ASPI Note: South Korea Elects a Conservative Leader — Barely

March 11th, 2022 by Daniel Russel | 22/11

What Happened?

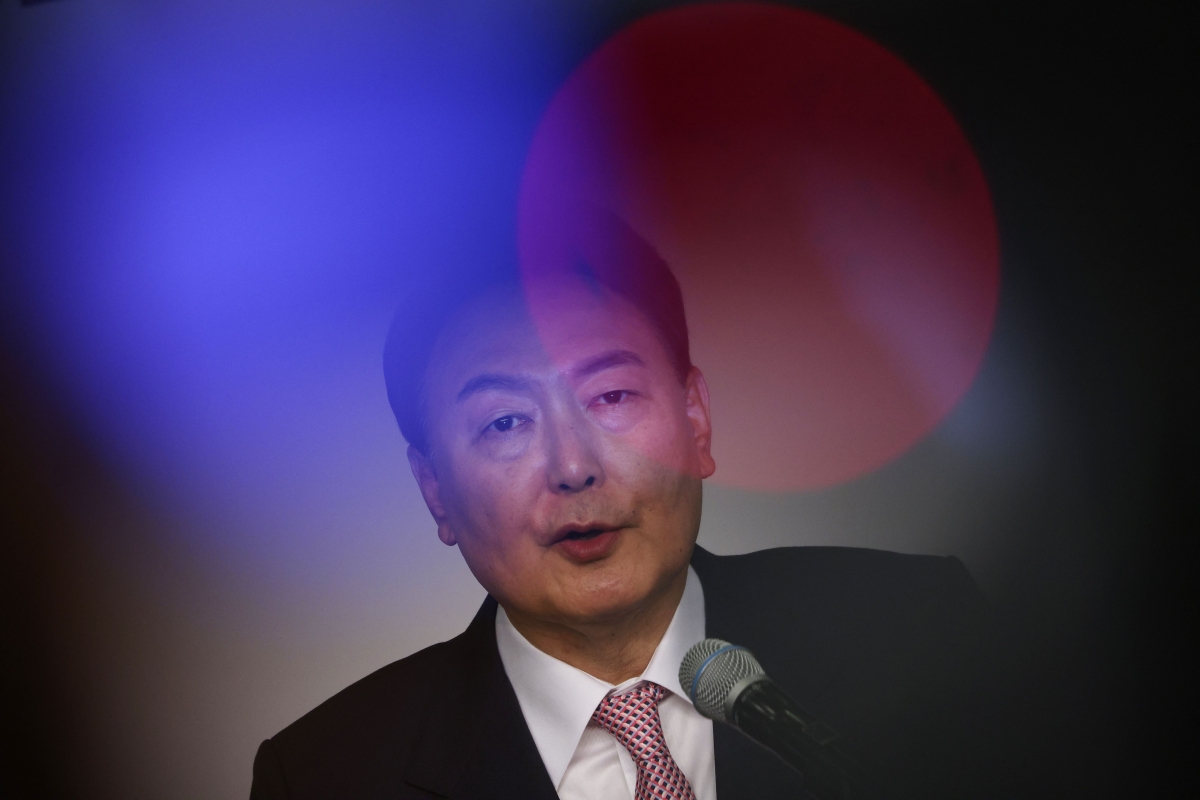

In the closest and perhaps bitterest presidential election in South Korean history, the conservative candidate Seok-youl Yoon won by only a tiny margin. The last-minute decision by a smaller party to merge with Yoon’s seems to have only narrowly taken him over the top despite discontent with Moon and his failure to deliver on economic promises, which should have led to a strong showing by the conservatives. When he is inaugurated on May 10, Yoon will be faced with a legislature controlled by the opposition, a sharply divided electorate, and myriad domestic, economic, and international challenges.

The Background:

Yoon is a former prosecutor who served in the outgoing Moon Jae-in government before the two men had a falling out. He had earned a reputation as a hardliner on anti-corruption after leading the investigation against former President Park Geun-hye. Although Yoon has a strong team of veteran economic and foreign policy advisors, he is an inexperienced, first-time politician. Korean elections are replete with scandals and mudslinging, but this election has been labeled by the press as the “Squid Games election” for the intense vitriol and dirty tricks. The election largely hinged on domestic issues. Yoon had unusually strong support from young Korean men, playing to a misogynist backlash against Moon’s push for gender equality as well as young peoples’ frustration over surging housing prices, high unemployment, and income disparity.

Yoon’s platform includes ambitious plans for economic growth emphasizing relaxing corporate regulations while supporting investment in the private sector and pursuing job creation. He has pledged a “comprehensive strategic alliance with Washington,” likely to include increased bilateral cooperation with the United States in defense, technology, and other areas. Yoon is expected to take steps to improve trilateral cooperation that includes Japan and has signaled a willingness to improve bilateral ties directly with Japan. Whereas the Moon government prioritized inter-Korean rapprochement over other foreign policy interests and fruitlessly pursued dialogue with North Korea, Yoon’s approach to Pyongyang will be weighted more heavily toward deterrence and defense in partnership with the U.S. Yoon criticized Moon for being too deferential to China, reflecting the outgoing government’s hope that China would be helpful with North Korea. Yoon’s tougher stance and stated determination to reduce economic dependence on China reflect growing anti-Chinese feeling in South Korea, where a recent poll found that 84% of Koreans now view China unfavorably.

Why it Matters:

South Korean presidents have immense executive power under the constitution with considerable leeway over national security, foreign policy, and North Korea policy in particular. Moon’s accommodationist approach to North Korea hit a dead end after the failed Trump-Kim Summit in Hanoi and caused friction between the two countries. The United States would like to see Korea more actively engaged in regional and global priorities and more supportive of its Indo-Pacific strategy. Where the Moon government held the QUAD at arm’s length in deference to Beijing, Yoon has expressed willingness to align more closely with the Biden administration’s values-based multilateral efforts, including support for the QUAD’s working groups. Yoon likely will have public backing for that approach given that a recent survey found that 75% of respondents said they would side with the United States and only 19% would side with China if forced to choose.

Digging Deeper:

Washington and Tokyo are likely breathing a sigh of relief not to face another five years of a progressive in the Blue House — both President Joe Biden and Prime Minister Fumio Kishida quickly reached out to congratulate the Korean President-elect. But Yoon comes to the job facing significant handicaps and challenges well beyond a steep learning curve. As his narrow electoral victory demonstrates, Korea is sharply divided, and he now must deal with the range of contentious social and economic issues that dominated the campaign and fueled anger towards the current government. His legislative agenda will be contested by the opposition majority in the National Assembly at least until general elections in 2024, and he will need to deal with a hostile and stubborn North Korea. If history is a guide, Yoon should expect North Korea to take provocative action early in his tenure and the North’s expanding military capabilities make that a significant risk. He can expect escalating economic and political pressure from China, high expectations from the United States, and will inherit a set of thorny and emotionally charged legacy issues with Japan. These challenges, plus the rapid surge in Omicron cases, deepening ties between Russia and China — Korea’s two largest neighbors, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and turbulence in the global economy highlight what a bumpy road lies ahead for the next Korean leader.