magazine text block

Few people have devoted more time to understanding the U.S.-China relationship than Orville Schell. He is the Arthur Ross Director of the Center on U.S.-China Relations at Asia Society and the author of more than a dozen books. Since the 1970s, Schell has been visiting and observing China as a journalist and scholar, meeting its leaders in politics, business, academia, and the arts. Schell is also the co-chair of the Task Force on U.S.-China Policy, a group of scholars and diplomats whose most recent publication in 2019 made the case for a new “smart competition” in U.S. policy toward China.

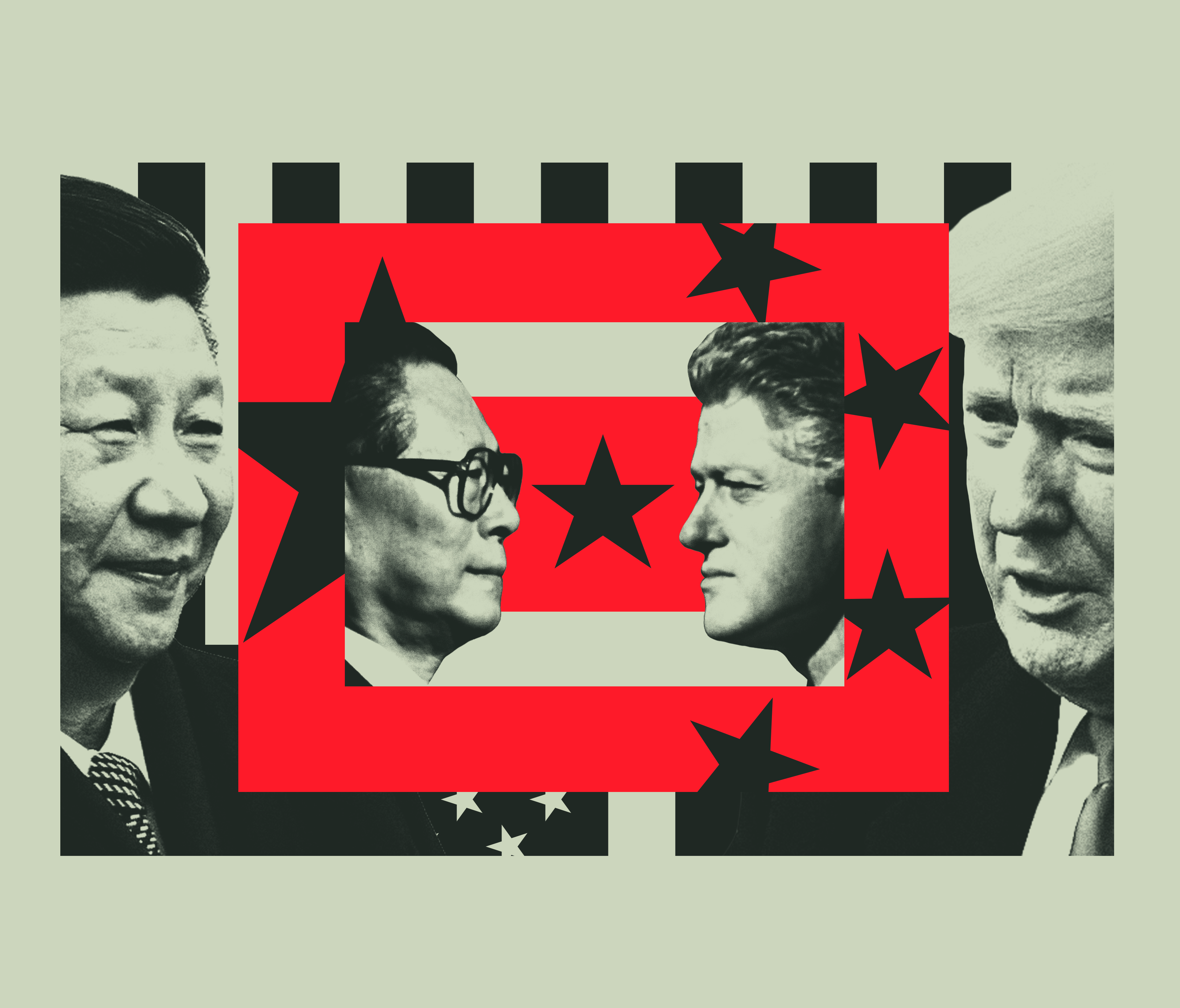

Schell sat down with Asia Society Executive Vice President Tom Nagorski to talk about the last 20 years of U.S.-China relations, viewed through the prism of two presidential summits: The meetings that U.S. President Bill Clinton held with Chinese President Jiang Zemin in 1998, and the 2017 visit of President Donald Trump with Chinese leader Xi Jinping. As Schell explains, the differences between these two events speak volumes about the changes in both countries, and in the U.S.-China relationship, over the past two decades. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

TOM NAGORSKI: Before we get to these two specific events and take a little time travel back to 1998, you said recently that the big picture U.S.-China relationship in this time frame goes something like this: the birth of the policy of engagement, the evolution of that policy, and more recently the death of that policy. That’s a stark statement and analysis. How would you characterize where things stood in terms of the utility of engagement as perceived by both sides?

ORVILLE SCHELL: What was interesting about 1998, when Clinton went to China to visit Jiang Zemin, was that it was less than a decade after 1989 and the Beijing massacre, when we really thought the U.S.-China relationship would fall apart — and it didn’t.

There were two reasons for that. One was Deng Xiaoping — he revived economic reform if not political reform in 1992 — and the other was that Jiang Zemin was a strangely warm Chinese leader. And what I mean by warm is he had a sense of humor. He was a bit of a clown. He was quite affable and he really did want to contend as a normal leader in the cosmopolitan world.

When Clinton came to China, remember, he had just done a somersault. He had come into office speaking about the “butchers from Baghdad to Beijing.” And yet he had come around to the notion that it was better to work with China than to eschew them and push them aside. (He gave them permanent most-favored-nation trading status and let them into the World Trade Organization.) So he shows up in Beijing, and, quite counterintuitively, these two countries which had almost shipwrecked after 1989, had a rather warm and open relationship particularly between the two leaders.

Jiang Zemin is ushered by Bill Clinton to a state dinner at the White House in October 1997.

Luc Novovitch/Alamy

magazine text block

You’ve been sort of a Zelig-like figure at all these occasions — watching them arrive at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing. You wrote at the time that the two leaders had effectively decided they want to let bygones be bygones. Was that a Tiananmen Square reference?

Yes. Tiananmen Square was a giant obstruction to everybody’s ability to feel comfortable with each other. And yet in that summit they met in the Great Hall of the People at Tiananmen Square after a big honor guard greeting outside Tiananmen Square. And, quite extraordinarily, Jiang Zemin decided at the very last minute that the press conference, which would have an open question and answer period with the media from all over the world, would be broadcast live on radio and television. This is something that would be unimaginable today.

And was unimaginable then.

It was not unimaginable but it was quite a bold move by Jiang. I think what he was trying to demonstrate was that China was slowly opening and wanted to become more digestible in the world as it was constructed outside of China. He didn’t want to be a big leader, a cold war dictator. And what proceeded was the most extraordinary press conference I think I’ve ever been to in China. These two leaders in a very affable, friendly manner began to talk about subjects which had long been considered far too sensitive for such a discourse.

As you say, it was unheard of at the time. No chance for the Chinese censors to do anything because it’s going out there. Clinton tells Jiang Zemin in the hall there that the use of force and loss of life at Tiananmen were “wrong.” That freedom of speech and association are the rights of people everywhere. What was it like to sit there and listen to this going out live?

Well, to Jiang Zemin’s credit he grinned through it, he replied. He stood up and said we have different systems, different values et cetera, et cetera. And he went right on.

It seems to me that it was such a rare moment — when a leader didn’t get so offended that he pulled out the humiliation card, the face card, and bring the whole press conference down around everyone’s ears. That’s exactly the kind of flexibility that allows things to work out even when there are profound disagreements that we miss today. That would be considered a slight to the throne of the most grievous order now for a U.S. president to comport himself in this way. I think Xi Jinping wouldn’t even allow an opportunity for such an occasion to arise.

magazine quote block

magazine text block

You mentioned Jiang Zemin’s reply. As you say, he took it well and then gave right back. He said they could not have enjoyed the stability they enjoyed then had they not used force at Tiananmen. Again, this was an open conversation. They had a similar exchange about the Dalai Lama. I think President Clinton said, “I know the Dalai Lama. I think you should get to know him you’d like him.”

Yes. It was astounding! And actually it was Jiang Zemin who raised the question of Tibet himself, which was unthinkable. He asked Clinton why are Americans so fascinated with what he called “Lama-ism,” which was Tibetan Buddhism. And he was grinning the whole time and Clinton took that as an invitation to pop right off and say how much he liked the Dalai Lama. So this was pretty extraordinary moment.

Back then, a lot of people thought Jiang Zemin was a bit clownish. He loved to sing “Home On the Range.” He’d recite “The Gettysburg Address.” Everybody thought of this guy as, really, not very ready for prime time. But looking back on him, I realized that there was something quite amazing about this man. He wanted China to become soluble in the world. He didn’t want China to be isolated, separate. And he didn’t wear his pride on his sleeve.

So what you’ve described, whether it’s clear thinking at the moment as a reporter or your reflections 20-some years on, sounds like a profound positive moment for engagement between the two countries. Did it bear fruit in the years immediately after?

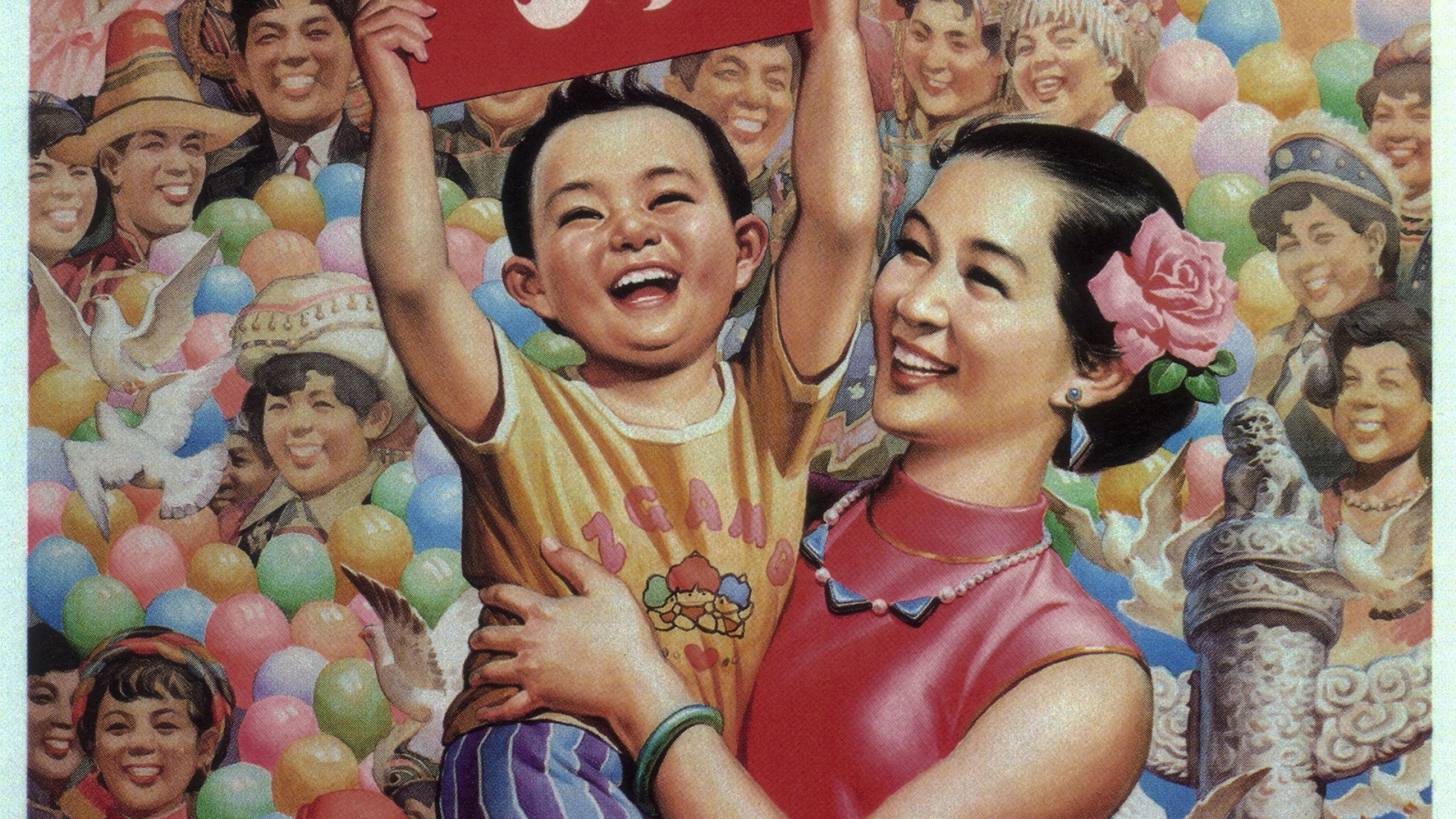

Of course, China profited immensely from being in the World Trade Organization and having most-favored-nation trading status. In a certain sense, it helped precipitate the China economic miracle. But then Jiang Zemin left office and Hu Jintao came in and Hu Jintao was sort of a gray, blurry, unclear leader. He lacked a certain confidence, certainly in the stylistic bravado, or interest in really getting out in the world and mixing it up. He was much more retiring and reluctant and it became a little bit unclear whether China really wanted to join in with the world, as Jiang Zemin evidently did.

Donald Trump with Xi Jinping at a cultural performance at the Great Hall of the People in November 2017 in Beijing.

White House Photo

magazine text block

Before we leave Jiang and Clinton, it’s worth noting that Clinton quite famously predicted after that summit that China would go the way of the regimes in Eastern Europe. He said business engagement would open the country. He said “the spirit of liberty” would carry the day. “The genie of freedom will not go back in the bottle” was the oft-quoted line of the day. What happened to that genie of freedom?

So this is when it got branded as engagement. Clinton called it “comprehensive engagement” and the theory was that if you trade and interact, China will become less indigestible and more willing to join the global order and the rules of the game as they exist.

And he wasn’t the only one to believe that.

No, no. Everybody believed it. What happened was engagement used to be presupposed on opposing the Soviet Union. Then, when the Soviet Union fell apart, engagement lost its logic. So Clinton reinstalled a new operating system for engagement, built around the supposition that with more trade and interaction, history is on our side. Remember when Clinton told Jiang Zemin: “You’re on the wrong side of history”?

That was the faith. I think in retrospect it was a bit naïve, but actually it was an exercise of American leadership too — to think that you could wisely help shape and guide China as it emerged from this very intense revolutionary Leninist experience. I think it was a gamble worth taking.

So 20 years later, I think it’s just plain interesting to look at what was on the agenda then and what’s on the agenda now — which says as much about the times as it does probably about the relationship. In 1998, you had human rights, Tibet, you had missile proliferation, and then, of course, China about to join the WTO. On international security issues, you had India-Pakistan front and center on the agenda.

Two decades later Trump comes to Beijing and meets Xi and there it’s trade, trade, trade, right? Allegations of unfair trade, currency issues, and some issues that really weren’t in the ether or in the vocabulary back then: cyber theft, AI, 5G.

And don’t forget the South China Sea and Taiwan are heating up, and now Hong Kong and North Korea.

Deng Xiaoping and Jimmy Carter in the Oval Office during a nine-day state visit in 1979.

Keystone Press

magazine text block

Whatever the engagement policy was, to what extent does an utterly different agenda for the two countries change things? Or is that a red herring in this discussion?

The thing about the Jiang Zemin era — their slogans were: “peaceful development,” “peaceful rise,” and “keep your head down and bide your time.” In other words, don’t do anything muscular. Don’t be thumping your chest. Don’t be going around the world making trouble and scaring people.

What changed with Xi Jinping was that he came in after the economic crisis of 2008 and `09. He came in not being a sophisticated cosmopolitan person: doesn’t speak any foreign language, never studied abroad, never had experience abroad. He’s very much a home-grown leader, right? I think he thought, “Aha. There’s American decline happening at the same time we’re rising!” He is having his “China Dream.” And what was that? The rejuvenation of China. China’s new restoration as a great power with wealth and power at its disposal.

I think he was sort of deceived a bit by a combination of things into thinking, “Well, maybe the moment has come for China to stick its head up and not bide its time.”

There’s an expression in Chinese, the zhongguo fangan (中国方案), which means the “China option.” Xi possibly had begun to think, “Maybe China discovered the way to develop for itself and possibly even other countries?” It had done so well. So, there was a bit of overweening ambition, maybe arrogance about China’s possibility of being on the verge of becoming the ascendant power. From there on we began to unravel the notion that we could converge; that collaboration, cooperation, and trade were a solvent for our differences.

We began to find the differences becoming more exaggerated and China less and less agreeable and willing to give a little and get a little, play by the existing rules of the trade system in the world order in order to develop and get ahead. That was the beginning, the first shot fired into the bow of engagement.

Mao Zedong shakes hands with Richard Nixon during his historic 1972 trip to Beijing.

Keystone Press/Tango Images/Alamy

magazine text block

OK. So Donald Trump comes to the same setting. November 2017. It’s been one year since his election and Xi Jinping at this point is about halfway through — assuming it’s going to be a 10 year tenure (and I guess it’s another conversation). But he’s five years in. And, I guess the point you’re making here is that Donald Trump is coming not only to a totally different China in terms of its strength and its economic growth — they’re about to catch us — but also in terms of its confidence as a nation. To what extent does this change the dynamic?

Part of the “China Dream” is that China should no longer apologize for who it is. Now it imagined that it had the resources and the military power to throw its weight around a little and it didn’t see any reason to be so accommodating to the global order as it existed because it didn’t feel it needed to. But the problem was that the U.S.-China relationship depended on a certain flexibility.

It depended on this notion that somehow we were heading in the same direction — at least in certain ways — that reassured people that it was worthwhile keeping on trading and interacting. And I think one of the major catalytic elements in this change was the tensions created by China’s claims in the South China Sea. China under Hu Jintao and then under Xi Jinping, decided this is a “core interest,” or in Chinese, hexin liyi (核心利益). When it comes to “core interests,” the Party does not negotiate. What are the “core interests”? Taiwan, Hong Kong, Tibet, Xinjiang. Basically what core interest implies is: This is ours. There will be no discussion.

We can discuss other things.

Yes. Other things, but not this “core issue.” So that just threw a giant wrench in the works because the South China Sea goes all the way down to Indonesia and China basically was declaring what was inside that so-called “nine-dash line” as their own territory.

Now, just to push back a little bit: Donald Trump didn’t come in November 2017 hollering, at least not publicly, about the South China Sea or about Taiwan or certainly not about Xinjiang.

Well, he wanted to make a phone call to Taiwan.

Correct. But fair to say that most of what Donald Trump came to talk about and fulminate about were these economic issues and to some extent tech issues. To play devil’s advocate here — why not come with the posture that “OK, China has advanced remarkably since Bill Clinton was here. China is on a par almost with the United States in terms of its economic place and stature on the globe. And we should come recognizing that. And it is fair for them to feel that they’re not to be pushed around anymore.”

I think Trump’s assumption — which grew out of people like Steve Bannon, Peter Navarro, and Robert Lighthizer — was that the U.S. had been taken. The playing field wasn’t level, and the U.S. national interest was being violated repeatedly, whether it’s in trade or cybersecurity — you name it. The change had already begun under Obama with the so-called “pivot to Asia,” which was a recognition that things were out of balance and had to be put back in balance or the engagement policy that we’d been adopting for decades wouldn’t function. So when Trump came in, he was really the first person to say, “Engagement is dysfunctional for American interests.”

magazine text block

OK. Tons have changed as we’ve discussed in terms of the issues, but what about just the plain old summitry and atmospherics that November in Beijing?

Well it was very claustrophobic. There was very little meaningful exchange. One thing I will say to Trump’s credit was that even as he turned up the heat in terms of hostility toward China on trade and other things, he kept the relationship with Xi, the personal relationship, open. Trump kept saying “He’s my friend we get along fine. He’s great.” But if you watch the two interact, you saw none of the élan and the excitement and actually the real pleasure that you could see with Clinton and Jiang Zemin, or Deng Xiaoping and Jimmy Carter or even Mao Zedong and Richard Nixon. It was very ritualistic with Xi. Very cool. Frozen in a certain ceremonial aspic.

These things matter, right? I mean going back to Soviet summits. My gosh, acres of newsprint were spent on those kind of atmospheric questions. And when you talk about the United States and China, these things matter, right?

This is where leadership plays a key role and such things suggest the temper of a leader in terms of wanting to bond and work things out. It gives a reading of whether they can do it or not, or whether they’re being pushed or played or obstructed or whatever. There was none of that in evidence beyond the ceremonial aspect when Trump met Xi.

Is it too simplistic then to look at Trump and Xi in 2017 and see on the one hand a Chinese leader who’s feeling strong, confident —

— but strength and confidence built on a profound sense of weakness, which is often the worst kind of confidence because it manifests itself as hubris; it’s not strength at all.

magazine monotony

magazine text block

And here is an American president who for the first time maybe in modern history is going to go full bore with the points made as a candidate about attacking China on points X, Y, and Z. Do you have a misreading on both sides? It’s a recipe for something not great. Which I guess is where we are now.

I think there are tragic flaws on both sides. The tragic flaw on China’s side is the inability to recognize how much is at stake, that flexibility is at the heart of good diplomacy, and that national interest is often served by making compromises. The tragedy on Trump’s side is not that he’s misidentified Chinese intentions or the fact that the playing field was grossly out of level, unreciprocal, and needed fixing. It was that he hasn’t got a clue, once you challenge the existing order, about how to put the thing back together again. What do you do when you decide engagement doesn’t work? What’s your policy? You challenge them and then what?

You’ve had a whole paper recently that argues for what I think you call “smart competition” between the two countries. Not smart engagement, but smart competition. Our colleague Kevin Rudd, former prime minister of Australia who runs our policy institute here, has spoken and written about what he calls the “avoidable war.” Those both in their own ways are roadmaps for some greater engagement. What’s the remedy here?

I think here is where leadership is so important. When you have two countries that have such demonstrably different and contradictory political systems and value systems, if you don’t have good leadership — leaders who can say, “All right, we’ll cooperate here, we’ll compete here, but we will not go to war there” — then you have a very dire situation.

What I fear now is neither of our leaders are capable of putting the relationship back together in a new format which embraces China’s rise and the different systems and values, while keeping the peace in critical areas. This requires both sides to be flexible. But China, by declaring so many “core interests,” denies itself the flexibility to be able to make accommodations.

Finally, let me just say — and you know I’m a stern critic of my own country — over the last seven presidential administrations each U.S. president has bent over backwards to find some accommodation in very trying circumstances. Trump, not so much. But Trump’s virtue is he recognized the situation was unsustainable and out of balance.

Hunting for some silver linings here, do you see any areas where at least some accommodations could be made that would at least lower the temperature a little bit?

Well, antiterrorism was one area but unfortunately because of the Uighur situation in Xinjiang, and China’s posture toward Muslims, it has been very difficult to effect any kind of a partnership here. The antinuclear question with North Korea had some promise because China didn’t want to see a nuclear North Korea. But, even that has eroded.

I do think climate change is the biggest and most obvious challenge. It’s just that the U.S. doesn’t recognize it now. But China is missing an opportunity to play an even greater leadership role in this area if it chose to do so. Short of that, I just do not see what the new Soviet Union is that could bring us together.

I suppose on the climate point, not to prognosticate too much here on the American political front, but we could have a new leader of course and that climate thing could come back into play as some mortar for the bridge building of the U.S.-China relationship.

It could, Tom, and I think we have to remember that we have been at impasses like this several times before. 1989 was one. 1979 was one. 1972 was another. And we did manage to break through.

We’re in a situation now where the leaders seem to be losing the capacity to find that new, paradigm-shifting common ground, and that’s what’s so alarming. Engagement was an astounding policy because it lasted for so long and everybody bought into it in one way or another.

Reaching here for one more stab at a silver lining. We’ve been looking at two summits 20 years apart. Let’s say we have a 2040 summit — a couple of leaders in the U.S. and China whose names we probably don’t know right now — what’s a headline on the good side of the ledger that you could see written that might make us or our children feel a little better?

If we could avoid some problems in the South China Sea, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, then we may be able to elide through this period of tension to a place where we would find some other cause to join forces.

If I were Trump and I were Xi Jinping, I think the only thing that’s left to do now is if each would appoint some trusted plenipotentiary to set up a very small team on each side to look at alternative scenarios on an emergency basis. Take two weeks, then get together for a week with the two teams and compare roadmaps, see if there’s anything we can agree on, any off ramps to the collapse in the relationship.

Short of that I think the signs don’t leave me filled with much optimism.