'Descent Into Darkness': Looking Back at the My Lai Massacre

A display at the My Lai Memorial Site in My Lai village, Vietnam. (Adam Jones/Flickr)

On March 16, 1968, a U.S. Army platoon was sent on a search and destroy mission to a South Vietnamese village thought to be sheltering Viet Cong guerrillas. What happened next became one of the most infamous episodes in American military history.

Over the course of four hours, U.S. soldiers raped, murdered, and mutilated unarmed civilians, including the elderly, pregnant women, children, and infants. This continued until a three-man American helicopter crew flying overhead witnessed the carnage and intervened by landing between a group of fleeing villagers and U.S. soldiers pursuing them, telling the latter to stand down or be shot. The incident became known as the My Lai Massacre, named after the village in which it occurred. As many as 504 civilians were estimated to have been killed that day — none confirmed to be Viet Cong.

A cover-up orchestrated by the Army ensured that the event remained unknown to the public for more than a year until witnesses spoke up and the story was uncovered by the media. Ultimately, 14 men were charged with crimes relating to My Lai. Only one — platoon leader Lt. William Calley — was prosecuted. After being convicted of murdering 22 unarmed civilians and sentenced to life in prison, President Richard Nixon controversially ordered him transferred to house arrest to await appeal. He was paroled after three and a half years.

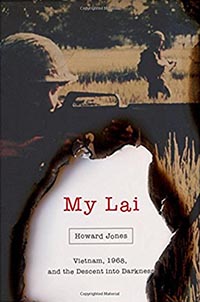

In the new book My Lai: Vietnam, 1968, and the Descent into Darkness, University of Alabama History Professor Emeritus Howard Jones looks back at the events and their aftermath in a chronological 475-page narrative based on original archival research and eyewitness interviews. In an interview with Asia Blog, Jones discusses the massacre and its legacy.

The main question that’s always surrounded My Lai is “Why did it happen?” What are your thoughts about this question?

I tried to deal with this key question throughout my work and could never really find a definitive answer. But there were contributing factors.

At his trial, William Calley admitted that he fired into a ditch with 50 to 100 dead or dying civilians and made the comment to a superior that it was no big deal, they were the enemy. But why children? He said that “they grow up to be Viet Cong.”

This was a very different kind of war in that all Viet Cong were Vietnamese but not all Vietnamese were Viet Cong. So how do you distinguish one from the other in combat? One soldier simply said, “Kill them all and let God sort them out.” This was again why I was so drawn to this topic — because it sheds light on the whole war in Vietnam. This wasn’t a war against civilians, but they were the ones who paid the biggest price. The strategy to win was body counts. It was search and destroy, and you had free fire zones [areas where all unidentified persons were considered enemies and soldiers were to fire on them].

Then there was the lack of leadership — a lack of officers who had courage and ethics. Soldiers, including officers, lined up to gang rape women and girls. And there were soldiers who bragged about it. You were considered a "double veteran" if you raped a girl and killed her. There were around 19 who were actually accused of this crime at My Lai and there were certainly more [who weren't]. One soldier named Dennis Bunning tried to put a stop to it, only to encounter five or six others who hauled him off to the side, put a gun to his head, and warned, "One more word and we're leaving you in the bush." No one would ever know what happened to him. They weren't in a place where there was law and order or rules. So he shut up and there was nothing more he could do.

Major William Eckhardt [the chief Army prosecutor of the My Lai cases] told me that one of the biggest things that had to be done when it was all over was to put this directive in writing for the Army: "You don't kill civilians — unarmed, defenseless civilians.” As blatantly clear as that order should have been, it had to be in writing.

This event also showed that the Army must do everything it can to recruit soldiers who have character, who have some kind of inner core belief of what is right and wrong. That was a real problem because bringing people into the American forces became a major issue in Vietnam as the war went on. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara started a program to accept 100,000 recruits that had been previously rejected for military service, so that was another big problem.

How exceptional was My Lai?

The Army itself had a special private group investigating alleged massacres during the course of the Vietnam War and the materials it gathered only recently became available at the National Archives. They show well over 300 cases of civilian massacres. But I think General William Westmoreland [who commanded U.S. forces in Vietnam] said it best. After he realized a horrible thing had happened at My Lai, he commented that of all the massacres in Vietnam, nothing matched what happened at My Lai — that My Lai was one of the most intimate, personal, in your face kind of killings that he had ever seen. So I think you can say that My Lai was one of many massacres, but probably the worst individual instance.

You were able to interview Larry Colburn — one of the helicopter crewmen who intervened to essentially stop the massacre, actively rescued wounded Vietnamese, and later spoke out about the events — before he passed away in 2016 [the other two died in 1968 and 2006, respectively]. What did you learn from him?

Howard Jones

Larry was absolutely phenomenal. He gave the best descriptions one can imagine of what happened that day and I think he was one of the most passionate people I've ever talked with about what should be done and not be done in battle. He and the other two crewmen were not pacifists by any means, but they knew that you don't slaughter civilians.

In the 1990s, Colburn and Hugh Thompson [the pilot] visited My Lai and had a number of Vietnamese come up to them and say, "I was one of the survivors, thank you." A young Vietnamese man came over with a wife and child and said that on that day, he was the young boy that the third airman, Glenn Andreotta [killed in combat three weeks after My Lai], had pulled out of a ditch where he was left to die and taken to safety with the help of Colburn.

All three crewmen were awarded Soldier's Medals for bravery in a non-combat situation in 1998 [posthumously for Andreotta] in a big ceremony at the Vietnam Memorial Wall, and Thompson and Colburn were often invited later on to speak at the service academies. But over the years they had been persecuted, intimidated, and blackballed. They'd walk into the mess hall and everyone would get up and leave because they thought the three airmen had been aiding and abetting the enemy at My Lai.

Thompson ended up in multiple marriages and was stress-torn all the way. Colburn said he was able to talk with Thompson a little bit the day before he died. He believed that Thompson died a morally broken man. He had done what was right in the most horrific of circumstances and this is what happened to him. Eventual recognition of their heroism had come at a heavy price that included telephoned death threats and dead animals left on the doorstep of Thompson's house. Once he died, Colburn received the same kind of threats up to the time he died. People just wouldn't let it go.

With the contrast between soldiers like Colburn and Thompson versus those who participated in the massacre, how do you think Vietnamese survivors now view Americans overall?

One of the survivors I interviewed was Pham Thanh Cong, who’s now director of the museum at My Lai. He said that the Vietnamese are very forgiving people. In August 2009, William Calley came forward for the first time and he was paraded around by all the newspapers as having apologized. I think that narrative is a gross error. The man never really apologized. The way I define it, if you are really going to apologize, you have a change of heart, are really contrite, admit you did wrong, and say you’re responsible for what happened. At his defense in his trial, he argued that he was just following orders, that war is the culprit. Then he said the same thing in Columbus, Georgia when he came public in 2009 — that he was following orders. He has never accepted responsibility for what he did at My Lai.

Pham Thanh Cong said he did not regard this as an apology. A couple other survivors who had lost relatives said the same thing — that this was no apology. They all said Calley needs to come to My Lai and apologize, and we will forgive him. We want to put this behind us. This is the kind of heart they have shown.

But that's not the attitude of all the survivors by any means. One survivor I cover in the last part of my book was a young woman at the time of the massacre. She had children, parents — all of them killed. And she says, "I hate the Americans. I still do. They destroyed my life." So there is a broad range of reaction, but, I think, a large number of Vietnamese are ready to put that day behind them.

How well known and understood do you think the events of My Lai are today in America?

When I would mention My Lai to friends and relatives, they would say, "Oh yeah, that was something in Vietnam, wasn't it? A battle in Vietnam?" They'd know something about it. Some know a little bit about there being a massacre. No feature movies have been made about that day. Several attempts haven't worked out for whatever reason. Movies, of course, must have some kind of redemptive factor in order to appeal to a wide audience. Yet I see some measure of redemption in the way the helicopter crew reacted — that in the midst of these mass murders, there were some American soldiers who had character, who knew the difference between right and wrong, and who actually tried to stop the carnage.

Do you think the reason there hasn’t been a movie is that Americans don’t want to remember this?

I think that's right. I think that's what the producers and directors are afraid of — that it’ll bomb at the box office. You’ll have the image of going to see a movie in which the slaughter of defenseless Vietnamese civilians is going to be drummed into you over and over. And people will think, “I don’t want to see that.” I think to make a movie about My Lai, it would have to be really carefully done.

What do you think are the biggest legacies of My Lai?

I think My Lai was pivotal in helping turn the corner against the American involvement in Vietnam. Here was the irony of it all: When Americans learned that Calley had been sentenced to prison for life, they became incensed all across the country. Those who agreed with the sentence were drowned out. Most people seemed to think he was a young boy who was trained to kill the enemy and that's all he did. He was punished for doing his duty and that was wrong — he was made a scapegoat for those above him who were more responsible than he was for what happened. There were songs written and every kind of honorable thing you could imagine exalting Calley.

President Nixon saw an opportunity for political gain and public support from supporting Calley. He told his advisors on the day of Calley’s sentence that he was going to commute him. Nixon hadn't seen any transcripts, and he hadn't heard anything specific or studied the case. He had made up his mind that he was going to free Calley.

The vast group of Americans on the right felt that Calley was being railroaded and that we've got to pull out of Vietnam because those in charge were not going to let us win the war. Then there was the other side, the left, saying that My Lai showed what the war was really like: cruel and unwinnable. We've got to end it. So you had this strange coalition of left and right coming together on one thing: get out of Vietnam.

The My Lai Massacre had long-lasting effects on the military too. As the Army started Operation Desert Storm in January 1991, one of the commanders told his men, "No My Lais in this division — do you hear me?” And later in the 1990s, the commemoration written about Hugh Thompson's award for non-combat bravery was highlighted in a box in the Army’s Field Manual, so every soldier will know the importance of My Lai.