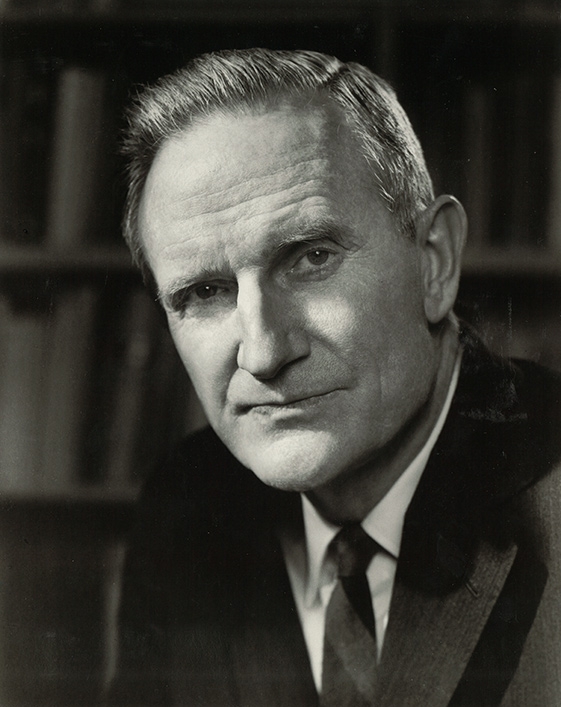

John D. Rockefeller 3rd on the Need for 'Mutual Understanding and Respect' Between East and West

Excerpts from a speech by Asia Society's founder on May 16, 1967, in New York City

Those of us who had a hand in establishing Asia Society shared a basic intent: to contribute to a broader and deeper understanding between the peoples of the United States and Asia. We felt a certain urgency to our purpose.

In 1956 the United States was already deeply engaged in Asian economic and security affairs, and many of us feared that our commitments in Asia far exceeded public understanding of why we were there, and what we hoped to accomplish.

At the same time, we founders of Asia Society were confident that Asians and Americans are capable of a richer and more meaningful mutual understanding, because of shared hopes, fears and aspirations.

Then, as now, Asians and Americans alike yearned for a world in which the human creative potential may be freed, and where each child born may have the chance to live in dignity, free from want or coercion. These were among America’s goals in our own Revolutionary War, and similar goals have more recently inspired Asian independence leaders and nation builders.

One of the most important challenges to Asian leadership — and to Americans and other Westerners working with them — is to learn how to modernize Asia without westernizing it; to learn what tools and techniques to borrow and adapt from the West, in order to manage material progress, without sacrificing the values that have made the East culturally rich.

Asians, like Americans, are impatient for results, but not at the cost of abandoning their own traditions, dismantling thousands of years of social customs, and becoming pale copies of the efficient American stereotype.

This situation calls for the American aid administrator, teacher, community developer, and in an important sense, the American businessman in Asia, not only to be an expert in his own field of specialization, but also to become an expert in the dynamics of the Asian culture in which he is working, and which he hopes to help modernize.

In a sense, the American working in Asia needs to understand the difference between the good salesman who delivers to his customer a new and fully equipped car, and the master mechanic who takes on the far more difficult job of helping the customer modernize his existing vehicle one part at a time, while the two of them keep the engine tuned up and running, throughout the rebuilding process.

This is asking an extraordinary amount of mutual understanding at the personal, interacting level. I realize that, but I am confident it is possible. It is an ideal that has animated the Peace Corps and many successful teaching projects, and I am convinced that the rewards will flow both ways from this kind of East-West partnership. Westerners can learn much from helping Easterners solve their own problems. Equally important, it is only on these terms that Asians are likely to achieve self-respecting independence.

America can encourage and learn to live with an independent-minded Asia because we do share common aspirations — aspirations that stem from our historic beliefs in the dignity of the individual.

This identity of basic goals is the real foundation for Asian-American understanding, and the real justification for the work of organizations such as Asia Society. It is a bond that should lead us to a mutual understanding and respect based, not on mere tolerance of our differences, but on our awareness that the world is richer for those differences, and we as individuals are thereby richer in our humanity.

Go back to the 60th Anniversary main page.