The Return of Red China

Foreign Affairs

The following is an excerpt of Kevin Rudd's op-ed originally published in Foreign Affairs.

In 1978, Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping announced that his country would make a break with the past. After decades of political purges, economic autarky, and suffocating social control under Mao Zedong, Deng began stabilizing Chinese politics, removing bans on private enterprise and foreign investment and giving individuals greater freedom in their daily lives. This switch, termed “reform and opening,” led to pragmatic policies that improved Beijing’s relations with the West and lifted hundreds of millions of Chinese people from poverty. Although China remained authoritarian, Deng shared power with other senior party leaders — unlike Mao. And when Deng left office, his successors continued down much the same path.

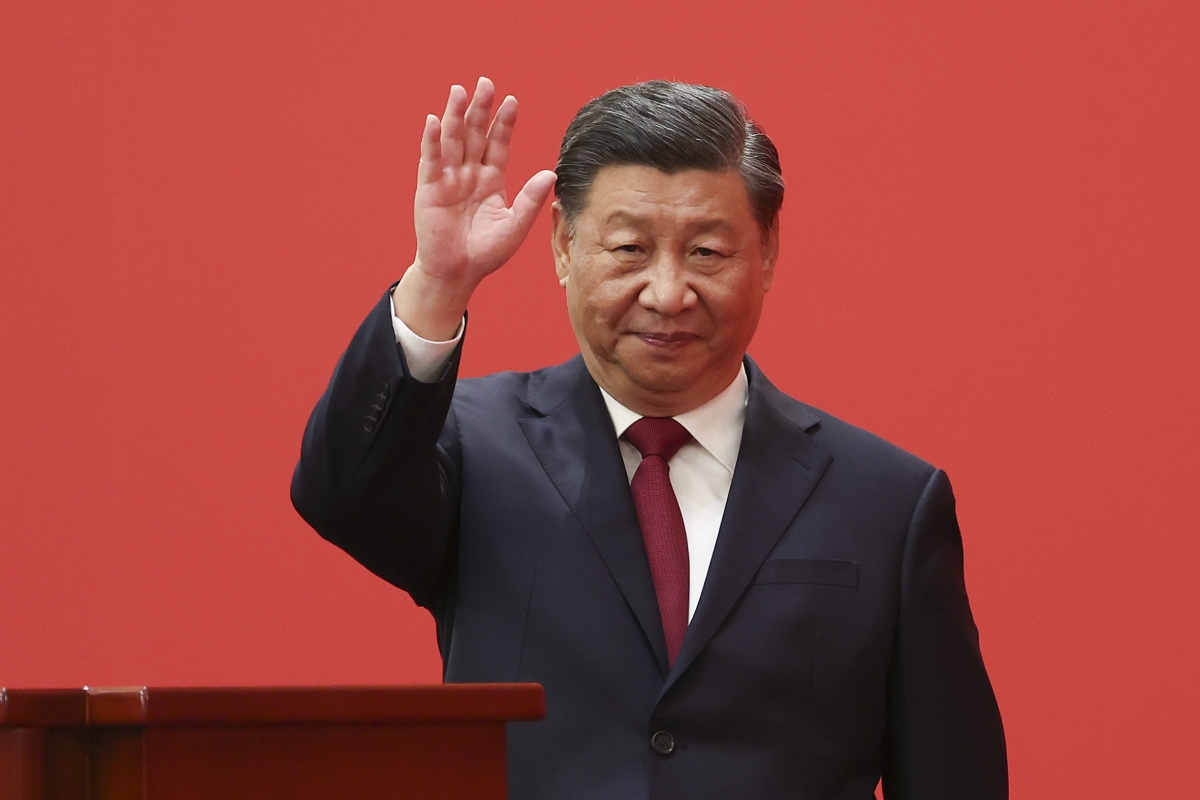

Until now. During the 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) last month, Chinese leader Xi Jinping brought the Deng era of Chinese politics to a definitive close. In many respects, it was clear that “reform and opening” was on its way out at the 19th Party Congress in 2017, when Xi proclaimed “a new era” in which the party would rectify the ideological, political, and policy “imbalances” left over from his predecessors. But it was the 20th Party Congress that gave Xi an unprecedented third term as leader and removed pro-market officials from the CCP’s leadership. It even removed Xi’s predecessor from the proceedings. After nearly 44 years, history will record that it was this congress that administered the last rites to Deng’s reformist era. The brave new statist world of Xi Jinping is now in full force.

That means foreigners must set aside the comfortable analytical frameworks many of them have used to analyze China for the last two generations. Most countries, including many in the West, are predisposed to think that when China’s leaders speak in ideological terms, it is not to be taken seriously (or that if it is, the ideology purely applies to the party’s domestic politics). But that is no longer the case. As I wrote in Foreign Affairs shortly before the party congress, “Under Xi, ideology drives policy more often than the other way around.” He is a true believer in Marxism-Leninism; his rise represents the return to the world stage of Ideological Man. This Marxist-Nationalist ideological framework drives Beijing’s return to party control over politics and society with contracting space for private dissent and personal freedoms. It also drives Beijing’s born-again statist approach to economic management, and its increasingly assertive foreign and security policies aimed at changing the international status quo.