A World-Class Fix for Schools

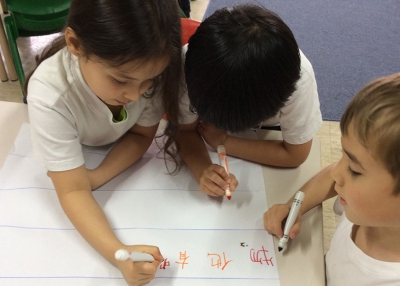

In his quest to improve America’s schools, President Obama has called for innovation and globalization. Successful models for that innovation can be found right in the former backyard of both Obama and new Secretary of Education Arne Duncan. On a typical morning at Walter Payton College Prep High School in Chicago, students are greeted warmly by a guest instructor for the day. One day the guest may be from nearly 5,000 miles away in Switzerland, connected through the school’s state-of-the-art videoconference system. Another day there may be a teacher connected to the school from China. In math classes, students work on problems that come from peers as far away as France, India and Japan.

At Walter Payton College Prep, a citywide magnet school, black students make up roughly 25 percent of the student body and Hispanics constitute roughly 21 percent. The school's curriculum and philosophy take dead aim on two entwined imperatives facing American education: the persistent problem of underachievement and high dropout rates, particularly among non-white and low-income students, and the equally urgent need to prepare all students for work and civic roles in a globalized environment, where success increasingly requires the ability to compete, connect and cooperate on an international scale.

Duncan’s record in Chicago suggests he is up to the challenge of fostering the growth of more schools like Payton. He pushed for consistency and rigor in the K-12 curriculum and, amid other reforms, championed the creation of small, more engaging schools across the city. At the same time, he created the largest Chinese language program in the United States and, in Walter Payton College Prep, established one of the country’s best public schools focusing on international education.

Building on new funding contained in the emergency economic stimulus package, Duncan’s next big challenge will be “fixing” No Child Left Behind, the current title of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, which has, in various iterations since the mid-1960s, been one of the primary means by which the federal government influences education for economically disadvantaged students. The central goal of the law, like most other federal education programs, has been to create equal educational opportunity. Under No Child Left Behind, however, the primary focus has been closing the achievement gap between racial and socioeconomic groups on standardized tests rather than the more robust earlier goal of eliminating differences in the quality of public education provided to rich and poor students. Of course it is important to close the achievement gap on basic skills and to create appropriate models for holding students, teachers and schools accountable for academic progress. But to stop there would be to, again, leave the glass half empty for those who have already been shortchanged.

Three years ago, at the groundbreaking for the Vaughn International Studies Academy in the gritty, primarily low-income community of Pacoima, near Los Angeles, a reporter asked, “But why do those kids need to know about the world?” The assumption behind the question was clear. It’s hard enough to simply graduate low-income minority students from high school and get them into college. Why bother to teach them about the world beyond U.S. borders?

The full measure of what disadvantaged students need in a global age is what all students need: deep knowledge about other cultures; sophisticated communication skills, including the ability to speak at least one language in addition to English; expert thinking skills required in a knowledge-driven global economy; and the disposition to positively interact with individuals from varied backgrounds. These are the foundations of work and citizenship in the 21st century. And they are the foundations of meaningful education reform.

There is ample evidence that a comprehensive approach to global education works. Just ask the parents of students at John Stanford International School, a high-achieving public elementary bilingual immersion school in Seattle where a broadly diverse student population spends half the day studying math, science, culture and literacy in either Japanese or Spanish and the other half learning reading, writing and social studies in English. The Denver Center for International Studies in just three years has become one of the most sought-after magnet schools in the city. Students there in grades 6 through 12 study one of five world languages offered for seven years; experience international travel and exchanges with schools in Asia, Europe and Latin America; and learn through partnerships with a wide array of internationally focused organizations.

The key to the success of these schools is that they do not merely layer on an international perspective once the basics are covered or reserve international content for a select few; rather, they use a global focus to deeply engage all students in learning.

Duncan’s simultaneous attack in Chicago on the age-old problem of poor academic achievement and the new demands of globalization is precisely what is needed on a national scale. The right to an excellent education is the civil rights issue of the 21st century, and building global competence among all American students is, indeed, the new definition of equal educational opportunity.

Author: Anthony Jackson