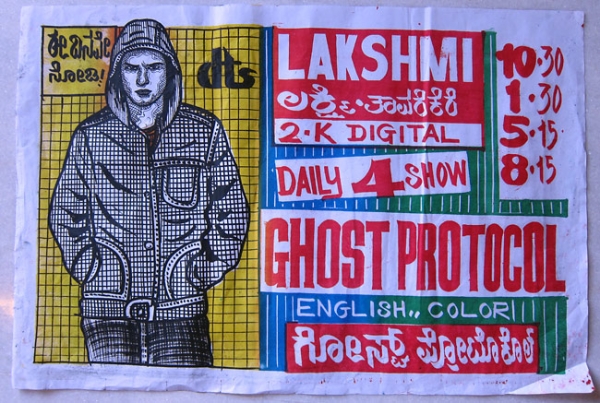

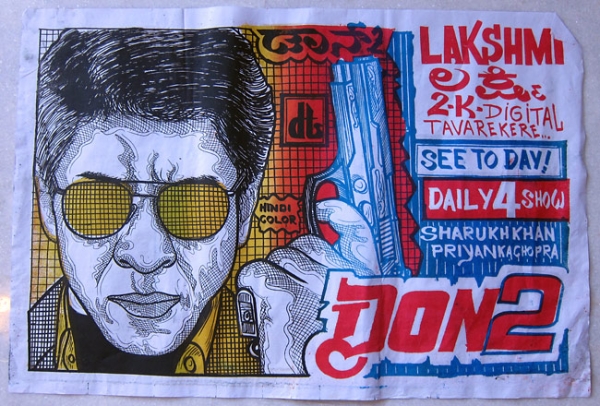

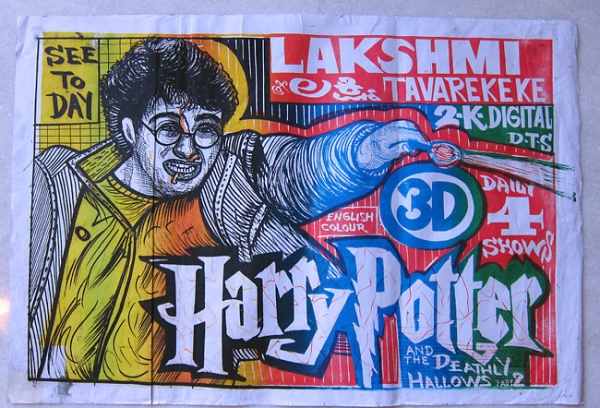

Gallery: Hand-Drawn Indian Movie Posters Convey 'Passion, Power and Immediacy'

Movie posters, kitschy or not, are art. Iconic images from cinema have become an integral part of our pop culture landscape. It's hard to imagine our 20th-century consciousness without images created by poster artists like Howard Terpning (The Sound of Music, Doctor Zhivago), Reynold Brown (Attack of the 50-Foot Woman), and Saul Bass (Vertigo, The Shining).

India's rich cinema culture boasts its own share of memorable poster images from artists like D.R. Bhosale (Guide, 1965), C. Mohan (Sholay, 1975) and Diwakar Karkare (Silsila, 1981). Then there are the countless artists whose posters are emblazoned along roadside stands and stalls whose names are largely unrecognized.

Andy Deemer, a filmmaker and the entrepreneur/curator behind the blog Asia Obscura, was hypnotized by the colorful posters he saw along the streets in India. He went in search of artists behind these images, and his journey eventually took him to a small, mom-and-pop poster shop in Bangalore called Ramachandraiah's. When Andy realized that the owners did custom orders, the movie geek in him had a field day. Requests were made not only for Bollywood films but also for some of Andy's own favorites, like Sixteen Candles, as well as ones from his own stint as the auteur responsible for exploitation horror flicks like Poultrygeist.

Reached via email, Andy told Asia Blog about how he discovered Ramachandraiah's rare and extraordinary work and what this art means to him.

You mention that it took you a month to locate Ramachandraiah's poster shop. How did you first become aware of his and his illustrator Raju's posters? Do you know if they have any kind of fan following besides you — whether in the greater Bangalore area, or online?

Arriving in Bangalore was sensory overload. Jet lag, traffic, noise, plus the painted cows, wandering goats, piles of trash... I couldn't focus on anything. But then, crossing a street, I saw something so dramatic that I was almost hit by a rickshaw. It was slapped up against a brick wall, and it was beautiful. A poster for a movie, although I didn't know it was a movie. Unevenly hand-drawn, printed in garish colors, it showed a man with a terrific mustache and criss-crossed sunglasses, raising a fist in anger. A drop of blood was splashed across his cheek. There were snippets of bold Kannada script, proclaiming something important. I had to find out what this was, where I could get a copy. And while I was gazing at it, a stranger stopped on the sidewalk, unzipped his fly, and started urinating against it.

The posters are illegal, slapped up in the middle of the night by guerrilla promoters, and aren't locally considered art — they're usually called an urban blight. There's a small fan base, mostly overseas, but it's growing. The Weinstein Company recently contacted me for a handful of them, which now hang in their offices above posters for The Artist. The writer of the Bollywood hit Delhi Belly apparently gushed, jealously, when he saw his film's poster in a friend's apartment. And every now and then a filmmaker contacts me, eager for the poster for their film. I try to help out when I can...

Can you summarize what it is about these posters that you respond to? Do you think your own background as a filmmaker informs your reaction to them?

They're not marketing campaigns created in a boardroom by a team of executives and designers, they're outsider art created by a theater owner and a man sitting on a small wooden stool on the sidewalk. They're gratuitous, exploitative, so immediately and overwhelmingly passionate. They dare you to look away. In that way, they're a lot like popular Indian cinema: passion, power, immediacy. They use the bold strokes of German expressionism, with the strength of communist propaganda. And, of course, that outsider touch. (These were the greatest things I'd seen since the hand-painted African movie posters.)

Most of the films I've worked on have been pure exploitation — cheap, trashy, and wonderful horror films like Monsturd and Poultrygeist: Night of the Chicken Dead. These movies embrace the same aesthetic: passion, power and immediacy. From the titles, you know what you're getting. From Ramachandraiah's posters, you know what you're getting.

It's interesting that in the depiction of the stars in these posters, the likeness is close, but a little off in some respects. Tom Cruise doesn't exactly look like Tom Cruise, Shahrukh Khan doesn't exactly look like himself, etc. Which adds to the charm and idiosyncrasy of this art form. The draughtsman takes his own approach and kind of makes the poster his own. What's your take on this?

Yes! The process is telling... Raju sits at a drafting table on the sidewalk. His canvas is a thin piece of paper, 30x20, held down with rocks to keep it from blowing away. He has a scrap of paper with the movie's title, in Kannada or Hindi or Tamil or English, and the theater name and specs — if it's showing three or five times a day, if it's an air-conditioned theater, if the sound is DTS. Sometimes he traces a blown-up xerox of a movie still, but often he just eyeballs it, adding his own flourishes and style. He'll spend just a few hours drawing each movie poster, and then passes it down the production line, eventually to the 1901 lithograph it's printed on. He churns out posters for dozens of movies a week, every week.

Recently, I've been working with an amazing artist named Mr. Chinappa. He's in his 80s, but works around the clock painting 40-foot-tall, or taller, cutouts. (I'm not sure if you're familiar with these, but they're exactly what they sound like: a gargantuan cutout of the movie's star, to be posed outside the theater for the opening week. Usually garlands are hung around the neck, incense is burned, milk is poured over them — it's a very holy experience.) Mr. Chinappa's been doing these his entire life. At this point, he can just stand before an 8-foot-tall section of plywood, representing the legs perhaps, and — holding an A4-sized color printout as a guide — eyeball the painting. He takes just a few days for each of these.

More and more, though, these posters and cutouts are being produced digitally. Instead of the old artisans, they're churned out in minutes using flex print technology, which looks horrible buts costs just a fraction.

Mr. Chinappa says he'll retire later this month. Another sign-painter I work with hass been reduced to selling license plate decals out of a cabinet squeezed under a staircase. It's sad that the hand-produced commercial art trade is dying so quickly, but I guess it is everywhere.

These artists are invariably confused by my orders: a hand-painted billboard for a 1971 Kannada movie, litho posters for old Italian horror films and Japanese cartoons, a metal sign advertising a non-existent ice cream shop. But they also appreciate the work.

You can find a more extensive array of Ramachandraiah and Raju's creations on Andy Deemer's blog, Asia Obscura.