Tsai Ming-Liang: 'Cinema Has Its Own Realism'

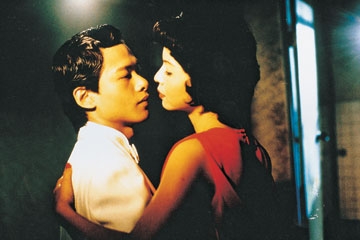

NEW YORK, November 17, 2009 — Malaysian-born, Taiwan-based filmmaker Tsai Ming-Liang and his long-term collaborator, actor Lee Kang-Sheng, met with the audience at the Asia Society New York Center for the Faces of Tsai Ming-Liang film series (November 13-21, 2009).

In a discussion conducted by series curator La Frances Hui, Senior Program Officer of Cultural Programs, Asia Society, the director, who often employs long, static takes to depict the most mundane daily activities, distinguished between realism in real life and realism on film, explaining that in treating real life as dreams, he strives for an "internal" realism. He also discussed the use of music as a counterpoint to contemporary life and the human condition portrayed in his films, and how important it is for his viewers to maintain a certain distance when watching his films.

Watch the video above for Tsai Ming-Liang's remarks, or read the transcript below.

T: Tsai Ming-Liang (film director)

La Frances Hui (interviewer)

T: ... For example, in Taiwan and India, filmmaking is like dreammaking. The dreams are escapist. I also enjoy watching those films. But when I make my films, I like to be closer to reality. Slowly, I realized how hard it is to capture reality. What is real? What is a realistic performance by an actor? When I film actors, I usually give them instructions, but then I regret doing so. So I wait till they have finished all my instructions, and then keep the camera rolling. I wait to see what else they'll do, until a point of ambiguity. At that point, things become real.

Slowly, I realized realism in cinema is not the same as realism in life. Cinema has its own realism. The world in cinema is not the real world. It has been crafted. That makes cinema interesting. It's not real. It's closer to dreams. If you treat life as a dream, you can understand this. My later films became freer because my realism doesn't have to be like real life. My realism can be treated as dreams. But they are still realistic with a lot of absurdities. So my later films are more internal. I don't care so much about external reality. That's why you don't see computers in my films because they are not realistic. (chuckles)

My musical sequences take place on the existing sets. I don't build separate sets for the musical numbers. I am most interested in the songs—their lyrics, genres, and moods. Songs have their age. They are from different eras. They are embedded in my memories. Those songs are from my childhood and adolescence. They are deeply embedded in my mind. They become part of my life. When I use them, I treat them as an element. They act as a counterpoint. For example, the songs' passion, innocence, lyrics, genres, and how they are interpreted are in conflict with my treatment of contemporary life and the human condition. They act as a counterpoint.

I am interested in mentioning the last musical sequence in Face (2009). There's actually no music. There's only dance. It's kind of a musical without music. I used sound elements on the set to create rhythm and expression. It's kind of a dissection on the possibility of film. I like to deconstruct, including to deconstruct the concept of celluloid. For example, I would make the entire film silent, with only some simple sounds left. Omitted is the music we are used to.

I want the audience to be constantly reminded that they are watching a film. They are watching a film in the theater. There's a distance. They should have a viewing attitude. There's no need to be absorbed in the viewing. They can choose to be absorbed and also to pull back. For example, with Yang Kuei-Mel's cry [in the last scene of Vive L'Amour (1994)], there should be a distance in the viewing. The viewers should not cry along with Yang Kuei-Mei. It's like the writer I like very much, Brecht. When you are sitting in the theater, you should be aware of that. You should be aware of the fact that you are watching a work of art. So you wouldn't be completely absorbed. That's my ideal.

Video and text report produced by La Frances Hui.

Live on-stage conversations translated by Vincent Cheng.

Transcript and video subtitles translated by La Frances Hui.

Asia Society's Faces of Tsai Ming-Liang film series (November 13-21, 2009) was co-presented with Taipei Economic and Cultural Office in New York. The series was part of Citi Series on Asian Arts and Culture, sponsored by the Citi Foundation. Additional support was provided by the New York State Council on the Arts.