Vietnam

A Historical Introduction

Although the history of any region is the product of a complex mix of culture and circumstance, in many ways, for Vietnam, geography is destiny. To understand Vietnam's history it is imperative to have aclear picture of the land and the region.

Vietnam's geographical position relative to China has been paramount in shaping its political and cultural history. On the map, Vietnam is directly below China—an elongated, 1,000-mile-long "S," containing in its northern loop the great population center of the Red River delta and in its southern loop that of the Mekong River delta. Vietnam attained this shape through slow, painful expansion from its northern delta (settled before the Christian era) to the Mekong region. This expansion took place mainly between the 10th and the 18th centuries A.D.

The Vietnamese nation arose from the many clans and communities of the Viet peoples, stretching from the area of present-day Shanghai down to the Red River delta, where Hanoi is now located. The climate of this region is ruled by the monsoon rains that fall between May and October. The principal crop is rice, requiring systematic management of the water supply for its cultivation. In the Red River delta, controlling the river is the key to production and survival. The coastal economies of the Viet region usually included fishing and local shipping.

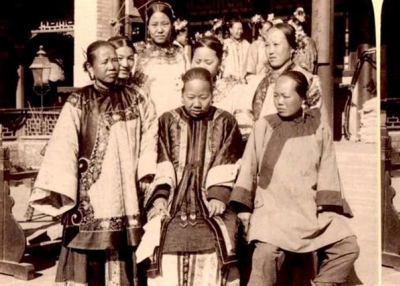

About 100 B.C.E. the Han, China's most powerful dynasty, conquered the Viet regions and incorporated their territory into the Chinese empire as provinces. Over the next 1,000 years most of the Vietnamese were absorbed into Chinese society, becoming part of the present-day provinces of Yunnan, Fujian (Fukien), Guangdong (Kwangtung), and Guangxi (Kwangsi). Only the southernmost group, the Vietnamese of the Red River delta, managed to preserve their own language and other elements of independence—among them, the stronger economic and social position of women. In the main, the Vietnamese of the Red River delta accepted their homeland's status as a part of the Chinese empire, cooperating with Chinese administrations. Although there were occasional rebellions and declarations of independent Vietnamese governments, they were no match for the stronger Chinese dynasties that dominated them.

Under this millennium of Chinese rule, from about 100 B.C.E. to 1,000 C.E., the Vietnamese made certain gains. They learned how to improve their agriculture and water control. The Mon-Khmer speaking elite adapted the Chinese systems of education and bureaucracy to suit their needs; and, while retaining their native spoken language, mastered the Chinese written language.

Early in the 10th century, at a time of dynastic change and military weakness in China, the Vietnamese of the Red River delta succeeded in establishing an independent Vietnam. Chinese provincial names were discarded, and Chinese authority came to an end. And yet, the Vietnamese preserved many Chinese forms of social organization. They set up a native dynasty, with an emperor who directed the bureaucracy. In this way they governed the land and defended against Chinese attempts to reconquer their lost territory. Vietnam was on the way to becoming a China in miniature; but relations with China—now fraternal, now fratricidal—were a continuing problem.

The China question apart, Vietnam began a new phase of its history in the 10th century. With independence, it grew to geographic maturity, enlarged its role in southeast Asia, and came into conflict with a series of European military and cultural invaders.

Even before the 10th century, the Vietnamese had been pushing south from the Red River delta. From the 10th to the 18th centuries, the progressive extension of farmer-soldier settlements became the dominant motif of Vietnamese history. This advance displaced many peoples—notably the Cham, who had been more influenced by Indian than Chinese culture. The victims of Vietnam's expansion were either absorbed by the conquerors or driven west into the areas now known as Laos and Cambodia, where Indian cultural influences are still strong.

The Vietnamese name for this advance, Nam Tien, or "March to the South," suggests its military character. One of the principal motivations for the "March" was the sudden, uncontrollable flooding of the Red River, which drove peasants south in search of farmland. Another factor was historical rather than natural. In each of the last four Chinese dynasties—the Song (Sung), the Mongol-ruled Yuan (Yüan), the Ming, and the Manchu-ruled Qing (Ch'ing)—Vietnam suffered and overcame Chinese invasion. The Vietnamese government rewarded its fighting men with farmland to the south. Behind these aggressive pioneers came other settlers. The Vietnamese often met resistance from the Cham and had to yield ground, but in the long run their "March to the South" could not be stopped.

The formative process of Vietnam's history culminated in the settlement of the Mekong River delta. In the course of the 19th and 20th centuries, this area, dominated by the major city of Saigon, rapidly became the rice bowl for all Vietnam. The delta became the second great population center, and Vietnam took the shape it has today.

The two loops of the "S" are connected by a cultivable strip of coastal land. This coastline has played a key role in Vietnam's history, reinforcing the often fragile unity between north and south. The coast, moreover, has given Vietnam international importance because it commands the South China Sea and occupies a central strategic position with respect to present-day India, Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, and southern China. To the Japanese and Europeans who were invading southeast Asian waters in the 16th century, Vietnam had even more geographic than commercial appeal.

Since then, Vietnam has endured foreign intrusions by various countries—Portugal, the Netherlands, France, China, Japan, and the United States. For some three-quarters of a century, until after World War II, Vietnam was a French colony. But eventually every invader was driven off. Many Vietnamese place this "modern" experience in the longer perspective of their defeat of earlier invasions by Chinese and Mongols. These complex and bitter experiences have created in the Vietnamese an intense national consciousness of their history that has helped them defend their independence against many powerful enemies.