing what people around the world actually want, and how much that’s going to matter, in terms of whether China can really be the kind of power its leaders want it to be?

I think that the PRC’s form of autocratic rule has a certain logic. And maybe some of it should be maintained in a country as big and difficult to govern as China. But an awful lot of it is excessive and, it seems to me, tremendously counterproductive, and not in the interest of a ruling party. Why piss everybody off unnecessarily, either within your country by being too repressive, or abroad, by having too much of a “wolf warrior” diplomacy, just because you can throw your weight around? I think this is where there’s a profound, structural weakness in what the Party is doing.

What do you think is a robust way that the United States can engage with China, deal with China, and counter China in the world? What’s the right balance?

In a certain sense, the best remedy is to be strong ourselves in every way — militarily, culturally, technologically, economically, you name it. We should also weave together, as tightly as possible, a fabric of allies, partners, and friends who share common principles and forms of governance — a rules-based world order. But at the same time, we should keep the doors as wide open as possible, not trying to change the way the Chinese live or govern themselves, but also not engaging if it’s not in our interest. But we can’t do it alone. China loves to deal with people bilaterally, and pick them off and kneecap them.

We should also recognize there are areas where we really should cooperate. If we’re going to lead, we have to lead. To lead, you have to take chances. And you have to always make it clear that there is a way that we could foresee collaborating and cooperating.

The tragedy is that starting in 1972, we had just such an operating system. We called it “engagement,” and it worked — not perfectly, but by and large, it worked. We didn't see China as an enemy. But then Xi Jinping came along, and suddenly we began to see each other as hostile foreign forces.

What is it that you think is important for Americans, in particular, to understand about Chinese culture, and how Chinese people see the world?

There are qualities in many Chinese people that I know — such as my friends, and I certainly experienced it in my marriage — that are really extraordinary and esteemable. So I think the real problem is the different forms of governance, and different sort of state-sponsored values. I just, frankly, do not believe that governments need to be bullies, to push people around and lock people up. Yes, it’s messy to be democratic. China doesn’t have to be completely democratic, but it should be a little more democratic. That's the best way to be.

China’s challenge is to find some middle path. And that’s exactly what China has not been able to find under the Chinese Communist Party, a more temperate balance point in the middle that may be somewhat messier, but is perhaps more durable, and will prevent them from having to lurch from one extreme to another. Mao’s revolution did this, and it was terribly destructive. What a great tragedy it would be now, if China’s extremism destroyed its whole economic miracle, and if it alienated all of the countries around it in the world — countries like the United States, Australia, Canada, and India. Who alienates Canada and Australia and India? These are the classic places that nobody alienates. Why do it? That’s the pathology that I see is most pernicious and most dangerous.

What should the United States do about it? Just try to be steady, and to recognize that leadership sometimes means you can’t do anything — you just have to be ready when the moment arises. And a moment will come.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.