How the Asian Financial Crisis Led to China’s Massive Graduate Unemployment

Students pack into a Chengdu, China job fair in 2005. Some 40,000 students competed for 10,000 jobs at the fair. (China Photos/Getty Images)

For years, nearly the same story has been reported every summer in China: record numbers of new college graduates are grappling with record job shortages.

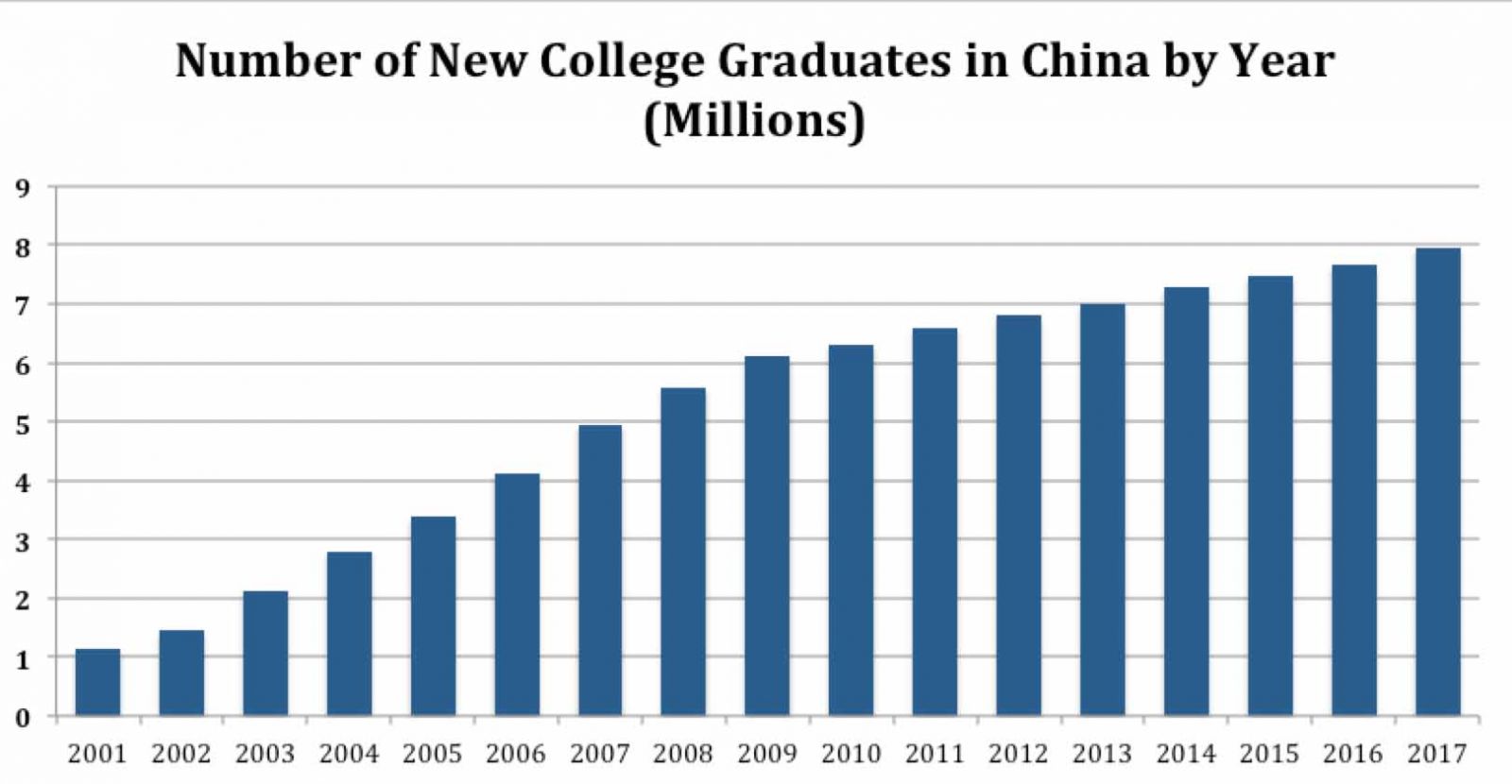

2013 was dubbed the "hardest job-hunting season in history," when 7 million new graduates packed shoulder-to-shoulder into job fairs with few opportunities available. But in hindsight, that “tough” season was relatively mild: This year, there are nearly 8 million new graduates expected. And as of June 1, only about 27 percent had signed employment contracts — down from 35 percent at the same time last year — and average graduate wages have declined 16 percent over the same period.

The problem has been widely reported, but its origins haven’t. In a 2014 paper based on newly available documents and memoirs, Shanghai University Political Scientist Qinghua Wang argued that it has roots in the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis when China’s top leaders calculated that a dramatic rise in higher education enrollment would help preserve social stability and their own power.

“[It] was antithetical to regularized educational policy-making in post-Mao China,” Wang wrote. “The side-effects on higher education were of secondary importance when the [Communist] Party considered that its rule was threatened.”

Source: China's Ministry of Education

Throughout the 1990s, China underwent massive privatization of state-owned enterprises (SOEs), which resulted in millions of layoffs. The country needed to maintain high growth rates to absorb the shock, but the arrival of the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997 posed a threat to that model. Shrinking markets, currency devaluations, and dwindling foreign direct investment from Asian neighbors undercut China’s export-led growth model, slashing export growth from 17.3 percent in 1996 to 0.5 percent in 1998. Similar pressures fueled student protests in 1998 that ended the three-decade reign of Indonesian President Suharto, which prompted some analysts to wonder whether China might become “another Indonesia.”

In late 1998, then-Chinese President Jiang Zemin said that domestic consumption would need to rise to make up for lagging exports. Economists identified one area where there existed huge demand from the public, but little supply: higher education. The thinking went that significantly increasing college enrollment would boost spending associated with education, create jobs, and free up employment opportunities for laid-off SOE workers by keeping more young people out of the job market for a few years.

However, the proposal was strongly opposed by many education officials — particularly Chief of the Ministry of Education Department of Development and Planning Ji Baocheng. For years, he had been advocating “steady development” of Chinese higher education, saying that if enrollment increased too quickly, students would expect to gain elite jobs that the economy would be unable to provide. “The Ministry of Education should not expand recruitment further for the purpose of boosting domestic demand,” Ji reportedly said after the enrollment increase was proposed in 1999. “Otherwise, it will be very difficult to manage the entire education situation in the future.”

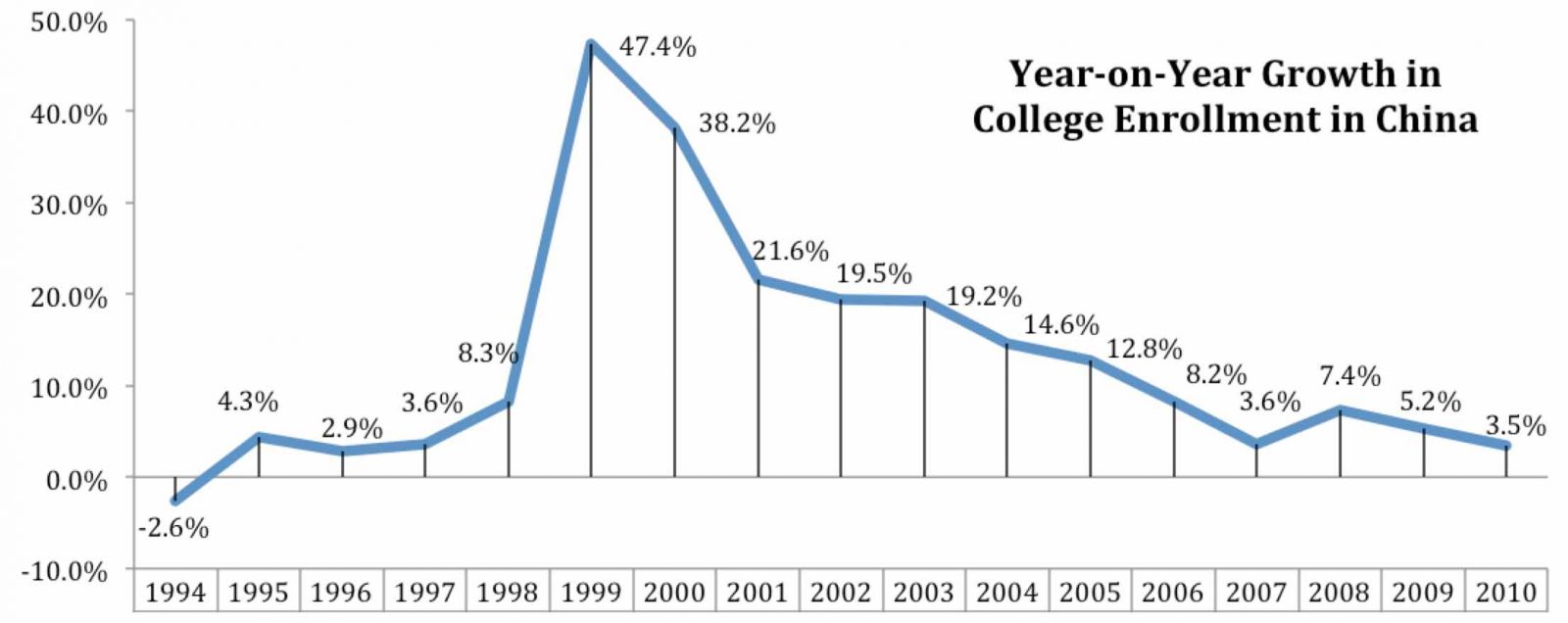

Nevertheless, China’s State Council issued an order in April of 1999 to revise recruitment plans for the coming autumn. Because plans would have to be finalized by the college entrance exam in June, there was no time for substantive feasibility studies. On June 24 — under the authorization of China’s all-powerful Politburo Standing Committee — it was announced that an additional 500,000 students would be enrolled in higher education institutions in the coming school year. This represented a 47 percent increase over the previous year, compared to an average of just over 3 percent annual growth over the preceding five years.

In his paper, Wang said that this decision was “strikingly irregular,” as the Politburo Standing Committee’s overriding of the Education Ministry circumvented standard education policy-making procedure. “The top leadership’s interference was forceful, disruptive, and non-professional,” Wang wrote. “The rationale for Party interference was political.”

Between 1998 and 2000, the number of college freshmen roughly doubled. To accommodate this increase, universities rapidly expanded their facilities and faculty, for which they were encouraged to borrow from state-owned banks (a practice that led to widespread debt problems years later). It didn’t take long for quality problems stemming from a lack of adequate funding and qualified teachers to emerge. In 2001, the Ministry of Education decided enrollment growth should be capped at around 5 percent per year.

However, universities had several incentives to continue expanding at higher rates than the Education Ministry targets. In a separate 2016 paper, Qinghua Wang notes that by becoming “bigger and more comprehensive,” schools could gain a higher ranking and official status — something that also entitled school officials to higher bureaucratic rankings and greater perks. And since government funding was allocated on a per-student basis, increasing enrollment also meant more money. So for several years, schools continued to expand, vocational colleges became full universities, and some institutions added dozens of majors — many of which were considered “hot” fields that could earn schools substantial revenue. This, in turn, created competition among universities. “The underlying mentality can be summarized as ‘Whatever new majors you have, I will have them too,’” Wang wrote. “‘In this way, I will not be in a disadvantageous position.’”

Source: Qinghua Wang. "The ‘Great Leap Forward’ in Chinese Higher Education, 1999–2005: An Analysis of the Contributing Factors."

By 2006, the Ministry of Education began to regain control over the situation. After seven straight years of double-digit year-on-year growth in higher education enrollment, annual recruitment slowed back to single-digit growth. But the damage had already been done. Huge discrepancies between the supply of college graduates and demand in the workforce were emerging.

In 2009, Lian Si, a professor at Beijing’s University of International Business and Economics, published the groundbreaking book Ant Tribe, which documented some of the estimated one million college graduates living on the outskirts of major cities in cheap, often squalid, conditions. Because of the rapid devaluation of college degrees, they were unable to find good white-collar work — yet their degrees had instilled a conviction that they would eventually achieve the high-status careers they craved. “They share every similarity with ants,” Lian wrote in his book. “They live in colonies in cramped areas. They are intelligent and hardworking, yet anonymous and underpaid.”

The politically motivated decision back in 1999 to dramatically expand enrollment in order to maintain social stability could ultimately have the opposite effect. Qinghua Wang said that major issues with Chinese higher education quality and debt are legacies of the massive enrollment expansion of 1999 to 2006. “The gravest concern for the government, however, has been graduate unemployment,” Wang wrote. “Because it relates directly to social and political stability.”