For Heritage Month, Remembering 'One of a Kind' Painter Yasuo Kuniyoshi

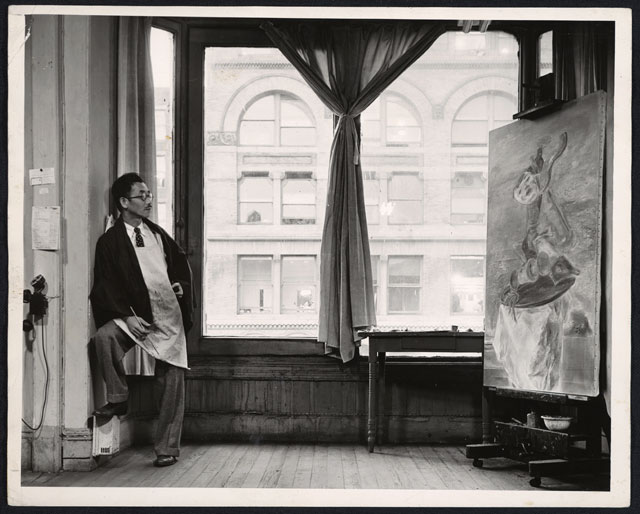

Yasuo Kuniyoshi in his studio at 20 East 14th Street in New York City on October 31, 1940. (Max Yavno/W.P.A./Archives of American Art)

Readers of Asia Blog are most likely already aware that May marks Asian Pacific American Heritage Month. This gives us an opportunity to reflect on the contributions that so many Asian Americans have made in our lives, some famous, others relatively unsung.

As a former graduate student of art history and American art, I couldn't help but think of the artist Yasuo Kuniyoshi. A contemporary of artists like Reginald Marsh and Mark Rothko, Kuniyoshi is considered by scholars and critics to be the best-known Japanese American painter of the interwar years.

Born in Okayama, Japan in 1893, Kuniyoshi moved to the United States as a teenager and settled first on the West Coast. He discovered his calling as an artist and enrolled as a student at the California School of Art and Design in Los Angeles. He eventually moved to New York City and studied at the Art Students League, the school with which he would be associated for the rest of his career.

Kuniyoshi's most distinctive work of the early 1920s blends elements of American folk tradition, Japanese prints, and the lines and angles of European modernism (specifically, Cubism). A part-time resident of Maine, he was drawn to the countryside of his adopted homeland. Earth tones, warm colors, cows, lighthouses, bathers on the beach, are all aspects of his work during this time.

Tatsiana Zhurauliova, a PhD candidate in art history at Yale University who is writing her dissertation on Kuniyoshi, spoke with Asia Blog about the key elements of his style:

Throughout his prolific career, Kuniyoshi worked in a variety of different media, such as painting, photography, and printmaking, incessantly enriching his artistic vocabulary and constantly reinventing himself in his art. His painterly works from the 1920s are characterized by an expressive distortion of form and perspective, which was in part inspired by the artist's early interest in American folk art, Japanese traditional painting, and European Modernism.

In contrast, Kuniyoshi's compositions from the late 1930s and early 1940s adhere to a more realistic tradition in their use of linear perspective, which suggests depth and spatial continuity. For instance, his wartime landscapes depict a variety of Western ghost towns and show empty streets that are overgrown with grass and unkempt buildings, which gradually dissolve into the surrounding scenery. The artist's use of quick, feathery brushstrokes highlights the wretched quality of these remnants of human civilization, visualizing the process of its erasure by natural forces. Deeply concerned with World War II and its effects both overseas and on the home front, these works reflect the complex personal, national, and global ramifications of changing geopolitical and geocultural paradigms brought by war.

Being Japanese in America in the years leading up to the war brought its own share of difficulties. When Kuniyoshi married his fellow Art Student League class member Katherine Schmidt in 1919, she lost her citizenship for marrying an alien ineligible for citizenship himself. During World War II, the government classified Kuniyoshi as an enemy alien. He was placed under surveillance and his bank account was impounded. Only by helping the Office of War Information with propaganda art and broadcasting pro-democracy messages through the radio could Kuniyoshi avoid the internment camps.

In 1948, the Whitney Museum of American Art held a retrospective of Kuniyoshi's work — the Whitney's first solo show for a living American artist at that time and the first for an Asian American. After 1949, there was a shift in Kuniyoshi's style toward brighter, more vivid primary colors and images of clowns, reminiscent of the themes seen in some of the works of Picasso and Aleksander Rodchenko.

ShiPu Wang, a professor of art history at the University of California, Merced, is the author of a recent book on the artist, Becoming American? The Art and Identity Crisis of Yasuo Kuniyoshi (University of Hawaii Press, 2011). Via email, Dr. Wang explained the remarkable nature of Kuniyoshi's contributions to American art:

Yasuo Kuniyoshi was an outlier of an artist. He was arguably the only emigrant artist of Japanese descent to achieve sustained prominence for over two decades in the exclusive, largely Caucasian New York art scene. He was also the most renowned "enemy alien" artist to volunteer to contribute to the U.S. "anti-Japan" propaganda programs during World War II. In 1948, the Whitney Museum of American Art honored him with the institution's first-ever retrospective of a living artist, and he represented American art at the 1952 Venice Biennale while he was still legally a "foreigner." An influential teacher, an active member and leader of important artists' groups, and an artist who won virtually all major awards in American art, Kuniyoshi was one of a kind.

When Kuniyoshi passed away in 1953, he had established himself as an artist who defied broad categories and easy generalizations during one of the most tumultuous periods in modern American history.

Video: Watch a slideshow of Yasuo Kuniyoshi's paintings (3 min., 23 sec.)