magazine text block

When China’s savvy and energetic foreign minister Wang Yi set off in late May for a tour of eight Pacific Island states, he had reason to feel confident about China’s place in the region.

Beijing has invested in aid and infrastructure projects in the Pacific and prioritized agriculture, fishing, health, and tourism cooperation. Trade between China and Pacific nations is growing at 13% a year, according to Chinese data. And in March, Beijing inked a controversial agreement with Solomon Islands that opened the possibility of Chinese security forces being deployed there. Two years earlier, China had persuaded both Solomon Islands and Kiribati to switch their diplomatic recognition to China from Taiwan.

On his May trip, Wang had an even bigger prize in mind — a joint agreement covering a host of security, economic, and environmental issues with the 10 Pacific Island countries that recognize China. But though he managed to sign a slew of bilateral agreements, Wang returned to Beijing empty-handed on the region-wide framework. Instead, China received the kind of frank feedback it might normally expect only from its most powerful competitors.

The President of the Federated States of Micronesia wrote to his fellow Pacific leaders warning that China’s proposed agreement was designed to bind Pacific nations “very close into Beijing’s orbit.” The Prime Minister of Fiji told Wang the region needed “genuine partners, not superpowers that are super-focused on power.” And the secretary general of the Pacific Islands Forum urged China to “nurture a relationship that is respectful of … our regional mechanisms.”

Beijing won’t give up its goal of a more China-centered Pacific easily — its diplomats are already touting a revised version of the framework. But the unusually sharp response to Wang’s proposal reflects growing discomfort with the tide of China-U.S. rivalry that now surges through the region. Pacific leaders don’t want to be squeezed by a major power competition or railroaded into invidious choices. Wang’s proposal was also seen as a risk to the centrality and unity of the Pacific Islands Forum at a time when it has been rocked by internal division (most recently by the withdrawal of Kiribati).

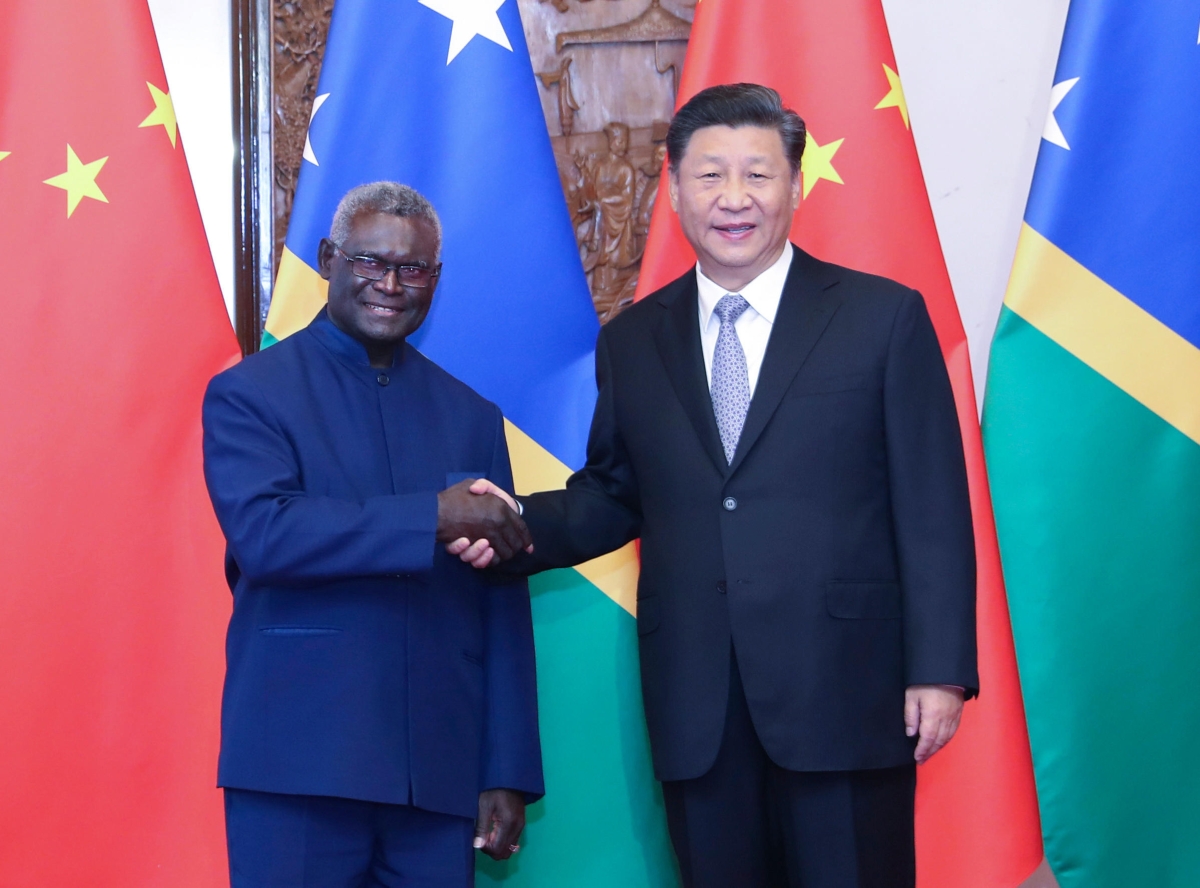

Xi Jinping and Manasseh Sogavare

Chinese President Xi Jinping, right, meets with Solomon Islands' Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare at the Diaoyutai State Guesthouse in Beijing, China, on Oct. 9, 2019.

Yao Dawei/Xinhua/Alamy

magazine text block

What’s at stake

At first glance, the remote western Pacific might seem an unlikely setting for a China-U.S. tug-of-war. Papua New Guinea aside, the collective GDP of Pacific Island states weighed in at less than $10 billion in 2021. Small populations are scattered across impossibly vast distances of water. In their own telling, Pacific Island countries are “large ocean” nations, custodians of a “blue continent” comprising nearly 20% of the earth’s surface.

But China is determined to build influence across the Global South as ballast in its ever-deepening competition with the United States. Beijing’s top priority is its long, see-sawing battle to poach Taiwan’s Pacific diplomatic allies. The support of Pacific island states in other contested arenas, like the United Nations, on issues such as human rights, Xinjiang, and Hong Kong also matters to Beijing. Then there are economic interests, especially fishing, timber, and tourism.

The United States now finds itself having to address long years of relative neglect. U.S. interests are largely defined by China’s gains. Washington wants to preserve international space for Taiwan, support democracy and good governance, and protect the resilience and autonomy of Pacific states as China’s influence grows.

The U.S. also wants unhindered military access throughout the Pacific. The Biden administration worries that China seeks a base or other foothold for the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) in the region, in part to break free from what Beijing sees as the constraining presence of U.S. and allied forces elsewhere in the Pacific. Beijing’s security agreement with Solomon Islands might one day provide the opening China wants. A leaked draft suggests it cracks the door for PLA navy stop-overs and logistical replenishment. Solomon Islands leaders vigorously deny any intent to allow a base, but under China’s civil-military integration doctrine, any commercial ports built by China in Solomon Islands would almost certainly be developed with military uses in mind.

The concerns from the U.S. and other traditional partner nations go beyond security cooperation: Official Chinese media outlets now have a significant presence in the Pacific, allowing pro-Beijing narratives to seep into the region; loans from China are adding to high levels of debt stress in some Pacific countries, such as Samoa and Tonga; and China is energetic in courting elites, dangling economic opportunity along with official visits, training, and other less scrupulous inducements. The switch to China from Taiwan in Solomon Islands, for instance, came with substantial cash payments to help prop up the pro-China government of Manasseh Sogavare. Despite saying the region is big enough for all comers, Beijing is a tough competitor, often seeking to elbow out other Pacific partners.

As China increases its presence, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan are responding — stepping up aid spending, infrastructure financing, and defense cooperation, and pledging to work more closely together. For the U.S., meanwhile, long-stalled negotiations on support for the three Micronesian countries that have compacts of free association (Palau, the Federated States of Micronesia, and the Marshall Islands) now have greater urgency.

American officials are also more frequently making the long trek from Washington to Pacific shores. In a first, President Joe Biden will host Pacific leaders later this month. And in virtual remarks to the Pacific Islands Forum on July 12, Vice President Kamala Harris pledged America’s “enduring commitment” while announcing new embassies, the return of Peace Corps volunteers to the region, and a boost in funding for economic development and ocean resilience.

Kamala Harris at Pacific Islands Forum

U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris speaks remotely during the Pacific Islands Forum at the Grand Pacific Hotel, in Suva, Fiji, on July 13, 2022.

Kirsty Needham/Reuters/Alamy

magazine text block

Regional priorities

Pacific nations often grumble that Washington’s new focus has only come because of China. The dominating dynamic of rivalry with China is hard for the United States to escape. But U.S. officials working on the Pacific recognize that America’s gains will be deeper and more sustainable if Washington is attentive to the region’s priorities.

Listening to the Pacific means recognizing that the region sees U.S.-China competition as an unhelpful distraction from graver challenges. Closed borders helped keep COVID-19 at bay through much of 2020 and 2021, but at significant economic cost. Now, as the Pacific re-opens, keeping the pandemic contained has become a daily battle and the path to recovery, especially for those countries reliant on tourism, is challenging.

Above all, however, it is climate change that Pacific leaders identify as “the single greatest threat facing” the region. Pacific leaders want developed countries to phase out coal and fossil fuels, keep global warming below 1.5 degrees, and boost financing for climate change adaptation.

Here, the Biden administration’s climate ambition is an advantage at a time when the credibility of China’s emissions reduction commitments is under challenge.

A deeper U.S. agenda in the Pacific forged around support for economic development, ocean health, protecting fisheries, and climate resilience will build positive influence. The Biden administration’s Indo-Pacific strategy already points in this direction. In an era where bigger countries and more dangerous regions inevitably divert attention and resources, the challenge now for the United States is to deliver. Consistency and sincerity will be the keys to success in the “blue continent.”