magazine text block

What has been happening in Hong Kong these past few years has not surprised me. I still remember with perfect vividness gazing out my hotel on July 1, 1997, looking down on the parade ground dock where the Britannia was berthed as torrential rain fell and the British Union Jack was lowered for the final time. The Prince of Wales was in military whites and Chris Patten, the last British governor, looked on lugubriously as he waved goodbye and boarded the Britannia to leave this Crown Colony to the People’s Republic of China.

Under Deng Xiaoping’s creative “one country, two systems” formula, the people of Hong Kong had been promised a “high degree of autonomy” for 50 years. But as the Britannia steamed out into Hong Kong Harbor and the night sky erupted in a spectacular array of fireworks, I felt far from certain that the next half century would hew so neatly to Deng’s very pragmatic and reasonable roadmap. Two factors left me skeptical. First, having studied Chinese history for many decades and been in and out of the PRC many times a year since 1975 — when Mao still ruled and the Cultural Revolution still raged — I knew how sensitive issues related to colonialism, imperialism, and territorial sovereignty were for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). After all, since its founding in 1921, the Party had woven an elaborate tapestry of grievance against just such foreign predations. Moreover, I also knew how deeply, if surreptitiously, Beijing had been involved in Hong Kong life even when it was under British administration. If the CCP was anything it was well organized, tenacious, took umbrage easily at any criticism or slur, and was always inclined to retaliate, sooner or later, when it felt itself wronged.

I had participated in endless panels in Hong Kong before the handover, in which I invariably expressed doubts that Beijing would be able to keep its hands off of the former colony for a full 50 years, much less ever actually allow it to elect its own chief executive and legislative council by direct popular vote. What I had not expected was that Hong Kong, as a special administrative region of China, would be able to maintain as much independence as it had for as long as it did — 23 years — not quite half the time Deng had allotted for the process before a complete “return to the motherland’s” (回归祖国) control.

In writing the piece that follows for Newsweek before the handover, I was trying to divine the future of Hong Kong under Deng’s very unusual arrangement by using history as a way to look at how China had treated its other great treaty port, Shanghai — which with its “foreign concessions” had been a quasi-colony — upon taking it over in 1949. Steeped in a Leninist ideology that had long made it deeply neuralgic about any situation in which it had less than complete political control, especially under circumstances where foreigners might be involved, I could not imagine that the Party would long be able to resist interfering in Hong Kong’s affairs. After all, its free press, public protests, and open universities were viewed as patent insults to one-party control. And, just as in Shanghai in the 1940s, the Party already had a substantial underground network in Hong Kong that made responding to such insults all the more irresistible. With two such different political systems in collision, it seemed a foregone conclusion that at some point the Party would feel the call to react when challenged. And now, it has.

“One country, two systems” was a nice dream we were all allowed to dream that rainy night in 1997 as the Union Jack came down over Hong Kong for the final time. Alas, it was a dream allowed a much shorter life span than Deng and British negotiators had set forth when they signed the Sino-British Joint Declaration in 1984.

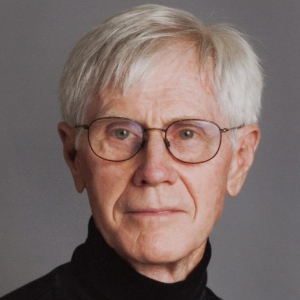

British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and Chinese Premier Zhao Ziyang exchange documents in Beijing during the signing of the Sino-British Joint Declaration on December 19, 1984 as Deng Xiaoping and others look on.

Peter Jordan/Alamy

magazine text block

The Hidden Hand

by ORVILLE SCHELL

July 7, 1997

This story written was originally published by Newsweek. Reprinted with permission.

Analogies between Shanghai's "liberation" in 1949 and Hong Kong's "return to the motherland" this July are not perfect, but the Shanghai precedent does have an intriguing historical resonance. Hong Kong and Shanghai were both "treaty ports," born of the Opium Wars and ultimately de-colonialized and integrated into the People's Republic of China. Although Shanghai was not an outright colony like Hong Kong, its heart was its waiguo zujie, or "foreign concessions." These were governed "extraterritorially" by Western powers, meaning that Chinese law and China's constabulary exercised no jurisdiction there. Shanghai's special status (along with that of 14 other treaty ports) ended in 1945, thus concluding one of modern China's deepest humiliations. When the People's Liberation Army (PLA) marched in and "liberated" Shanghai in 1949, the Chinese Communist Party completed the process of expunging foreign control and influence from this once cosmopolitan, if decadent, city.

Almost 50 years later the Communist Party does not dare speak of "liberating" Hong Kong. But the same nationalist sentiment that made Shanghai's transformation such an emotional watershed for ethnic Chinese now animates the huigui, or "return" of Hong Kong to Chinese sovereignty. Just as in the case of Shanghai, the transition will be marked by the PLA's highly symbolic entrance into the city. The bulk of the elite, 10,000-man "joint force" from the Chinese Army, Navy and Air Force has been recruited from what one official source describes as "remote farming communities" of Shandong province, whose people are known for their naiveté and obedience.

China and Britain worked out the basic procedures for the handover during 15 years of formal negotiations. But to help assure its grip on Hong Kong, Beijing also has engaged in secret dixia gongzuo, or "underground work," at which it became skilled while struggling against the Nationalist government and the Japanese occupation forces earlier in the century. That it often involves duplicitousness and ruthlessness goes without saying. After all, as Leon Trotsky noted, "we do not enter the kingdom of socialism with white gloves on a polished floor."

Indeed, underground efforts in Hong Kong are strikingly reminiscent of the party's campaign to secretly organize key sectors of Shanghai before 1949. There, an elaborate network of underground xiaozu, or "party cells," infiltrated labor unions, universities, factories, civil service and even customs bureaus, essentially giving the Communists de facto control of the city before the PLA ever entered. The Shanghai municipal police force was perhaps the most important target. The Communists began recruiting young police candidates in January 1949, according to Frederic Wakeman, a University of California, Berkeley, scholar who has been researching the transition. Special police training camps were established in Shandong province, the same area from which many troops in today's Hong Kong garrison were drafted.

When the Nationalist police chief in Shanghai finally fled to Taiwan, he instructed his deputy to stay behind and mobilize resistance to the Communists. However, it turned out that the deputy was a clandestine Communist. When PLA cadres moved in to the Fuzhou Road headquarters of the Shanghai police, "the entire police force's commandants were outside with keys to the station and all of the material needed for the new government to take over," says Wakeman. "You can be sure there are many [Beijing agents] in the Hong Kong police force right now."

Mainland agents have also been operating out of the New China News Agency (Beijing's unofficial embassy in Hong Kong, with a staff of more than 500) and from state-owned Chinese enterprises. Mainland companies, such as the China Resources trading firm, have been assigned to provide cover for party operatives. The Hong Kong magazine Meng Ming reported in April that Beijing recently appropriated some $150 million to set up front companies as potential cover for 900 new emissaries to be infiltrated into the colony before July 1.

To date, the Chinese Communist Party has had no official, aboveground presence in Hong Kong. Nonetheless, it is reported to have upward of 8,000 members coordinated by the Hong Kong-Macau Work Committee at the New China News Agency. Last March, legislator member Christine Loh decried "the official silence" about the party's existence. She pointed out that if the party operated as a parallel structure to the government, as it does in China, it would be "fundamentally subversive to our way of life" and "disastrous for Hong Kong." When Loh sought a formal "clarification" of the party's future status and role, however, her motion was defeated — by one vote.

Like watching mountains slowly emerge from the mist, we have begun to see hints of how widespread China's underground networking efforts have been. The case of Immigration Department chief Lawrence Leung highlights how difficult it may be for Hong Kong officials to maintain independence as Beijing steps up the pressure. Appointed in 1989, Leung was key in carrying out a British plan to offer 50,000 British passports to prominent Hong Kong Chinese as "insurance" against the uncertain future of the colony. But since Leung abruptly resigned last July, rumors have circulated that he was fired for behind-the-scenes contacts with Chinese officials. Chief Secretary Anson Chan refused legislators' demands that she reveal the reasons for Leung's resignation, claiming that it would be "injurious to the public interest."

Before sailing off on the Britannia, Gov. Chris Patten himself also made a rare allusion to the party's underground presence. "I guess that part of the reality of life in Hong Kong for the best part of 50 years has been that there are Communists in Hong Kong operating in the way in which Communists customarily operate, underground and in cells and through united front operations," Patten told legislators. But he added that he had refused to lead a "witch hunt" against the Communists. "I think part of the stability of Hong Kong is that we know when to close one eye," Patten said.

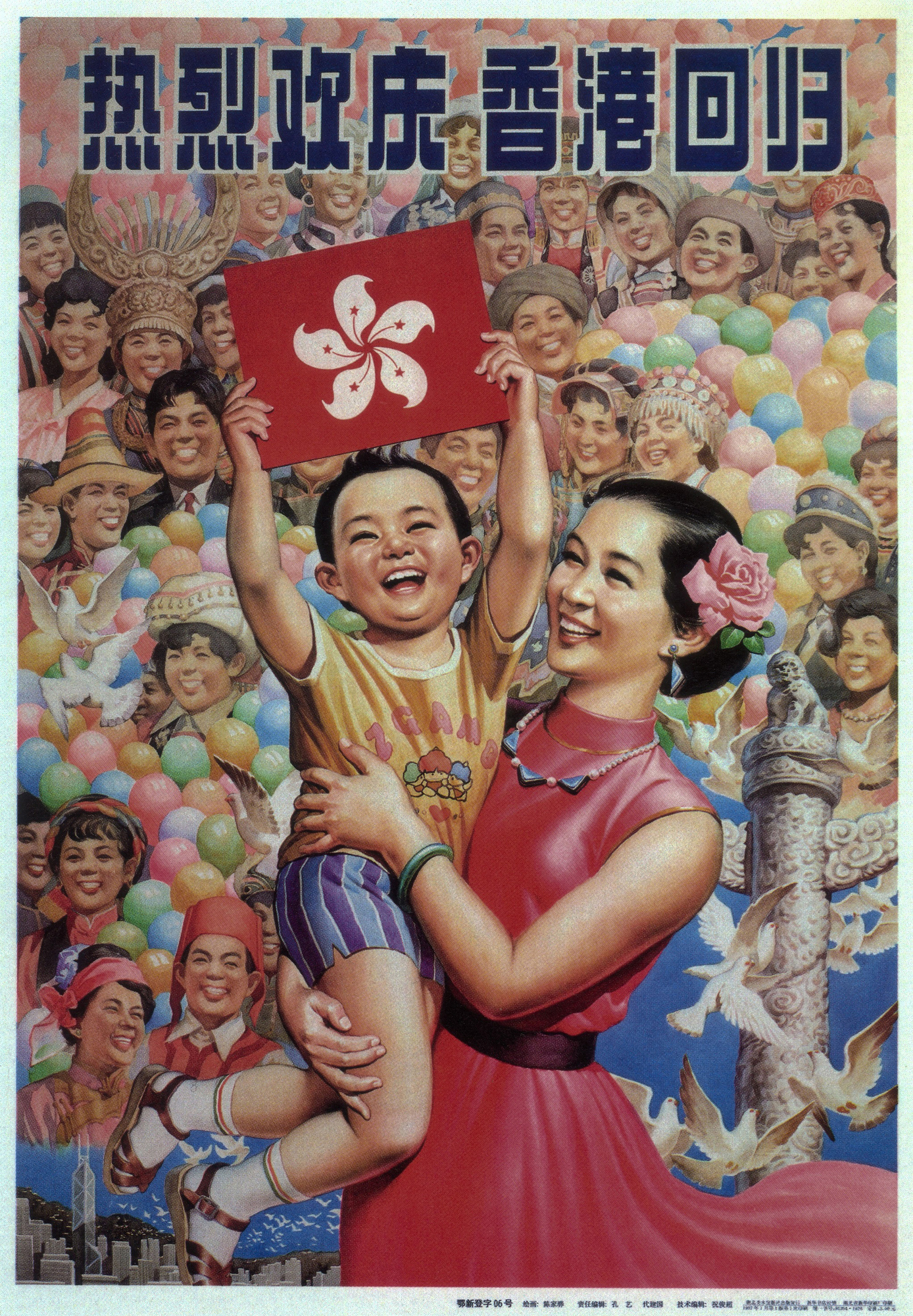

A young girl in Hong Kong celebrates the handover on June 30, 1997.

Richard Baker/Alamy

magazine text block

China also has made considerable efforts to gao guanxi, or "create a network of relationships," between its security ministries and Hong Kong's crime rings and secret societies. The party's affinity with underworld organizations comes straight from Maoist doctrine. In a 1936 appeal to the Gelaohui, the Society of Brothers and Elders, Mao declared that "the treatment inflicted on the Gelaohui by the ruling class is really identical with that inflicted on us ... You support striking at the rich and helping the poor; we support striking at the local bullies and dividing up the land ... Our views and your positions are, therefore, quite close."

It is doubtful that Jiang Zemin's crypto-capitalist Communist Party feels real proletarian solidarity with criminal triads. But like Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek, who won Shanghai in 1927 by forming an alliance with the city's notorious Green Gang (and then massacring the Communists), the party wants to be on the right side of the underworld as it tries to keep order in its new territory. After all, Hong Kong is reputed to have some 50-odd active triad groups — including the Sun Yee On, which has up to 50,000 members and is even said to include some senior officials in its ranks.

In a move that was sublimely practical but also stunningly cynical, Chinese Minister of Public Security Tao Siju made an arresting public admission in April 1993. At the very time that Hong Kong government officials were engaged in an all-out international effort to control triad ventures involving drugs, prostitution, blackmail and murder for hire, Tao told a Beijing news conference that the Chinese government was willing to ally itself with secret society leaders as long as they were "patriotic and concerned with the stability and prosperity of Hong Kong," In fact, boasted Tao, Beijing had already consummated this unholy alliance by allowing a group of 800 triads to serve as voluntary bodyguards for an unnamed party leader while he was making a certain overseas visit.

It may be that as China's underground efforts are revealed, Hong Kong will look less like a "special administrative region" with a "high degree of autonomy" and more like China itself. Deng Xiaoping's notion of "one country, two systems" may ironically still apply, but not in the sense that Hong Kong's systems will remain separate and distinct from those of China. After all, China is already a country with two systems — one for its increasingly laissez-faire economy and the other for its refractory Leninist political system. When all is said and done, this may be the "one country, two systems" model that Hong Kong is forced to adopt.