The COVID New (Ab)Normal: America’s Place in the Middle East in a Post-COVID-19 World

Editor-in-Chief of The National, Mina Al-Oraibi

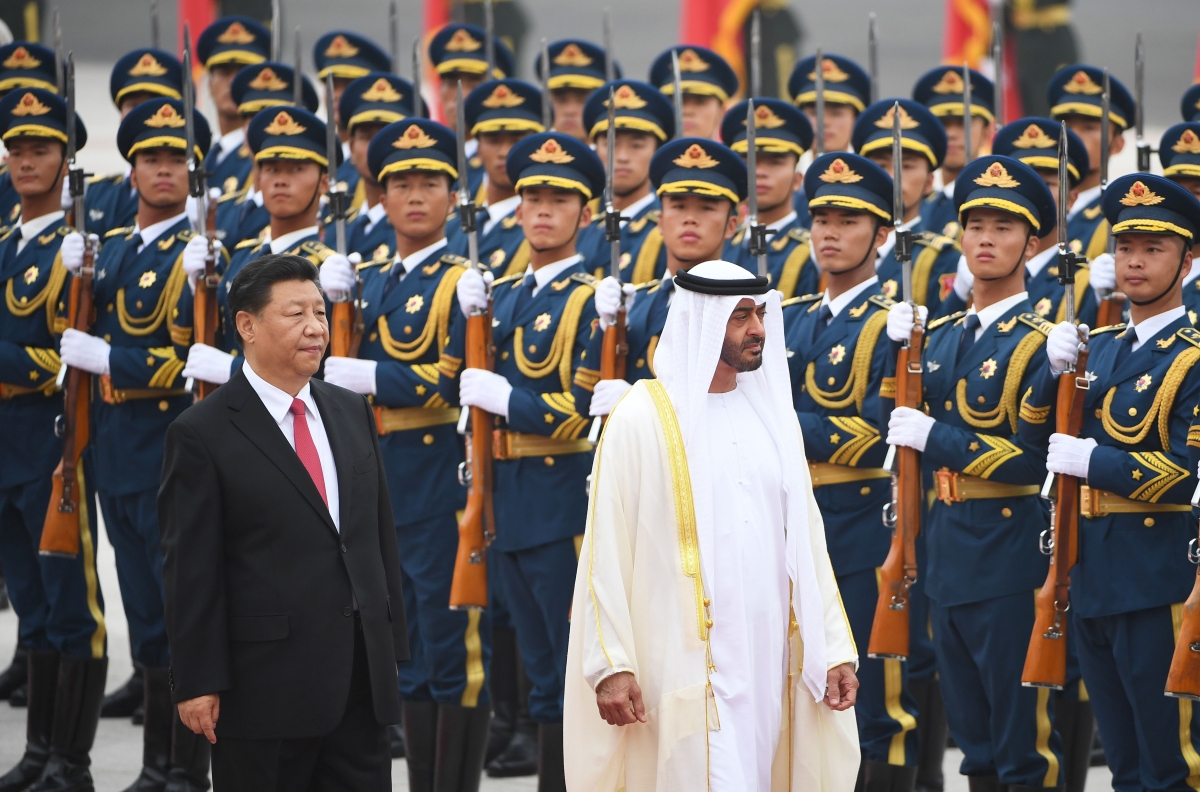

Abu Dhabi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan (C) reviews a military honour guard with Chinese President Xi Jinping during a welcome ceremony outside the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on July 22, 2019. (Greg Baker/AFP/Getty Images)

The political history of the 20th century in much of West Asia and North Africa can be told through a retelling of the consequences of great power rivalry. The carve up of the modern Middle East following World War I is a prime example of geopolitical competitions playing out on its territories. The signing of treaties created modern boundaries for the countries of the region with little regard for the people who lived within them. At the height of the Cold War, U.S.-Russian competition played out in the Arab world through military coups and the hijacking of national struggles as countries emerged from colonization.

After the demise of the Soviet Union, the United States emerged as the primary, if not sole, global power, creating the conditions for greater American influence in the region than ever before. This was further consolidated in the aftermath of the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990, leading to a global ‘coalition of the willing’ led by the United States that evicted Saddam Hussein’s forces from Kuwait but maintained American forces in the region. Yet at the start of the 21st century, America’s role in the region changed. In the aftermath of the September 11th attacks, the ‘forever war’ of Afghanistan followed by the 2003 invasion of Iraq, meant the United States was actively at war, and with it came a heavy financial and political cost.

Under the administrations of both Barack Obama and Donald Trump, there were public declarations and active efforts to disengage from the Middle East. The results of these efforts are mixed, however they have meant the United States is no longer the primary global actor in the region. Today, as the world battles the COVID-19 pandemic, the United States is also engaged in a game of competition with other powers, namely China and Russia. However, much of the Middle East does want not to pick sides, preferring to work with a number of countries, like China, on finding solutions. Twenty years ago this would have been unthinkable. COVID-19 has expedited a trend that was already gathering pace.

As the era of American dominance is coming to an end, the global role of China is of growing interest in the Middle East. American withdrawal from its leadership role in the region began under the Obama administration and was consolidated under the presidency of Donald Trump – despite the very different approach of each in this withdrawal. This was coupled with the United States announcing itself self-sufficient in energy needs, greatly reducing its reliance in the Arab world. On the other side of the world is China, keen to lead but in a different way. With its Belt and Road initiative (BRI), Beijing promoted a vision of interdependence reminiscent of times when trade routes came through the region. And although not all the countries of the region are within the specific plans of BRI, the logistical connections created by it impacts several countries in the region. China’s advancing of enhanced trade ties was underlined by an increase in oil imports from the Middle East’s oil-producers. In 2019, China’s oil imports from Saudi Arabia increased by 47 percent. In June 2020, China’s crude oil imports from Saudi Arabia rose 15 percent year on year. Furthermore, China’s handling of COVID-19, is seen as far superior than many Western liberal democracies, This has led to a greater appreciation of its capabilities, while the manner in which the United States federal government handled the pandemic is at best incompetent. All these developments are being watched and noted in the Middle East, especially as the COVID-19 crisis has further highlighted the importance of capacity to grow and adapt.

There are four primary drivers of regional relations with the two global powers. Firstly, economic ties, which include energy supplies. According to China Customs Statics, the trade volume between China and the Middle East increased to $294.4 billion in 2019, up from $227 billion the previous year. While Chinese oil imports continue to grow its influence in the Arab world, the singular role of the U.S. dollar ensures American influence is maintained. A number of currencies are pegged to the dollar, while others like Iraq and Lebanon rely heavily on the dollar for their economic activities.

Secondly is that of security. The United States remains the primary security guarantor in the Middle East, despite efforts to reduce its military footprint. On the other hand, China maintains a conservative approach to any security role in the region. This leads to the third pillar of foreign policy: the United States remains the closest power with most Arab countries, particularly as Iran tries to impose its expansionist policies in the region. And while China has strong Iranian ties and is pushing back against U.S. sanctions on Tehran, it assures Arab Gulf partners of its commitment to ties with them. Moreover, China’s approach of ‘non-interference’ in the internal affairs of other countries is generally liked by Arab governments. The United States has too long a history of interference. Furthermore, it is American stated policy to promote ‘democracy’ and its system of government around the world. On the other hand, the Chinese model of ‘state capitalism’ is appealing to most Arab politicians. ‘Economic liberalism’ decoupled from political liberalism is a model most governments in the region pursue, and in the past two decades, the Chinese model is lauded is a success.

This is perhaps China’s strongest ‘idea’ in appealing to governments in the Middle East. However, American soft power among general Arab publics remains firm. And this is the fourth pillar determining the future of relations, as language, popular culture, and historic familiarity continue to give the United States an advantage in people-to-people relations. However, China is exerting efforts to win over more Arabs, with a dedicated Arabic-language TV news channel, encouraging the teaching of Mandarin in a number of Arab capitals, and encouraging travel to its country. With a rising middle class in China, enjoying spending power and an interest in exploring the world, Chinese tourists are among the most sought after in the world, including the Middle East. While this is currently on hold due to COVID-19, soon visitors are likely to be admitted back in the country.

Arab countries are cognizant of Sino-American competition and understand it will continue, However, the concern is that tensions escalate. The countries of the region want to avoid becoming the stage where these tensions play out. In June 2020, UAE Minister of State for Foreign Affairs Anwar Gargash told CNBC “Every time we see confrontation between Washington and Beijing, the markets actually tremble.” He added, “And clearly I would say that competition between these two giants will continue, and to a certain extent, it will be natural. But I think we have an interest that this competition is more nuanced, and that it, at the same time, does not shake what is already a very weak international system.”

A weak international system, lacking in American leadership, is one of the concerns of the region. And these concerns have been heightened with the outbreak of COVID-19 and the American response to it. With U.S. President Donald Trump withdrawing support from the World Health Organization, blaming China for the pandemic, and largely ignoring international cooperation, the United States has abdicated its traditional role in leading efforts to meet an international crisis.

The pandemic brought to the fore key issues that have been brewing under the surface for years. Food security, economic diversification, and developing homegrown talent have all been prioritized, especially among Gulf nations. Here technological advances will be crucial and both the United States and China can offer knowledge transfer and technological solutions. However, their battle over technological domination, from AI systems to social media platforms, is being closely watched. American concerns about Chinese technology, including Huawei, are understood but not necessarily accepted in the Arab world. ‘State capitalism’ and blurred lines between the public and private sector ownership of companies is not deemed as necessarily wrong in most regional capitals. Moreover, 5G technology is seen as key to the development of tech hubs in the region – and China is a clear leaders on 5G. Huawei has signed 12 contracts for 5G in the region. The advancement of the tech sector across the world due to COVID-19 was mirrored in a number of countries in the region like the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Jordan. These countries witnessed a ‘digital transformation,’ with schools adopting e-learning, tracing apps being adopted, and new norms being set in teleworking. American technologies are not necessarily the only ones to be considered in the region.

As the countries of the region, particularly the two largest economies of Saudi Arabia and the UAE, navigate the next phase of COVID-19, they will be looking for countries with which to partner. Economic diversification, foreign direct investment, and technological advancement will be keen. While China is open to partnerships, such as the one it developed with the UAE on the delivery of clinical trials for a vaccine, the United States is visibly going its own course. That does not negate Arab interest in continuing historic partnerships with the United States, it just means other viable options exist. And not only with China. The roles of South Korea, Japan, and France, to name a few, are expanding in the region. Coming out of a pandemic and global recession, while having their own security challenges, Middle Eastern countries are looking to build their futures in a globalized system, without the hang ups of great power competition. Working on a ‘new normal’, vaccines, travel regulations and beyond, Middle Eastern countries cannot afford to continue waiting for the United States to decide on how it will engage. And so they will work to balance relations with both Washington and Beijing, across an array of sectors and strategic interests. If forced to choose between either one or the other, it is no longer the case that Washington would be the obvious choice.

Mina Al-Oraibi is an Iraqi-British journalist, currently Editor-in-Chief of The National, an English-language daily newspaper based in the UAE.